First war, now peacemaking

- Share via

GARMSER, AFGHANISTAN — Gola Akar, a black-bearded farmer, did not seem certain whether a monthlong Marine assault here had improved or retarded his business prospects.

On the one hand, the Marines killed or drove out Taliban fighters who had commandeered his mud-wall compound. But the fighting came at the height of the poppy harvest, costing Akar thousands of dollars in drug profits.

“Since you came, things are better,” Akar told 1st Lt. Shaun Miller, a slender, easygoing Marine who led a patrol past his compound one recent morning. “But who’s going to pay me for my lost poppies?”

Miller told him the U.S. government wasn’t in the habit of paying for lost narcotics profits. But Miller patiently wrote down the damage that Akar said the Marine assault had caused to his windows, roof and walls, and promised to pay cash compensation.

Throughout May, Marines pounded a Taliban stronghold here in the southern province of Helmand near where fellow Marines first set foot in Afghanistan in 2001 to help topple the Taliban regime. It was the first time in the 6 1/2 years of war since then that U.S. forces had reentered the area, which is crisscrossed by three major insurgent infiltration routes from Pakistan and is one of the world’s top opium-producing regions.

British forces have maintained a base just north of here, but commanders say the United States and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization have lacked sufficient forces to mount an offensive in the region, in part because of the U.S. focus on Iraq.

With the Taliban resurgent in the south, the Marines were deployed specifically to battle entrenched militants. Within a month, they routed the Taliban fighters and disrupted infiltration routes.

Now, they are trying to win over Afghan civilians who are trickling back to their damaged homes.

Officers such as Miller are leading patrols through poppy and marijuana fields to assess farmers’ losses. The Marines also have been forced into other unfamiliar roles -- as quasi-diplomats, humanitarian workers, moneymen and nurses.

“Not exactly what I signed up for,” Miller said. Sometimes, he said, he felt like an insurance adjuster.

The Marines are the only source of security here. The weak Afghan government is nowhere in sight. The Afghan police fled a Taliban takeover two years ago. The nearest Afghan army unit is posted several miles north, with the British forces.

The Marines are rushing to solidify their combat gains while enlisting civilian support in behalf of the absent Afghan government. Time is precious.

The Marines, from Alpha Company, 1st Battalion, 6th Marine Regiment, 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit, were scheduled to return home to Camp Lejeune, N.C., in October, but Thursday the Pentagon extended their stay by 30 days.

“The honeymoon’s almost over,” said Capt. Sean Dynan, commander of Alpha Company, which controls about 4 1/2 square miles of lush farmland that is home to 3,000 to 5,000 Afghans. “Pretty soon, it’s going to be: What have you done for me lately?”

The Marines live in harsh conditions, sleeping on the ground amid goat droppings and flies.

The heat and dust are debilitating. There is precious little shade; they cluster under a small tree, changing positions as the sun moves across the sky.

The men wash in a communal well. They survive on bottled water and packaged meals, or MREs. There is no electricity, no plumbing. They burn their waste.

1st Lt. Steven Bechtel, an artillery officer, has set up a cash-dispensing office in a mud hut, receiving villagers who file claims for war damage.

“It’s kind of ironic,” Bechtel said. “A few weeks ago, we were blowing these places up. Now, we’re totaling up the damage and paying for it.”

The payment center is in a compound that also houses company headquarters. The property is owned by the local police chief’s nephew, who is paid about $65 a month in rent and was given a one-time damage payment of about $1,500.

One day, the landlord asked for permission to dig beneath a mound of firewood in the compound, Dynan said. The man withdrew several trunks that contained what appeared to be opium and hashish, and went on his way.

“We let him go; we’re not here to hurt people’s livelihoods,” Dynan said. “We’re not in the drug interdiction business.”

Bechtel worked steadily through the punishing heat -- well above 100 degrees -- to process a stream of bedraggled people seeking reparations. A patrol was sent to each applicant’s compound to photograph damage and record the property on military maps.

Bechtel said he had promised about $105,000 to 240 applicants.

But there was a hitch: Alpha Company didn’t have any cash to make the payments. Because of new Pentagon regulations, the money was held up.

So Bechtel improvised. He tore yellow notebook paper into small slips and wrote down the names, locations and tribes, along with the amount of damages owed.

