Column: New Obamacare surprise: New customers look just like average Americans

Blue Cross/Blue Shield, which is the largest player in the individual exchange market under the Affordable Care Act, has taken a close look at its enrolled population since the exchanges opened for business on Jan. 1, 2014. For some reason the Blues seem to be surprised at this finding:

Members who enrolled in 2014 and 2015 "have higher rates of certain diseases such as hypertension, diabetes, depression, coronary artery disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and Hepatitis C than individuals who already had BCBS individual coverage....received significantly more medical services in their first year of coverage, on average..., (and) used more medical services across all sites of care—including inpatient hospital admissions, outpatient visits, medical professional services, prescriptions filled and emergency room visits."

After years of being discriminated against, Americans with preexisting conditions are no longer locked out of coverage because of a health condition like asthma or diabetes.

— --Benjamin Wakana, HHS

Here's the money quote: "Medical costs associated with caring for the new individual market enrollees were, on average, 19 percent higher than employer-based group members in 2014 and 22 percent higher in 2015."

The Blues are implying that these costs are higher than they expected, but the report actually tells a very different story: It demonstrates exactly why the Affordable Care Act was a necessity.

The reason that new enrollees tend to be sicker than the previous pool of patients in the individual market, and consequently are using more services and costing insurers more, is that sick people were systematically excluded from the individual insurance market prior to 2014. The mechanism was exclusions for pre-existing conditions, which were outlawed by the ACA.

Federal healthcare officials were quick to point that out Wednesday, after the report's release. "After years of being discriminated against, Americans with preexisting conditions are no longer locked out of coverage because of a health condition like asthma or diabetes," said Benjamin Wakana, a spokesman for the Dept. of Health and Human Services. "It’s no surprise that people who newly gained access to coverage under the Affordable Care Act needed health care; that’s why they were locked out of coverage before."

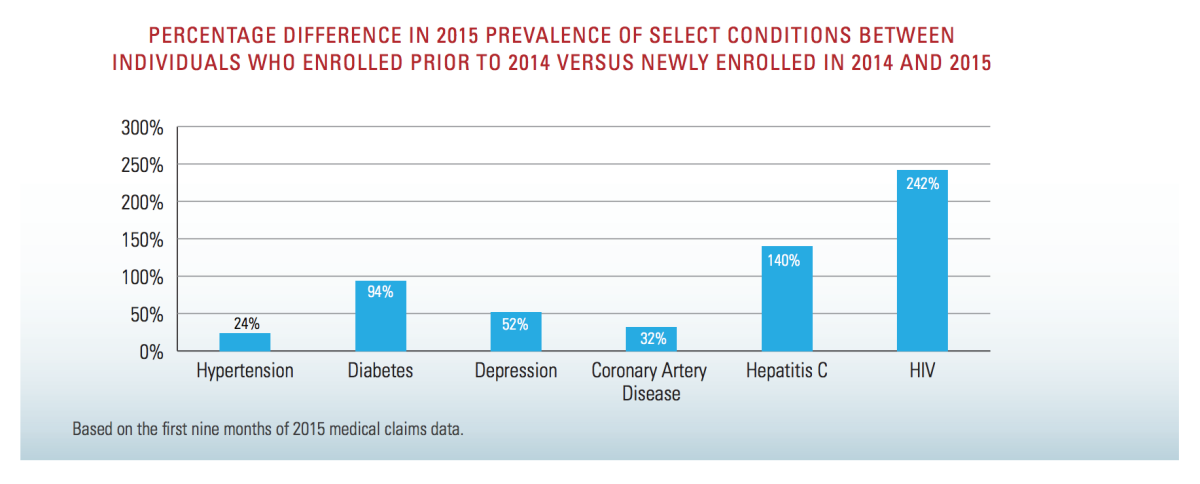

That's demonstrated graphically by the Blues' report. It shows, for example, that post-ACA enrollees are 242% more likely than pre-ACA enrollees to suffer from HIV, 140% more likely to carry a hepatitis C infection, and 94% more likely to have diabetes. (See chart below.)

Of course, these are exactly the types of patient who had almost no prayer of obtaining health insurance in the individual market before. The moment an applicant disclosed that he or she was HIV-positive, the doors would slam shut. Now they're open.

