Actual Asian poets use #WhitePenName to respond to poetry controversy

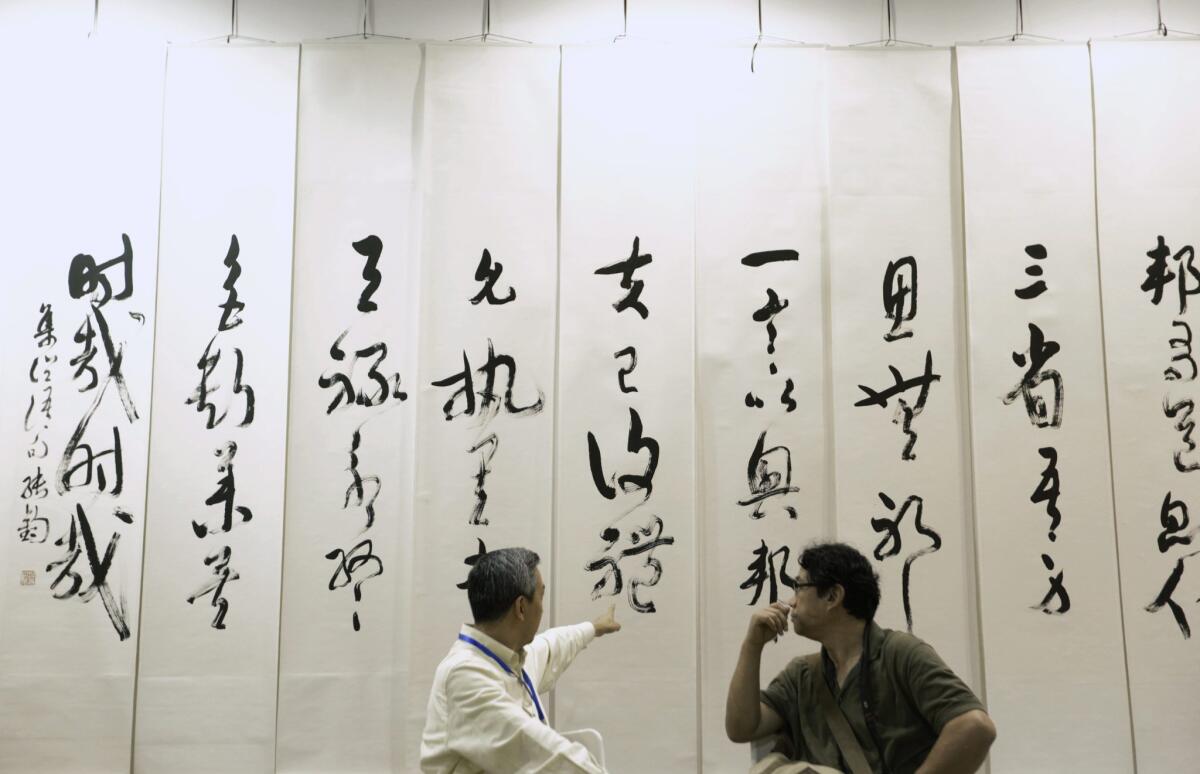

Chinese calligraphy on display at the Beijing International Art Exposition. A white American poet took a Chinese pen name to make his work more attractive to editors.

What’s more likely to get your poem published: a “white” name or a Chinese one?

The Asian American Writers’ Workshop has responded to the controversy around “Chinese” poet “Yi-Fen Chou” (actually Michael Derrick Hudson, who is white) with satire. The organization started the #WhitePenName hashtag and encouraged fellow writers of color to imagine what benefits they could get if they used a stereotypically “white” pen name.

They even created a “White Pen Name Generator.” Visit the site and you will be given your very own parody name that looks and sounds “white” (mine is “Donald Trump Reed.”)

The controversy started when Hudson, as Yi-Fen Chou, was included in the “Best American Poetry 2015” anthology, which was published this week and revealed the deception.

