Where do art and the humanities belong? David Kipen on the new American Writers Museum

What were you doing in Los Angeles on the night of Aug. 10, 1939?

Actuarially speaking, hundreds if not thousands of native Angelenos can still answer that question. Even a 5-year-old on that night would only be 82 today.

But how many 5-year-olds in 1939 went to art openings? It’s just possible, then, that no one now alive visited a modest but elegant L.A. art gallery under a candy factory for the unveiling of the most important painting of the 20th century, Picasso’s “Guernica.”

What on earth was Picasso’s antiwar masterpiece doing midway between Bullock’s Wilshire and Lafayette Park, its paint only two years dry? Brought to town by European exiles like Fritz Lang and art dealer Galka Scheyer (and New York exiles like Dorothy Parker) as a fundraiser for Spanish Civil War orphans, did “Guernica” really belong here?

For a new project, I’ve been thinking hard lately about the question of where art and the humanities do and don’t belong. In federal budgets? In course requirements? And while we’re at it, in what universe does the newly opened American Writers Museum belong in Chicago?

The birth of the American Writers Museum

If you’re anywhere between Canada and Mexico and you care about reading, maybe you’ve already heard about the American Writers Museum. It aspires to become a showplace for the discovery and exploration of American literature, and it pretty much started in late 2009 when my office phone rang.

At the time, I was winding down my tenure as director of National Reading Initiatives for the National Endowment for the Arts. Loafers on the desk and the Post in my lap, I felt like Spade in Dashiell Hammett’s “Maltese Falcon” — a book I’d been evangelizing around American cities and towns encouraging my countrymen to read. There was a new NEA chair in town, and literature seemed to rank pretty low among his priorities. On my watch, the writing had always mattered most. Now the writing wasn’t just off the agenda, it was on the wall. I picked up on the first ring.

Seven floors down, I heard the security guard hand off the phone. In a papery brogue that sounded two weeks, tops, out of Dublin Harbor, a man’s voice said — actually said — “I t’ink I’d like to talk to someone about gettin’ a grant.”

As a federal arts administrator, you get calls like these from time to time: Hi, I’m working on a Civil War novel set on Alpha Centauri, and the first paragraph is almost done. Can you spot me a couple grand til Oprah calls?

Ideally, the calls go to voicemail. This one hadn’t. For whatever reason — maybe because I’d been on the needy end of one or two professional calls myself of late — I bit.

“What for?” I drawled, in no hurry.

Charm wafted up the line, fragrant as peat smoke, as I heard him utter the magic spell: “I’d like to start a museum of American literature.”

He said something else too, but I didn’t catch it, because I was already racing downstairs three marble steps at a time. Before he could hang up the phone, I was standing next to him. He looked somewhere in his mid-60s, beaming, bemused, his hair as silver as his tongue.

“Malcolm O’Hagan,” he said, offering his hand. He identified himself as a docent at the Library of Congress, retired from a successful career in engineering. I couldn’t help liking him. Nobody can. And so, right there by the guard station, just by lending Malcolm a sympathetic ear, I literally got in on the ground floor.

Within a month, I was squiring him around to share whatever literary friendships of mine looked to survive the looming loss of my job. I introduced him to the writer Marie Arana, who edited Book World at the Washington Post. I introduced him to the man who was my NEA boss, Dana Gioia. Trained up to New York to meet Max Rudin, who publishes the Library of America. All came on board to help bring this twinkling Irishman’s dream to life.

This year, on the night of May 16 in Chicago, after eight years of solicitous jawboning around the country from Malcolm, the American Writers Museum finally opened its doors to the public. Now and then I’ve consulted for it over the years, pushing hard for the inclusion of genre writing, screenwriting, funny writing, and other old hobbyhorses of mine. Before the museum smartly de-emphasized artifacts in favor of inspiration, I even pushed for a shelf of great writers’ dictionaries. Since Malcolm and I met, my ideas about reading promotion have run more to nonprofit storefront lending libraries than to major museums, but I still can’t wait to make my first pilgrimage to the place.

So what’s the American Writers Museum doing in Chicago? Civically, Chicago was the only city with big enough shoulders to support it. If the museum couldn’t be in New York (which all of us lobbied against), and it couldn’t be in Los Angeles (which I alone lobbied for), where better than Raymond Chandler’s hometown? What more American place, really, than the city where once you could have caught Saul Bellow, Ralph Ellison, Richard Wright, Nelson Algren, Margaret Walker and Studs Terkel around the same water cooler, all griping about the Federal Writers’ Project that was only keeping them alive and working?