The applicants went home with the slips that committed the Marines to pay up once the money arrived.

Sher Zaman, a wizened man in a floppy gray turban, stared at his yellow slip in bewilderment. But he brightened when Sgt. James Blake told him through an interpreter that he would receive $3,200 for his ruined roof and mattresses burned during the Marine assault.

The sergeant asked Zaman to report on any Taliban in his area. The old man shook his fist.

“You guys are good guys trying to help the people [mess] up the bad guys,” the old man said. “If I see the bad guys, I’ll catch them myself. I’m old, but I can catch them.”

Several other people also provided information, warning the Marines that insurgents wearing explosives-packed vests or dressed in women’s burkas planned suicide attacks.

“Don’t leave us alone,” said one applicant, Habib Rahman, a farmer with a crimson-dyed beard. “If you leave, the bad guys will come right back.”

Yar Mohammed, 80, who hobbled into the payment hut using a cane, described a damaged wall, gate, doors and steel roof beams. Told that he would be given a yellow slip good for $2,375, Mohammed shook his head and said, “This is not enough.”

Blake, a mortar man, explained that the payments for repairs were based on estimates from local contractors fed into an Excel program.

“OK,” Mohammed said, shrugging. “You decide.”

He happily provided his fingerprints and posed for a registration photo.

The next day, the compensation system got more complicated. Alpha Company’s payment center was moving six miles north, to be consolidated with other units. Any Afghan with a yellow slip would have to make the trek there.

From a smaller compound nearby, Miller and his platoon rose at 4 a.m. to patrol in the coolest part of the day. They slogged through fields, crunching dried poppy pods under their boots and brushing past lush marijuana plants taller than any Marine.

“What are you guys doing here?” a shepherd named Noradeen yelled at the troops as they stumbled across his flock in the rosy light of dawn.

“Assessing damage!” Miller called back, through an interpreter.

Noradeen accepted Miller’s offer to tour his compound, where the shepherd pointed out damage to doors and walls. He said he had fled with his sheep after the Taliban took over the compound.

“Oh yeah -- that’s true,” Miller said, giving Noradeen a yellow slip.

“We spent a week right next to this place. We had to blow it up to get the Taliban out of here.”

At the next compound, Abdul Rakani, a bony man with one good eye, complained that the fighting had reduced his opium profits from $10,000 to about $3,000 because he could not harvest all of his poppy crop.

Rakani pointed out damaged windows and doors. Miller gave him a yellow slip but declined to pay for other damage, which the lieutenant said was caused by insurgents who had commandeered the compound.

Down a dirt path, the patrol encountered three young men with wild black beards and the dark turbans favored by Talibs. From a distance, Miller ordered them to roll up their sleeves and raise their robes to prove they were not hiding explosives. They complied.

The men told Miller they were farmers returning from a night’s work in their fields. They were afraid to work during the day, they said.

“We’re afraid the Marines will kill us,” one man said.

Civilian casualties, especially those caused by airstrikes, have enraged Afghans. But in a month of fighting here, the Marines said, only two civilian death claims were filed.

At midmorning, the patrol returned to its mud compound, the Marines’ vests drenched with sweat. There would be dozens more patrols before they left Garmser.

U.S. and NATO commanders are discussing which forces -- U.S., NATO, Afghan or some combination -- should replace the Marines, said Col. Peter Petronzio, commander of the 24th Marine Expeditionary Unit.

“It’s important that they come in and capitalize on our success,” Petronzio said. “It’ll take a bit of time. You need to eat this elephant one bite at a time.”

For Miller, sunburned and exhausted after another three-hour patrol, the hard work his men had put in this spring and summer was too precious to be wasted. He knew the insurgents were eager to return to their former stronghold.

“The key for us is: It can never go back to the way it was,” he said.

--

--

On latimes.com

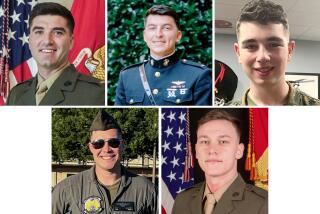

Winning their hearts

A photo gallery documenting the work of Marines in Afghanistan is at latimes.com/world.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.