Hudson says he submitted the poem to 40 publications and couldn’t get accepted. But under the Chinese name “Yi-Fen Chou,” his poem was published with relative ease, finding a home after nine submissions at the literary journal Prairie Schooner and then making the cut for the anthology.

“Best American Poetry 2015” guest editor Sherman Alexie, who is Native American, explained that he was more amenable to the poem because he thought the author was Chinese. But even after he realized the true identity of the author, he ultimately decided to keep the poem in the collection, as he found it to be a good one.

In response, the literature community has exploded into debate. Some praised Alexie for his honesty, and others expressed disappointment that a “fake” Chinese American is now part of the modern American literary canon.

Alexie, who called Hudson’s usage of a Chinese pen name “colonial theft,” admitted that he was angry at himself for being fooled.

“Hudson had to have been aware of who the editor was,” writer and Louisiana State University professor Daniel Peña said via phone interview on Thursday. “He had to know that Alexie was trying to correct a years-long pattern of injustice of excluding writers of color. And he consciously tried to exploit it. I’m not sure what statement he thinks he’s making about contemporary poetry, but it’s coming from a really dark place.”

And Hudson is not the first white person to dupe audiences into believing he’s a person of color.

Angelenos may remember the story of Danny Santiago, the talented young Chicano writer who penned the prizewinning 1983 novel “Famous All Over Town,” a coming-of-age novel about a streetwise Chicano boy growing up in the East Los Angeles barrio. But Danny Santiago wasn’t actually a young Chicano, or even a Santiago; it was later revealed that he was actually Daniel James, a 73-year-old white man who had been educated in the Ivy League and blacklisted in Hollywood.

Then there’s Rachel Dolezal, the Spokane, Wash., woman whose parents say she is white, although she identifies as black; Vice has dubbed Hudson the “Rachel Dolezal of Literature.”

But there is an important difference between Hudson and his predecessors. “Famous All Over Town,” despite its deception, was still, in the late 1980s, treasured in Los Angeles high schools as an inspiring book for young people of color searching for characters with whom they could relate. And Dolezal, before the scandal, was known in her community of Spokane for her scholarship and work with the NAACP.

So whereas some of the anger against Dolezal and Santiago was tempered by the appreciation of their contributions, Hudson has earned no such benefit. He has not claimed to contribute to any causes in the Asian American community, nor is his poem focused on inspiring a shared Asian American experience.

Instead, his critics say, he merely took from the “crumbs” that minority writers have to survive on in the literary world. (He even appears to have taken the name “Yi-Fen Chou” from a woman who attended high school with him in Fort Wayne, Ind., her family tells the New York Times).

Still, Jyothi Natarajan, managing editor of the Asian American Writers’ Workshop, says that the controversy has something of a silver lining.

“We’re really happy that #ActualAsianPoet has also taken off along with the #WhitePenName tag,” she said, in reference to the hashtag that started as a joke in her office. Now, social media users are promoting the work of Asian American poets.

Peña says that after years of being underrepresented, agents are finally more willing to “take a risk” by investing in a writer of color.

For some, though, this may not be cause for celebration, but alarm. Ken Chen, executive director of Asian American Writers’ Workshop, wrote that Hudson’s actions were those of a “hysterical white man” who was envious of writers of color who were finally gaining recognition.

Alexie says Hudson used the pseudonym “as a means of subverting what he believes to be a politically correct poetry business.”

If this is the case, Hudson is not alone in his sentiments. Like those who argue against affirmative action, some seem to believe that the poetry business, as “The American Conservative” suggests, is trying to “have it both ways” by sacrificing merit for empty diversity.

Peña sees this sentiment as a wider problem in the literary community. “I think there are a lot of white writers that are freaking out about the fact that there is a digital renaissance of writers of color,” he said. “We’re finally starting to become noticed, and some people unfortunately see that as a threat.”

But in the end, Natarajan says, “If this whole controversy has helped to get people talking about and looking for actual Asian American poets, then that’s a good thing.”

Follow me @dexdigi for more on the intersection of culture and the Internet.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.