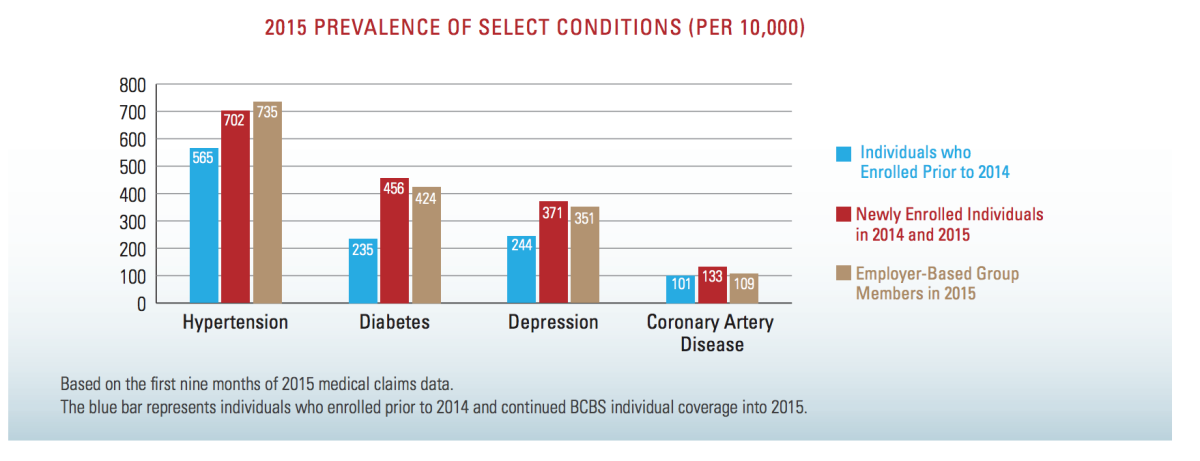

The report underscores this point in another way. While the post-ACA enrollees show materially higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, depression, and coronary disease than the pre-ACA cohort (see chart below) they resemble the population of employer-insured customers fairly closely.

As Kevin Drum of Mother Jones observes, that shouldn't be surprising, because employer plans, like the ACA plans, traditionally "take all comers," healthy or ill--they haven't been permitted to exclude any individual, as long as the applicant meets the sponsoring employer's standards (typically hours worked or job classification).

