Why ‘1984’ is still relevant today — but not for the reason you may expect

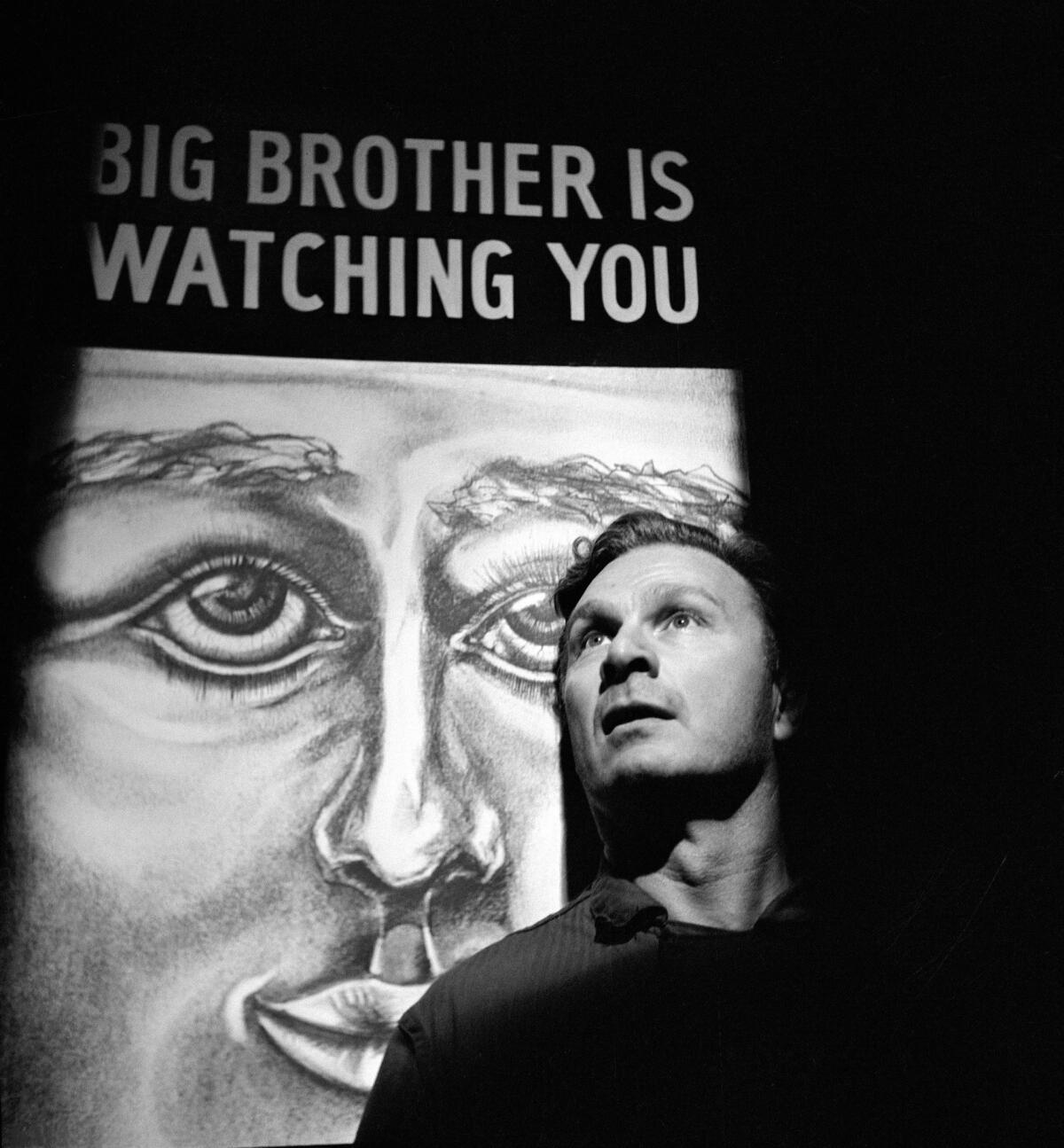

Of course Big Brother isn’t just watching us anymore — he’s listening to our cell phone and FaceTime conversations, friending us on Facebook, following us on Instagram (just as we are often following Him). He’s introducing us to our next partner or spouse on dating and “hook-up” apps, bombarding us with spurious and inaccurate information through jargon and euphemism (“border control” as a code for family separation, or “climate change” as a substitute for “climate collapse”), and instructing us — even from as far away as other continents – about who we should vote for and, more important, who we shouldn’t. Big Brother is no longer simply a set of shadowy, avuncular, half-smiling eyes on living-room posters and street-side billboards; he now reserves a virtual space at all our family gatherings, and tells us what to do and buy long before we had the inclination to do or buy anything.

