On Martin Luther King Day, remembering his largely forgotten mentor

- Share via

Every year, Americans remember the life of the man became a symbol of courage and struggle. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life has been celebrated in much great literature: My colleague Carolyn Kellogg assembled a reading list of essential books about King last year.

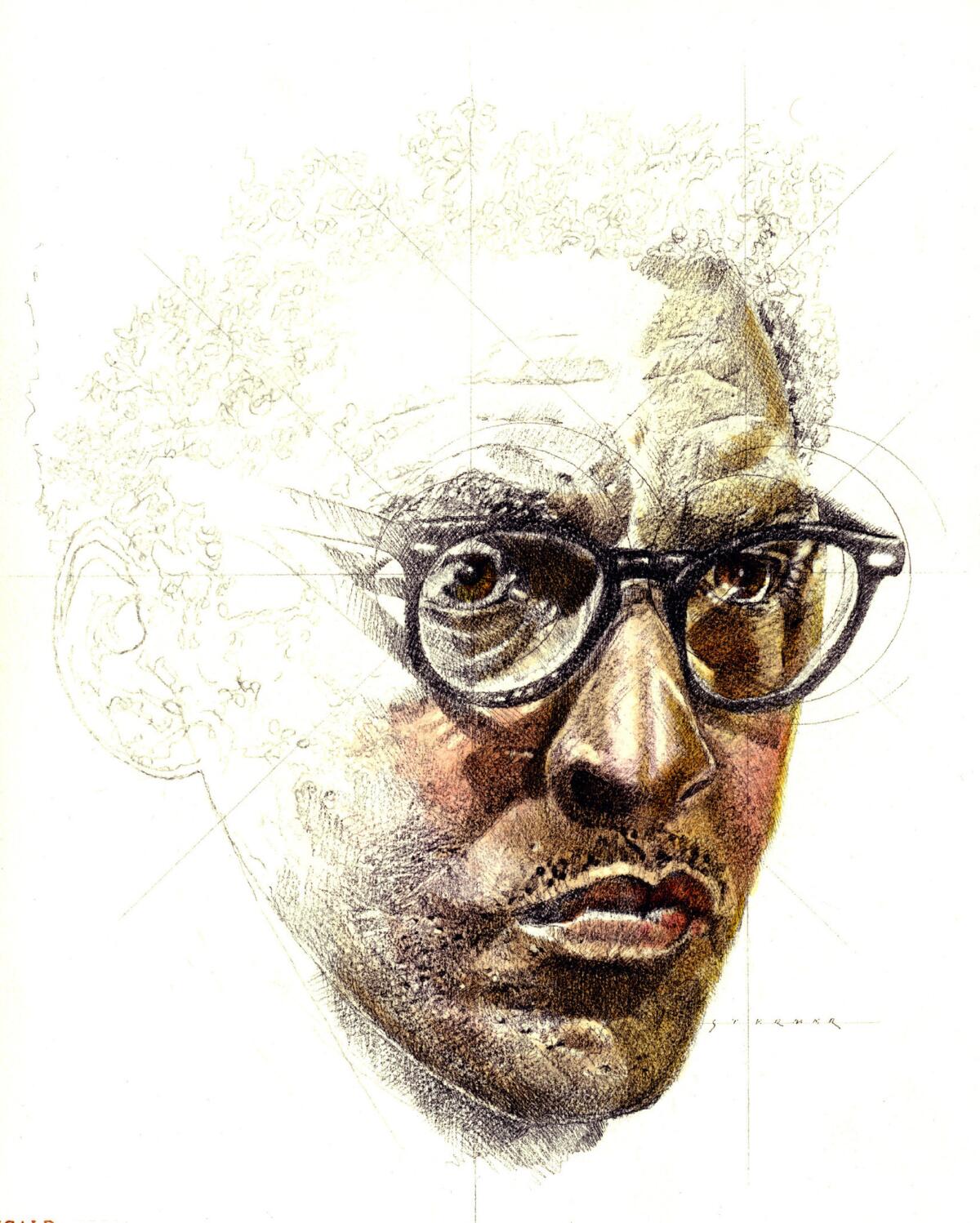

But King was inspired by an existing tradition of nonviolent resistance to injustice. One of the men who helped shape King’s ideas -- he’s often been called a leading mentor to King -- was Bayard Rustin.

Rustin’s contributions to the civil rights movement are not nearly as well-known as King’s. A recent event at Yale University celebrating his life called him “the most important civil rights leader you’ve never heard of.”

Born in 1912, Rustin was 17 years King’s senior and an early leader in the movement. It was Rustin who helped introduce King to the ideas of Gandhi: In 1948, Rustin traveled to India to meet Gandhian leaders, not long after Gandhi was assassinated. He was also the chief organizer of the 1963 March on Washington at which King delivered his famous “I Have a Dream” speech.

Rustin also happened to be gay. His eventful life and writings are the subject of half a dozen books, including the 2013 “I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin’s Life in Letters,” edited by Michael G. Long, from City Lights Books. The first entry in that wonderful collection of letters is a missive to a Quaker group that Rustin penned in 1942. Rustin’s grandmother was a Quaker, and the letter, titled “War is Wrong” in Long’s anthology, places Rustin firmly in the long tradition of American pacifism.

“I believe the greatest service we can render the men in the armed forces is to maintain our peace testimony and to expend our energies in developing a creative method of dealing non-violently with conflict,” Rustin wrote.

Rustin is also the subject of a major biography of epic length (568 pages): “Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin,” by John D’Emilio for the Free Press. In a 2003 review of “Lost Prophet” for The Times, Tom Wicker said the biography brought forth the personal tragedy of Rustin’s amazing life.

“Rustin was a charismatic leader, a lifelong pacifist, an imprisoned conscientious objector during World War II, a leading American teacher of Gandhian nonviolence, perhaps the prime mentor to the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the major planner and organizer of black America’s triumphal March on Washington in 1963,” Wicker wrote. “But Rustin also was gay, decades before the Supreme Court legitimated private sexual activity, and that cost him the backing of even some radicals, black as well as white, for whom he had been an eloquent and courageous leader for nearly 40 years.”

Rustin died in 1987 at the age of 75. Last year, not long after the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, President Obama posthumously granted Rustin the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

ALSO:

Flirting with disaster and dieties in ‘Foreign Gods Inc.’

Peek inside the Evelyn Waugh collection at the Huntington

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.