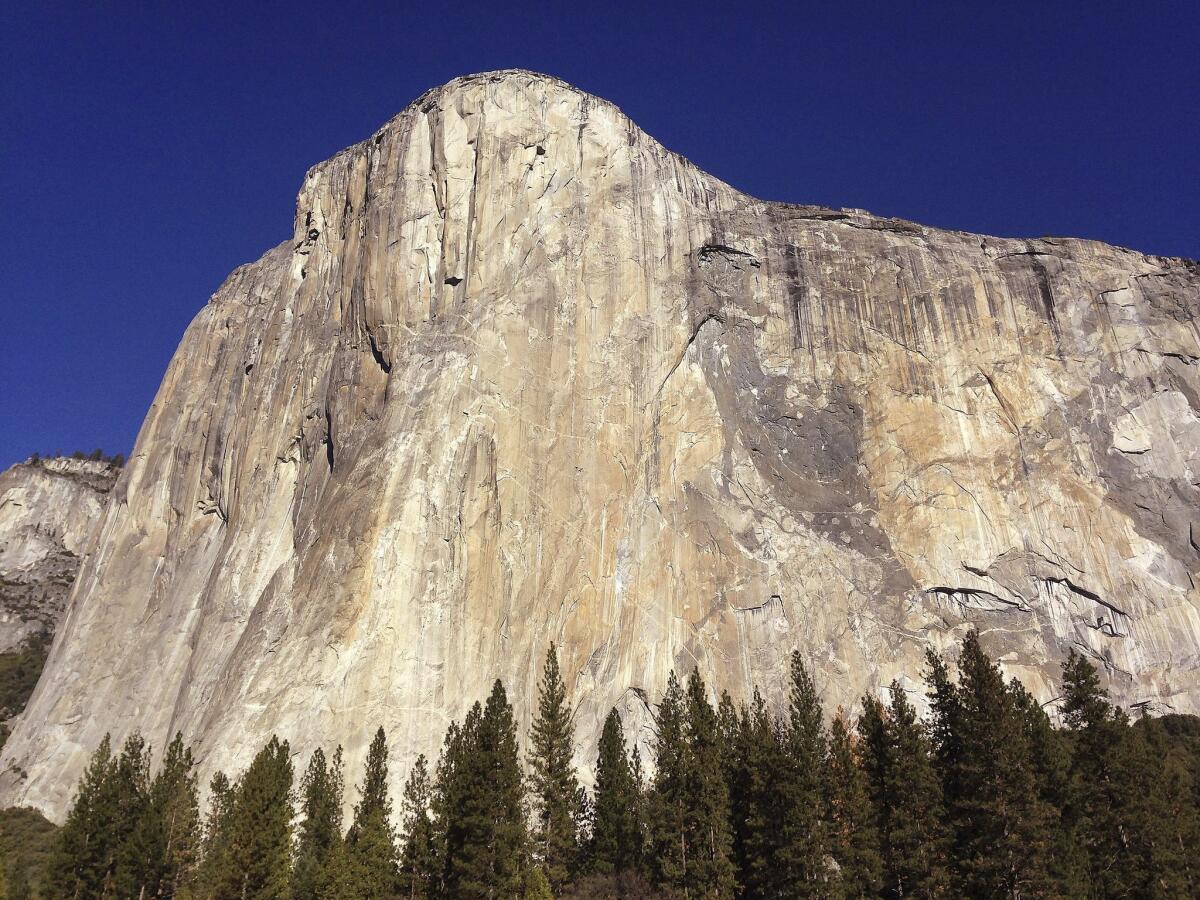

Column: The corporate grab behind the Yosemite Park trademark clash

El Capitan in Yosemite National Park. Or is it “Yosemite National Park, brought to you by Delaware North”?

If you’re a lover of U.S. national parks in general and Yosemite National Park in particular, you’ve probably been moved to outrage over reports that a New York corporation has claimed the trademark rights to several names associated with the park.

These include the historic Ahwahnee Hotel, Curry Village, and conceivably “Yosemite National Park” itself. As a response to a pending lawsuit over the issue, the National Park Service will erase some of the disputed names as of March 1; the Ahwahnee will become the Majestic Yosemite Hotel and Curry Village will be known as Half Dome Village. The park’s name will stay the same...for now.

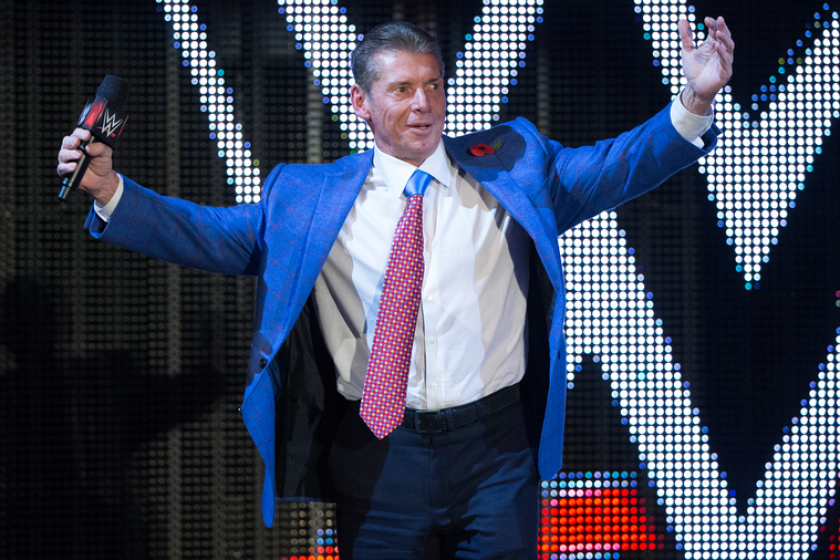

We’re not threatening to keep the names, but we are entitled to fair value.

