French indignant over government plan to raise retirement age

Reporting from Amiens, France — Didier Remy has spent his life so intent on retiring on his 55th birthday that he and his wife even planned their children accordingly, wanting them to be grown by the time he stopped working.

So pardon a little indignant hand-waving as he ponders the prospect of Nicolas Sarkozy fouling everything up. If the French president has his way, Remy will find it tough to retire with his full state pension in 2015, as he carefully plotted 20 years ago.

“My life was organized around the idea that I’m going to leave work at that age,” said Remy, a lifelong employee of France’s state-owned railway, whose benefits are the envy of other Frenchmen, never mind long-slogging Americans. “It’s my goal. But it rests with the powers that be.”

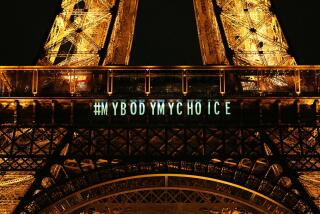

True to form in this protest-rife land, Sarkozy’s announcement that he intends to raise the national retirement age sometime this summer sent thousands of demonstrators spilling into the streets last month in opposition. But this time the French are part of a larger tide of anger and anxiety surging across Europe.

With budget deficits ballooning across the continent, and a huge bailout of debt-ridden Greece on the verge of taking place, officials across Europe say they have no choice but to boost retirement ages if they are to tackle a monumental economic problem compounded by declining populations and longer life spans.

But few issues are as sensitive in a region where the right to retire at a decent age, and retire well, is considered almost an inalienable social right. For many here, it’s one of the defining elements of their identity as Europeans, part of what they feel makes them different — more reasonable, more humane — from overworked, overstressed Americans.

“Old-age pension protection is at the heart of what is termed ‘social Europe,’ “ said Athina Vlachantoni, an expert at the Center for Research on Aging at the University of Southampton in southern England.

“Retirement protection is considered as hard-fought a victory for workers as the 35-hour week and [gender] equality legislation,” Vlachantoni said. “This is why pension reform is a hot potato in every European country.”

Of course, old-age benefits are a tricky political issue in the U.S. too: Pity the lawmaker who tries to fiddle with Social Security.

But the retirement age in the U.S., now 66 but set to rise to 67, has until recently outstripped that of almost every country in Europe. In nations belonging to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which includes the U.S. but is dominated by European states, the average retirement age a decade ago was just under 62.

In some countries, it’s even lower. Some Greeks — including hairdressers, who are deemed to work with dangerous chemicals — are allowed to quit working at 50. Such open-handed policies have bred tension with more frugal countries such as Germany, which is now on the hook to help rescue its Mediterranean neighbor from bankruptcy.

Even Germany, though, looked generous by American standards.

That was then, this is now.

For one thing, people are living longer. In Europe, someone who retires at 65 can expect to live 10 to 17 more years, and even more in richer nations, according to the statistics agency Eurostat.

At the same time, European women are having fewer babies, so societies are steadily graying, with fewer young people entering the labor force to replace older workers — and pay for the pensions of longer-lived retirees.

Couple that with levels of public debt that have alarmed investors and shaken faith in the euro, and the need to find a way to ease the strain of pensions on national budgets becomes acute.

In Ireland, whose economy was especially hard hit by the global recession, the government has proposed increasing the retirement age to 68 from 65. Germany now expects people to continue working until 67 instead of 65. The same holds true in Denmark, one of the Scandinavian nations famous for generous social welfare policies.

As the need for fiscal discipline hits home, the assault on the sacred cows of retirement age and pensions has come from reality-slapped governments on both the left and right.

But the issue is so vexatious that in Sweden, for example, parties across the political spectrum had to meet behind closed doors for several years to hash out a solution that could garner all-party support.

That doesn’t satisfy defenders of the status quo, who see the European way of life under threat. In February, a Spanish proposal to boost the retirement age was able to provoke street protests that an unemployment rate of nearly 20% failed to do.

Here in France, when the leader of the Socialist Party suggested that a retirement age of 61 or 62 should be debated, she came under so much fire that she had to backpedal on the idea within hours.

“We needed more than 15 years to win a retirement age of 60,” said Eric Aubin, a leader of the CGT, one of France’s largest unions. “The French are very attached to it, because we have a situation today of very deteriorated employment and working conditions that are unbearable.”

Surveys show the French to be among the unhappiest workers in Europe, despite laws that guarantee them at least five weeks of paid vacation from the moment they start their jobs. They ascribe their discontent to increasing levels of stress on the job, unreasonable demands from managers and rising workloads.

More than residents of almost any other European country, the French say they want to stop working as soon as possible. Their legal retirement age is already among the lowest in Europe. Most workers actually give up their jobs a little before turning 60.

“Even if today we live better, and our health coverage and healthcare are better, why does that mean we have to use that for working?” said Remy, the railway employee here in Amiens, a once-prosperous town in northern France that has fallen on harder times.

When he began working as a maintenance man for the SNCF railway service 30 years ago, at age 20, his contract allowed for retirement at 55. (Drivers can stop working at 50.) But changes afoot mean that he could be docked as much as 20% of his pension if he leaves the job as early as he planned, a monthly hit of about $400.

“That 20% is huge. So I don’t know financially if I’ll have the means to leave at 55,” Remy said.

He cited a commonly heard theme here: that older workers should willingly step aside to free up jobs for young people, especially during a time of heavy unemployment.

A higher retirement age, many say, would undermine that. But some analysts disagree.

“It’s not a simple zero-sum game,” said Monika Queisser, who works on pension issues for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. “Economies that grow and have a proper development and growth strategy create jobs for both young and old people.”

Officials must also decide thorny issues of fairness: Should a factory worker who uses dangerous equipment or performs arduous physical tasks be required to continue working until the same age as someone with a cushy desk job?

Jean-Robert Creunet thinks not. At 57, he’s spent his entire career in textile and furniture factories, working nightshifts for much of that time.

“Now I really feel it. Life expectancy has gone up — but in a wheelchair,” he said derisively.

The fact that countries throughout Europe are facing similar issues and deciding to raise their retirement ages means nothing to him.

“They can do what they want in other places. We’re in France,” he said. “It’s not a privilege. It’s a right.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.