‘The Holy or the Broken’ tracks a song’s slow build to classic

- Share via

The Holy or the Broken

Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah”

Alan Light

Atria: 272 pp., $25

There’s a great scene in Penelope Spheeris’ 1992 film “Wayne’s World” — find it on YouTube under the title “May i help you riff” — in which an impatient guitar-store employee prevents Wayne from plucking out the opening arpeggios of “Stairway to Heaven” by Led Zeppelin. Pointing with great urgency, the guy directs Wayne’s attention to a sign hung on the store’s wall: “NO STAIRWAY TO HEAVEN,” it reads.

In Alan Light’s new book about the music of Leonard Cohen, the singer-songwriter Brandi Carlile describes another such printed prohibition, this one taped to a soundboard at L.A.’s Hotel Café, where Carlile says performers are enjoined from doing a tune that in recent years has become nearly as ubiquitous as Led Zeppelin’s rock-canonical classic. The sign’s beseeching request? “PLEASE DO NOT PLAY ‘HALLELUJAH.’”

Just how Cohen’s song — released to little fanfare in 1984, and still an obscurity at the time of “Wayne’s World” — came to its current position is the story Light takes up in “The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley & the Unlikely Ascent of ‘Hallelujah.’” It’s a deeply researched mixture of critical analysis and cultural archaeology from a veteran music journalist who’s topped mastheads at Vibe and Spin, and it comes at a moment of increased interest in Cohen, the Canadian raconteur known for songs like “Suzanne” and “Bird on the Wire.”

In January he put out “Old Ideas,” his first new studio album since 2004, and an acclaimed biography by Sylvie Simmons arrived on shelves in September. And last week Cohen concluded a lengthy world tour with two arena concerts in New York. Of his show at the Nokia Theatre in L.A. last month, Times pop critic Randall Roberts wrote, he “confirmed [his songs] to be as durable as the ages.”

That durability is key in Light’s account of “Hallelujah,” which first appeared on an album, “Various Positions,” that Cohen’s label rejected for being a noncommercial “disaster,” as the record’s producer tells Light. Yet the song — a wry reflection on the intersection of sex and religion — slowly found favor among other artists; Bob Dylan performed it on stage and John Cale covered it for a 1991 tribute album.

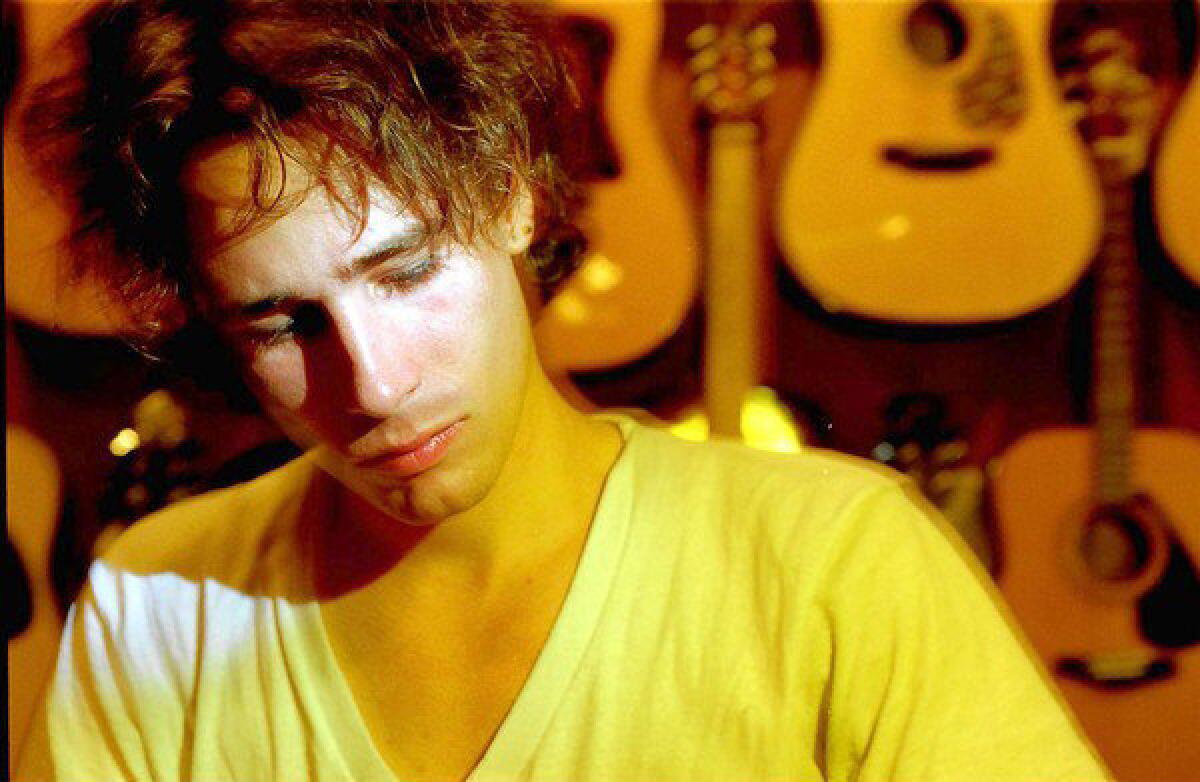

And then Jeff Buckley, the ill-fated son of the ill-fated folkie Tim Buckley, discovered the song and included a searingly gorgeous version on his 1994 debut, “Grace.”

That’s where Light’s book gets interesting, as the author charts in ample (if occasionally lumpy) detail the way Buckley’s imprimatur drove “Hallelujah” outward into the indiscriminate scrum of mainstream pop culture — into the animated movie “Shrek;” into television coverage of the 9/11 attacks; into the standard repertoire of singing competitions such as “American Idol” and “The X Factor.”

Drawing on countless interviews with musicians and industry insiders — including Bono, Regina Spektor and, crucially, a cast member from “One Tree Hill” — Light argues that Cohen’s song provides “a shortcut to feelings of contemplation, loss, solitude.”

Yet he points out its differences from similar totems, such as John Lennon’s “Imagine,” for example, or “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon & Garfunkel. Because “Hallelujah” found renown through a series of disparate covers, Light writes, it “isn’t fixed and formalized” in the collective consciousness and can therefore withstand “multiple modifications, possibly resulting in a change of its emphasis, but not its essence.”

His proposition seems to be a kind of rebuke to the warning Carlile recalls receiving at the Hotel Café: You can’t be denied access to a song you make your own.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.