— Dan Jensen of Delaware North

There are two important facts to keep in mind as this dispute unfolds between the government and Delaware North Cos., which operated the hotels and concessions at the park through a subsidiary since 1993 but lost the contract to rival Aramark last year, for a 15-year term starting March 1.

First: Delaware North isn’t really claiming to have trademarked “Yosemite National Park” for all purposes. It only claims to own the trademark to the extent it appears on coffee mugs, T-shirts and some other gewgaws sold in gift shops. What’s really at stake isn’t the ownership of the names and trademarks themselves, but how much they’re worth and how much Delaware North should be paid for them in the contract handoff.

“We’re not threatening to keep the names,” says Dan Jensen, a longtime park executive whose tenure at Yosemite lasted 23 years and who is now a consultant to Delaware North, “but we are entitled to fair value.”

He also says that the National Park Service had no cause to start changing the disputed names, an act that itself is trampling over park traditions. Indeed, the firm says it’s willing to allow the Park Service free use of all the trademarks at issue until the legal fight is settled.

Second: The government paints Delaware North as a grasping corporation that’s trying to hold up the taxpayers for millions of dollars it doesn’t deserve.

The dispute over the names therefore is part of a broader legal fight, though not one that necessarily makes either the company or the government look good.

In its reply to the company’s lawsuit, the National Park Service says Delaware North has “apparently embarked on a business model whereby it collects trademarks to the names of iconic property owned by the United States.” It cites its application to trademark “Space Shuttle Atlantis” in connection with its concession at the Kennedy Space Center.

According to the federal trademark database, the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office granted that trademark last year, which raises the question: Why is the USPTO so free and easy with trademarks of national assets?

As the government states, the USPTO initially rejected Delaware North’s applications to register several trademarks associated with the park, including the park name. Its reasoning was that the public associates those names with the National Park Service, not the company. What the government doesn’t say--perhaps out of embarrassment--is that the trademark office eventually approved some of the applications, though typically of name-and-logo combinations, not of the names themselves.

Here’s how the Yosemite conflict happened.

The story begins with Curry Co., which in one form or another had run facilities at the park since 1899. By 1993, Curry was owned by MCA, which was owned by Matsushita of Japan. Then-Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan declared that a foreign-owned firm couldn’t run concessions at a national park. Delaware North, which operates at numerous sports stadiums and other venues across the country, took over the rights at Yosemite by buying Curry Co.’s stock, paying MCA about $61.5 million--about $115 million in today’s money--for tangible and intangible assets, including trademarks.

Delaware North says that the original contract never spelled out in detail what it owned or its value. Subsequent federal legislation governing concessions on federal property only served to muddy the waters. It was understood from the inception of the contract that the real property in the park, including the hotel, belonged to the government, and that the intangibles would have to be transferred to any new concessionaire at “fair value.”

There’s the rub. There’s no detailed list of all the intangible property, and no agreed-on method of determining its fair value. Delaware North says it’s all worth $51.2 million, based on an appraisal it commissioned covering 32 trademarks, Internet domain names, and other assets. The government says these assets are worth $3.5 million.

The government says Delaware North has consistently tried to high-ball its estimate of what it’s owed in the property transfer to Aramark. Its $51.2-million estimate was submitted to the government “without any explanation or documentary support,” according to the government’s reply to the company lawsuit.

The government contends that the firm’s appraisal ignores the “unique paradigm of a concession within a national park”--that it’s not the trademark that draws visitors and creates value, but the park and its surroundings, which are government property.

This is certainly true. The names “Ahwahnee Hotel,” “Curry Village” and “Yosemite National Park” have virtually no value separated from the park itself. Delaware North theoretically could open a hotel just outside the Yosemite boundaries and call it the “Ahwahnee,” but that would only devalue the name, not exploit it.

The issues in this fight are fundamentally simple. First, what’s the reasonable value of trademarks, websites, mailing lists and other intellectual property associated with Yosemite National Park? On a guess, it’s somewhere between $3.5 million and $51.2 million.

Second, how could the government be dumb enough to allow any confusion to exist about what belongs to the public and what belongs to a concession contractor operating on public land? The careless approach to the national patrimony has led not only to the Yosemite dispute but the Cliven Bundy standoff and the comic opera goings on by the so-called militia at the Malheur Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. If federal administrators won’t enforce the public’s rights on all these lands, who will?

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see our Facebook page, or email [email protected].

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.