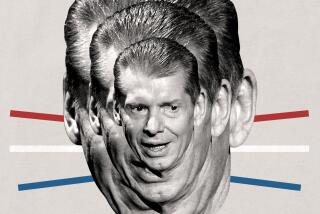

Mozilo says he wasn’t a dictator at Countrywide

Former Countrywide Financial Corp. chief Angelo R. Mozilo took the opportunity of his first public testimony since the mortgage giant’s near-collapse to depict the often-vilified company as the product of a lofty mission and high management standards.

Taking the stand as a defendant in a wrongful-firing lawsuit by a former Countrywide executive, Mozilo gave many curt answers but became animated and expansive when asked about his policies for the lender he co-founded in 1969 and built into the nation’s No. 1 home lender.

“Countrywide was about people,” he testified Tuesday in Los Angeles County Superior Court in Van Nuys. “Obviously, without quality people you can’t have a quality company.”

Countrywide was the largest purveyor of the subprime and other risky loans that devastated the mortgage industry, setting off a global financial crisis and deep recession.

Mozilo last year agreed to pay a $22.5-million fine to settle a Securities and Exchange Commission lawsuit — one of a series of suits alleging that Countrywide misled borrowers and investors about the risks of its lending — a penalty the SEC said was the largest ever for an individual in a case involving alleged misrepresentations to shareholders.

But the former chief executive said the goal from the beginning was “changing the lives of the American people” by making home loans to customers who could not have gotten them from other lenders.

“It was founded by two people driven … to make a difference,” Mozilo said, referring to himself and co-founder David Loeb, who left Countrywide in 2000 and died in 2003.

Analysts said Countrywide was skidding toward bankruptcy three years ago when Bank of America Corp. agreed to buy it. BofA installed new management after completing the takeover in mid-2008.

Mozilo’s testimony, a rare public appearance for the retired mogul, came in a suit brought by Michael Winston, a corporate strategy expert hired by Countrywide to help develop leadership training programs and executive-succession plans. Countrywide and BofA are also named as defendants.

Winston’s suit says Mozilo and the company turned on him after he refused to falsify a report about the firm’s management and its succession plans to a bond-rating firm and filed a regulatory complaint saying he and his team had been sickened by a chemical release at a building being refurbished by Countrywide.

Called as a witness by Winston’s lawyer, Charles T. “Ted” Mathews, Mozilo said he had wanted Winston fired because a leadership program he created was unimpressive and because he showed he wasn’t a team player by continuing to run a firm that booked speakers for events while he worked for Countrywide.

Mozilo said he didn’t insist on the firing, deferring to Countrywide’s human resources director, who in an e-mail said that she had authorized the outside work and that Winston was an “extremely talented, albeit eccentric, individual” needed to complete a project.

“I always regarded myself as a CEO, not a dictator,” Mozilo said. “I think the jury will note that I’m a pretty frank person — straightforward, I say what I believe. But I’m also willing to listen.”

Winston wasn’t fired then, but he contends Countrywide executives poisoned his reputation to such a degree that Bank of America didn’t keep him on.

Mozilo told the jury he held employees of the Calabasas lender to a high standard.

“My primary responsibility was to make sure that we recruited and retained the best and the brightest and rid ourselves of mediocrity. I always felt that mediocrity is comparable to cancer,” he said. “It spreads rapidly if you permit it to grow, and if you tolerate people who are not performing, it makes it very hard for the people who are working hard.”

Known as a snappy dresser, Mozilo, 72, testified wearing a black suit, a magenta tie and a white shirt with French cuffs.

A discussion of Mozilo’s fondness for cufflinks provoked smiles from jurors when Mathews displayed a set of boxed links bearing Countrywide’s logo and suggested Mozilo had given them to Winston as a token of appreciation.

“That’s absolutely untrue,” Mozilo replied, but he acknowledged that he and other executives had given away “thousands of them.”

Outside the courtroom, Mozilo, a longtime resident of the Sherwood Country Club in Thousand Oaks, appeared tired, walking slowly and leaning on a hallway railing. He declined to be interviewed.

In last fall’s SEC settlement, Bank of America, which assumed Countrywide’s legal liabilities, provided an additional $45 million to cover Mozilo’s disgorgement of what the government said were ill-gotten gains from selling stock while in possession of non-public information about Countrywide.

Countrywide’s former president, David Sambol, also a defendant in Winston’s suit, followed Mozilo on the witness stand, saying that when he was a Countrywide executive he never heard about the allegations in the case. .

Asked if he was shocked by the abruptness of an e-mail from Mozilo regarding Winston that directed a subordinate to “fire him immediately,” Sambol paused.

“No, probably not,” he answered. “Because it’s Angelo’s nature just to act that way when he doesn’t like somebody or has come to view somebody in a negative way.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.