She’s at home in the circus sideshow

- Share via

PUEBLO, COLO. — Jackie Molen isn’t the only star of “The Strangest Show on Earth.”

There’s also Sonny, a steer with a pair of stunted legs growing out of his back, and Daisy Mae, a red Holstein with two pink noses on her misshapen face.

But top billing at the Big Circus Sideshow goes to Molen, 24, who was born with only one tiny leg. The medical term is proximal femoral focal deficiency, but both she and the man who hired her have a different name for it.

“I’m the Human Tripod,” Molen said, sitting in her wheelchair as passersby at the Colorado State Fair gawked at a sign outside her tent: “Freak animals created by God, not by the hand of man.”

Some give in to the allure, forking over $2 to get inside.

Until last year, customers found a menagerie of animals, living and pickled, with an array of deformities: a three-legged duck, a pig with two noses and two mouths, and “Ertyl & Myrtle,” a double-headed turtle.

But sideshow owner Jim Zajicek wanted humans as well, so he hired Molen, and a man with shortened arms known as “Flipper Boy,” to perform -- roles harking back to an era Molen says she is sorry she missed.

“I like to think I’m continuing a tradition,” she said.

It’s a tradition viewed by many as a distasteful part of American history: the display of people with disabilities to entertain the masses.

Circus sideshows first became lucrative in the late 1800s, when it was considered educational to display people from other cultures, such as the South Pacific, said Robert Sabia, president of the Circus Historical Society. In the 1900s, the focus switched to people with unusual physical characteristics, but after World War II, interest in such shows waned.

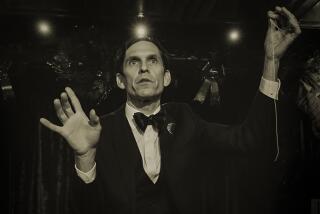

To Zajicek, a circus veteran in a bow tie and fedora, there’s still a place for sideshows. “The movers and shakers don’t think it’s politically correct,” he said. “But the masses still want to see this stuff.”

His is one of several sideshows that traverse the country, booking with carnivals and fairs whose officials can be persuaded to host them. Some demur when they hear the word “sideshow,” Zajicek said.

In Colorado, the state fair hasn’t had such an exhibit in decades, said fair manager Chris Wiseman, noting that fair officials didn’t seek out the sideshow, which was hired by the fair’s contracted carnival. When officials learned of it, their reactions varied.

“Some thought it was neat, a throwback to the ‘40s and ‘50s,” said Wiseman, adding they will gauge public reaction before deciding whether to allow it next year. “Some thought it belonged in another time.”

On a recent afternoon, Molen, a pretty, black-haired woman wearing a black sequined tank top and a black high-heeled sandal, sat sipping a Pepsi outside the tent entrance. She only works when Zajicek deems the crowds large enough, and then she climbs a small stage to perform a series of balancing acts alongside her boyfriend, fire eater Josh Bladzik.

Fairgoers glanced at her as they walked into the tent to gape at the placidly chewing animals that Zajicek has collected over the years, mostly from farmers, and the jars of animals -- some relics of 1940s shows, others recent acquisitions from veterinarians -- preserved in formaldehyde.

“Ooh!” shrieked a young girl as she stared at Laverne, a sheep with a fifth leg dangling from her belly. “Disgusting!”

Zajicek is always on the lookout for a new acquisition that will sell tickets but he says he draws a line at “self-made freaks” -- people who cover themselves in tattoos or surgically alter themselves.

“It’s stupidity to deform yourself for entertainment value,” he said. “What Jackie’s doing is she’s playing the cards she’s dealt. She’s an inspiration.”

Raised in Idaho, Molen studied gymnastics and martial arts. “When I was younger, I ran around on my hands and foot. I didn’t get teased very much. If anyone tried to tease me, I’d beat them up,” said Molen, who first joined a show four years ago.

Able-bodied people are the ones who seem most uncomfortable with her job, she said. But she views it as a form of advocacy for the disabled.

“I feel like I’m educating people about diversity and how people can be born different,” she said. “I’m in there doing amazing things. . . . This show is about what I can do. It’s not a pity party. I’m proud to be a freak.”

She could accomplish the same goal by working other jobs, said Andrew Imparato, president and chief executive of the American Assn. of People With Disabilities.

Depicting the disabled as objects of entertainment makes it harder for others to avoid being defined by their condition, Imparato said. “You can find people willing to do that for a living, but that doesn’t mean it’s good for society,” he said.

Under the tent, the reactions of fairgoers were mixed, but many took the same stance as the fair manager: If Molen was OK with it, so were they.

But James Cordova, 47, of Pueblo, confessed to some discomfort. Displaying animals is one thing, he said, but a person is another. “It can be kind of dehumanizing,” he said.

Jo Mitchell, 80, of Colorado Springs, recalled the risque exhibits of her youth that included a hermaphrodite hidden behind a curtain.

“This is minor,” she said, “compared to what they used to have.”

--

Correll writes for The Times.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.