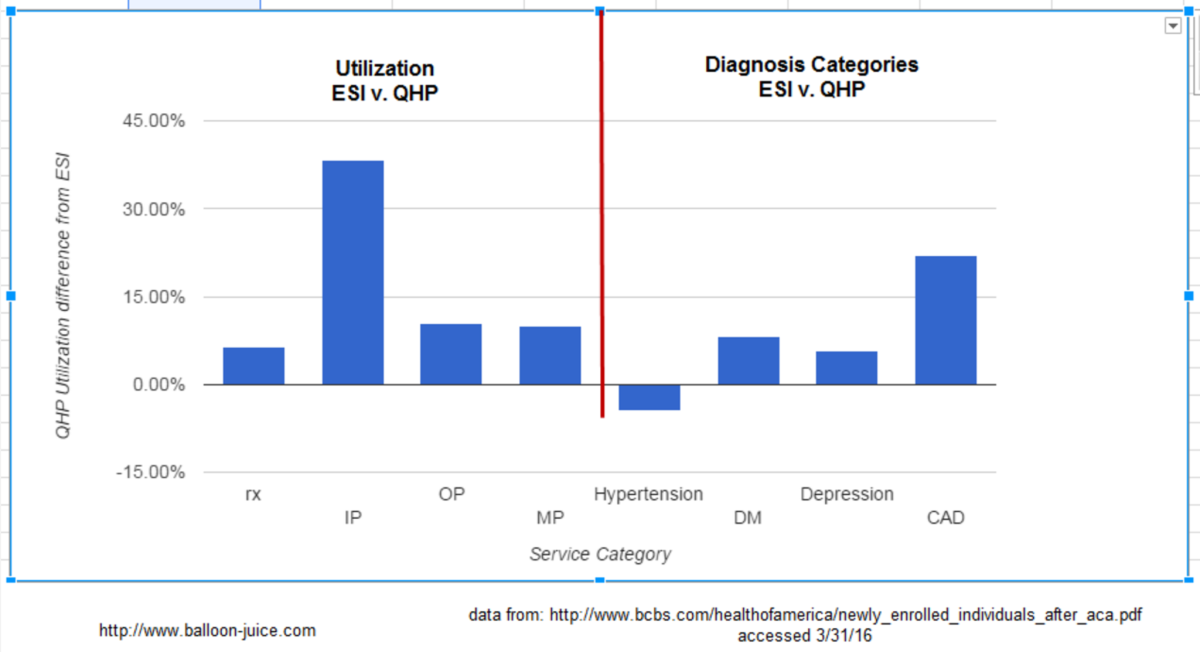

[UPDATE: Richard Mayhew, the health insurance authority at Balloon-juice.com, takes strong issue with the notion that the costs of the post-ACA individual market enrollees resemble those of the employer-sponsored customer pool. On the contrary, he says, the differences are "very significant." Mayhew's issue is with Drum's analysis, but since ours is similar we'll take his criticism on board, too.

[Mayhew observes via the accompanying chart that utilization rates by new ACA enrollees are higher than those in the employer-sponsored pool by as much as 40%, and in several categories approach or exceed 10%. "Over millions of covered lives, differences of 10% of utilization for outpatient and medical professional claims is operationally significant," he writes. "Speaking as someone who does this for a living, we celebrate as a major success when an initiative drives down inpatient spend and utilization by 2%. 40% differential is massive." He says the differential makes sense, in part because full-time employment carrying insurance benefits is itself a screen for health: "If someone is sick with diabetes, depression and coronary artery disease, they are less likely to be working 30 hours per week."

[A couple of points in response: HHS officials observe that the BCBS survey broke out the costs of newly-enrolled individual members and compared them both to the costs of pre-ACA enrollees and to employer-plan members, but didn't show the costs of the combined pre- and post-ACA individual enrollees--that is, the entire pool of healthier and sicker individual members. It's reasonable to assume that taken together, this pool will look even more like the employer-sponsored group. It's also worth repeating that newly-insured people are likely to have elevated needs after years without insurance, but as they obtain treatment, their costs should decline.]

One predictable outcome of this change in the individual market was that some pre-ACA enrollees--especially the healthiest--would see their costs rise, as their insurance pools accommodated the one-time excluded. their old insurance rates were the product of now-outlawed cherry-picking. The other was that millions more people would have access to coverage.

Both eventualities have come to pass; the customers facing the largest price increases tend to be the low-risk customers who constituted a huge share of the cherry-picked customer base. But 9.1 million Americans are now insured through the exchanges and receive tax subsidies to help pay for coverage. Another 9 million or so are on the exchanges, but unsubsidized. About 11 million are receiving coverage via expanded Medicaid eligibility.

Some healthcare experts, including a few at HHS, are wondering whether the Blues timed their report to set the stage for the round of premium requests that insurers will be filing in coming weeks for their 2017 plans. The concern is that they'll be pointing to the report's findings about the higher cost of insuring ACA enrollees to justify steep increases in their requested rates. As Larry Levitt of Kaiser Family Foundation tweeted, "This BCBS study is likely building the case for bigger hikes."

But those rate requests will need to be viewed in multiple contexts. For one thing, the larger the request, the greater the chance that the insurer miscalculated its costs in the first years of the ACA exchanges, whether out of incompetence, inexperience, or deliberately to grab market share. In such cases, they may be trying to get back money they left on the table previously. Also, the initial rate requests typically are just opening bids, subject to oversight by state insurance regulators. And the rates sought don't necessarily resemble those paid by customers, since more than 80% of customers in the market are eligible for tax subsidies.

Uncertainties about costs in the new individual market were expected; that's why the law incorporated three years of risk adjustments, through which carriers that ended up with above-average risks were compensated, and those with below-average risk pools had to give up some of their gains. In 2014, nearly $8 billion in reinsurance payments were transferred to over-risked insurers for those with lower risks than the average under this program, according to government figures.

The Blues were among the biggest recipients, the government says, suggesting that their insurance pools were somewhat sicker than the national average.

This system worked well, by the way, until Congress threw in a monkey wrench by limiting the administration's ability to make the transfers. The architect of this entirely unnecessary glitch was Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.), who used it to burnish his credentials as a GOP presidential contender. To no avail, obviously.

What are the biggest lessons to be drawn from the Blues' report: The Affordable Care Act was necessary, and it's working.

Keep up to date with Michael Hiltzik. Follow @hiltzikm on Twitter, see his Facebook page, or email [email protected].

Return to Michael Hiltzik's blog.

UPDATES:

6:41 a.m., Mar. 31: This post has been updated with the analysis by Richard Mayhew of balloon-juice.com.

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.