Column: Saudi Arabia is threatening to sell $750 billion in U.S. assets. Talk about an empty threat.

The latest shudder in the long-running international drama known as U.S.-Saudi Arabian relations occurred late last week, with a report that the Saudi government had threatened economic retaliation over a bill in Congress that could make it liable for damages from the 9/11 attacks.

Specifically, the report in the New York Times said the Saudis had said they might sell "up to $750 billion in treasury securities and other assets in the United States" if the bill passes.

The report sparked instantaneous hand-wringing and blustering across the social media fever-scape. A sudden sale of $750 billion in Treasury securities, it was said, could crater the bond market, leading to price declines of 50%-60%. The Saudis were out of line in interfering with the U.S. legislative process, it was said. And aren't they just trying to hide their complicity in the attacks.

"Few Americans would take the threat as anything short of a slap in the face of the victims of 9/11 and the country as a whole," declared George Washington University law professor Jonathan Turley, whose number is in the Rolodexes of cable TV bookers Washington, D.C.-wide; expect to see him on the air shortly.

Can we all take a deep breath? This isn't much of a threat. If the Saudis followed through, they would most likely be the losers.

Few Americans would take the threat as anything short of a slap in the face of the victims of 9/11 and the country as a whole.

— --Law professor Jonathan Turley

A few things need to be cleared up about this bill and the so-called Saudi threat. First, the bill doesn't hold Saudi Arabia responsible for 9/11 or declare it liable for damages from the attacks. It deals with the immunity enjoyed by foreign sovereign governments in U.S. courts, removing it in cases where foreign governments are found responsible for attacks that kill Americans on American soil. The bill passed the Senate Judiciary Committee in January with a bipartisan vote. But since the Obama administration has been lobbying against it, the bill is likely to be vetoed even if it is passed.

Since the Saudis long have been suspected of complicity in the attacks, it's fair to say they're the prime target of the legislation. But the Saudis' immediate concern is that their U.S.-based assets could be frozen by a court for the lengthy period it would take for lawsuits for damages to make their way through the judicial system. That makes their representation about U.S. assets look a bit less like a threat than an expression of defensive strategy.

Even so, it raises two questions: Would such a sell-off be practical, and what would it do to the markets?

Let's examine the second question first.

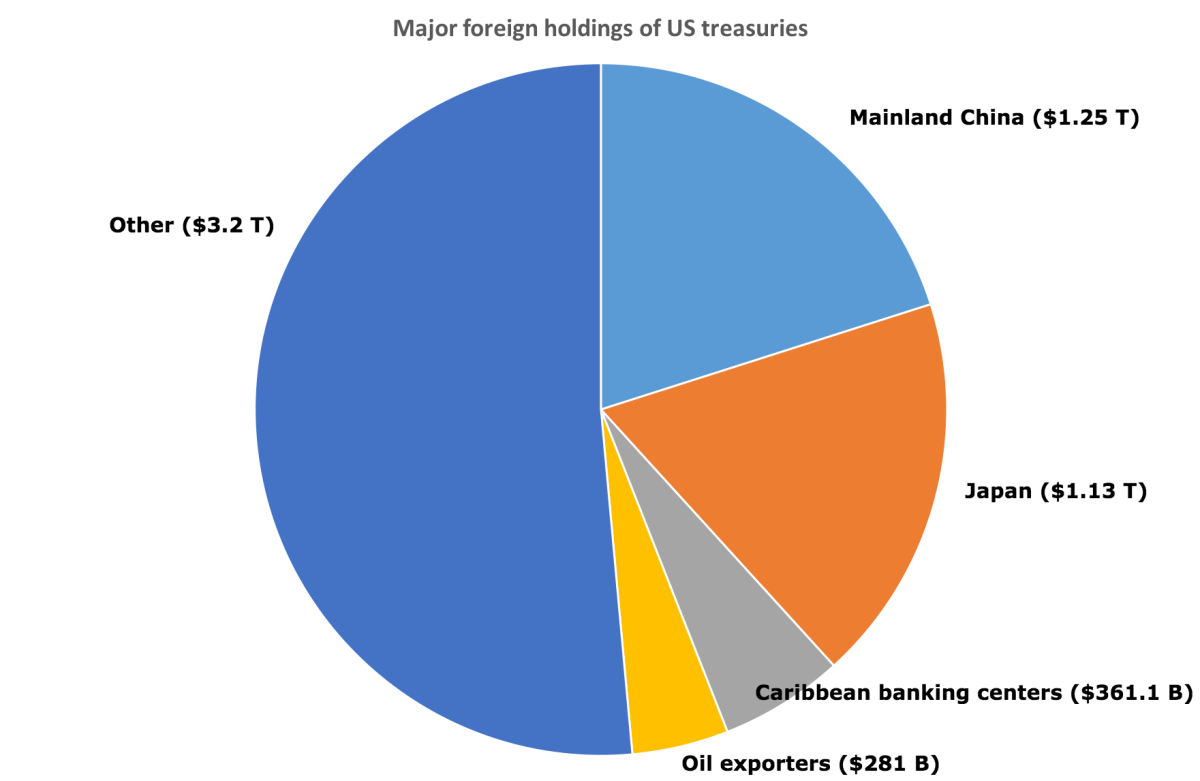

In the game of telephone invariably played by social media, the original report's careful phrasing of "up to $750 billion in treasury securities and other assets in the United States" quickly morphed into $750 billion in Treasury securities. That would be a sizable chunk of the roughly $6.2 trillion of Treasuries held in foreign hands (by the Treasury's estimate) and even of the $12.6 trillion in U.S. government debt estimated to be in public hands (that is, not held by government agencies).