Good ol’ Big Brother. He got a lot of bad press over the decades — but that was before we found out he was already one of us.

While times have changed, the things that worried George Orwell haven’t changed at all. The most important thing to know about “future-thinking” “utopian” and/or “dystopian” novels is that they are never really about the future at all; instead these novels are about the world that surrounded the author. That is why one of the unproven rumors about “1984” — as explored in Dorian Lynskey’s “The Ministry of Truth,” a respectful and intelligent “biography” of a novel — is that the title was merely a transposition of its publication date, 1948. In other words, in Orwell’s eyes, “1984” was well already well-established four decades before it got here.

For Orwell, the horror of totalitarianism was not that someone would impose it on you, but rather that you might be all-too-prepared to submit.

— Scott Bradfield

Born Eric Arthur Blair in 1903 — he only adopted the now iconic professional pseudonym of Orwell in 1933 — the writer was the son of politically mixed parents: His half-French mother “mixed with suffragettes and Fabians,” and his father was a relatively bland mid-level civil servant. Orwell went on to become a consistently radical critic of his world who always appreciated the conventional pleasures of middle-class and working-class life; his novels and essays are thick with appreciations for everything from drinking tea and smoking cigarettes to the novels of Dickens and Kipling — and the “naughty” seaside postcards of Donald McGill. After skidding along unillustriously as a “scholarship” boy at Eton College, he joined the Imperial Police in Burma, where he quickly learned what it felt like to wear a uniform — and how it could make you think and feel things you might consider repugnant when you weren’t wearing it. (Check out his great personal essays about that period, “A Hanging” or “Shooting an Elephant” — for Orwell, the horror of totalitarianism was not that someone would impose it on you, but rather that you might be all-too-prepared to submit.) Eventually, he went to London, where he wrote productively for the left-wing press — while never missing an opportunity to criticize its failures – and after a brief adventure fighting Franco in the Spanish Civil War, secured a full-time job working for the BBC, a monolithically imposing cultural force that Orwell later satirized as “The Ministry of Truth.”

In many ways, Orwell’s genius was best exemplified by his essays and journalism — and the success of his most famous novels (it may be impossible to avoid either “1984” or “Animal Farm” in most high school curricula) has often obscured the impact of the things he said. For example, he wasn’t — as students are often mis-taught — concerned simply with the oppressive forces of Stalin or “socialism,” but rather with almost every “ism” that manipulated truth through the misuse of language and political propaganda. Even more confusing, “1984’s” message has often been appropriated by the very types of organizations that Orwell despised, thus becoming, as Lynskey writes, “a book that almost any political faction could claim.” It has been held up as a warning about the perils of imperialism, capitalism, socialism and fascism; it has been lauded by both the John Birch Society — who used the numbers 1-9-8-4 as the last four digits of its phone number — and the Black Panthers, who taught Orwell in their Oakland Community School.

The novel has inspired at least one mediocre Hollywood production (starring the weirdly miscast Edmund O’Brien in 1956), several BBC adaptations, and the more interesting Michael Redford film starring John Hurt and released, appropriately enough, in 1984. And it has gone on to live a life far beyond its title in Terry Gilliam’s comic nightmare 1985 film “Brazil” — “I hadn’t read 1984,” Gilliam said, “but we all know what it is” — and as a successful product-branding Ridley Scott television commercial for Apple in 1983, wherein a woman in a tank-top saves the world from conformity with a hammer. The word “1984” has even entered our own contemporary version of “Newspeak” as a shorthand term that simply means — “bad future.” And who can disagree with the idea that we should all avoid living in it?

Orwell’s “1984” has been applauded by everyone from Noam Chomsky to Lee Harvey Oswald — and regarded suspiciously by Stalinists and J. Edgar Hoover and Christopher Hitchens alike — and the novel has not lost any of its power today. Many things have changed since Orwell wrote this terrifying, beautifully written and, yes, extremely funny book. But Orwell’s world where “War is Peace,” “Freedom is Slavery,” and “Ignorance is Strength” — sounding much like a cable news panel filled with angry pundits — rings truer now more than ever.

::

“The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell’s ‘1984’”

Dorian Lynskey

Doubleday; 355 pp., $28.95

Bradfield is a writer whose novels include “The History of Luminous Motion” and “Dazzle Resplendent: Adventures of a Misanthropic Dog.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.