If the American Writers Museum can find a way to tell complicated, timeless, local and national literary stories like that — while also inspiring a new generation of American scribblers —then good luck to it and godspeed.

Oh, the humanities

It may bear mentioning that, more than any early introductions from me, the Writers Museum wouldn’t have happened without a couple of key grants from the now-precarious National Endowment for the Humanities. This, even though nobody has ever agreed on whether literature really belongs to the humanities or the arts. There’s that pesky question again: Where do the humanities in general, and writers in particular, belong? And what’s a humanity, anyway?

After three years of teaching in UCLA’s Division of Humanities on the Writing Programs faculty, the humanities look to me like a Chinese student who writes so engagingly about food trucks that she may have to tell her family she isn’t cut out for medicine after all. The humanities look like a freshman from Boyle Heights trying to make a point about George Orwell’s essay “Such, Such Were the Joys” — the one about life as a scholarship boy, trying to belong among the toffs — without losing it completely. And in my case, the humanities are a Westwood-bred writer-turned-lending librarian, getting to meet each of these astonishing apprentice adults, watching their thoughts and vocabularies take turns outracing each other, figuring out where they belong.

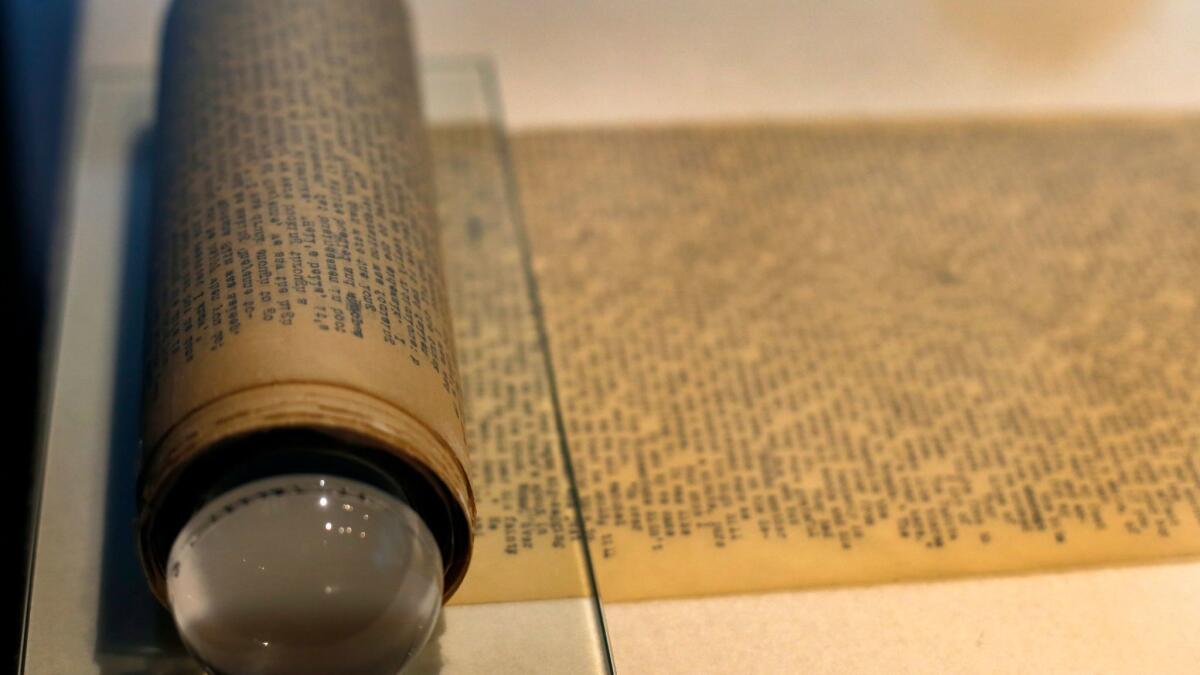

I’ve lately begun to suspect that the humanities are really just a high-minded alias for storytelling. Fiction, nonfiction, history, essays, criticism, dirty jokes, Picasso’s “Guernica” — it’s all storytelling, and anything with ideas and momentum is a story.

So, where were you on Aug. 10, 1939, when an L.A. gallery full of refugees, writers and artists, each confident they belonged anywhere but here, showed a painting that belonged in a museum, by an artist in Paris who belonged in Spain? Where were you this month when American writers finally rated a museum of their own? Where are you now? Do you belong there? What’s the story?

Kipen, founder of the Libros Schmibros Lending Library and the former NEA director of literature, now teaches on the UCLA Writing Programs faculty and is one of The Times’ Critics at Large. He is at work on “‘Guernica’ in Hollywood: The Night L.A. Grew Up.”

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.