But it doesn't appear that the Saudis hold anywhere near that sum in U.S. Treasuries. Although the government reports a good deal of foreign holdings of Treasuries by country, it folds Saudi holdings into a bulk category of 15 oil-exporting countries. This controversial concealment, an artifact of the 1970s oil shocks, is manifestly designed as a big diplomatic favor to the Saudi government. It's long overdue for revision, but successive administrations have chosen to let it be.

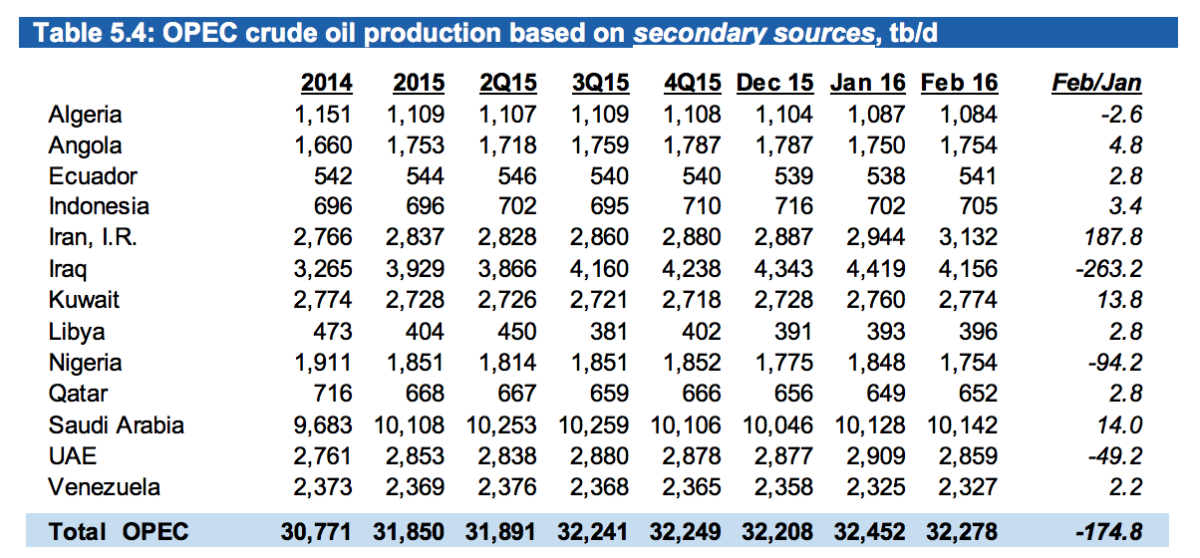

In any case, the oil-exporter category amounts to only $281 billion, according to the Treasury. It's swamped by the largest holdings, China ($1.25 trillion) and Japan ($1.13 trillion). Obviously, Saudi Arabia's holdings must be less than $281 billion, though how much less is almost impossible to gauge. Suffice to say that Saudi oil production amounts to roughly a third of all OPEC production, so its holdings of U.S. Treasuries are likely to represent at least a large plurality the oil-exporters category, if not a majority.

It's proper to note that the figure of $750 billion in U.S. assets may itself be a gross overstatement. Saudi government investments are managed through its SAMA sovereign wealth fund, which was worth about $750 billion in 2014, but has declined to less than $685 billion since then, in part because the oil-price slump has forced the Saudis to liquidate some of their holdings for cash. Of that, about $423 billion were in overseas securities, including U.S. Treasuries, as of November.

Not all those investments are in the U.S. or in dollar-denominated assets. SAMA's holdings include much more than government securities, U.S. or otherwise. About 20% of its portfolio is estimated to be in global equities. The fund also holds real estate, including refineries.

See the most-read stories this hour >>

Whatever the Saudis' holdings, how much could they liquidate and how fast? The answers probably are not so much and not very quickly. Liquidating their entire holdings of U.S. Treasuries would have to be done over time, and if the sales began to move market prices--not necessarily the case--that would have an effect on the Saudis' own portfolio. As Tim Worstall observes at Forbes.com, sales on this scale could be easily absorbed by the bond market; even if they appeared to have a price effect, the Federal Reserve could step in and compensate with purchases of its own.

Another question is what would Saudi Arabia do with the money? If the government really is fearful of dollar-denominated assets becoming subject to a freeze, they would have to be moved into another currency. That entails a whole new category of risk, for the dollar is still regarded as the most stable currency in the world.

The bottom line is that selling assets on the scale that the Saudis have reportedly talked about would be extremely costly, possibly more for the Saudis than for anyone else. The talk about dumping U.S. investments begins to look less like a threat than a plea born of desperation. The message is, please, please don't make us do this.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik's blog.

MORE FROM MICHAEL HILTZIK

Watch the U.S. age before your eyes in this amazing animated graphic

Time's debt scare cover story is a journalistic — and economic — train wreck

How a Wharton professor grossly inflates Social Security's deficit to argue for a 'fix'

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.