Edwards’ machine rolls across Iowa

- Share via

NEWTON, IOWA — Here in the heart of Jasper County, a flyover patchwork of green pasture and golden cornfield, lies every ingredient for a John Edwards victory in the critical Iowa caucuses.

The Maytag plant at this small town’s heart is slated to close in less than a month. Edwards has been a regular visitor to the local union hall, and when the Democratic presidential hopeful rails against globalization, it is often the plight of this factory that he rues.

The farm towns sprinkled among Jasper County’s rolling hills form the core of Edwards’ rural strategy. Even history is in his favor: Though John F. Kerry won Iowa in 2004, Edwards beat him by nearly double digits in this working-class enclave east of Des Moines.

But look a little closer, and you’ll also see some of the biggest challenges facing the former senator from North Carolina as he struggles against rivals with bigger bankrolls and fresher faces.

Dennis Parrott spearheaded Edwards’ Jasper County efforts in 2004, but these days, he can’t decide between the self- described mill worker’s son and rival Barack Obama. He is not alone.

“John’s gotten very far left, more left than I’d like to see him,” said Parrott, who prefers yesterday’s genial centrist to the elbow-throwing liberal he sees today. “Maybe it’s the hedge funds, the expensive haircut, the expensive house. That’s where I’m having a problem.”

There are three big questions confronting John Edwards: Does he need to finish first in Iowa to keep his presidential hopes alive? Could he actually win the first-in-the-nation caucuses, a traditional springboard to later victory? And, finally, will he?

To date, there are only two easy answers: “Yes.” And “yes.” After that, it’s “Who the heck knows?”

Edwards himself offered this viewpoint in a recent interview about his Iowa strategy: When it comes to the Hawkeye State, “I think anybody who doesn’t win is going to be in an uphill fight.”

Still, Edwards is believed to have the deepest political organization in the state. He has chairmen in all 99 counties and relationships dating back to his earlier run, when he came in a strong and surprising second behind Kerry and ahead of front-runner Howard Dean.

“I know what’s doable in this state, and I think Edwards can win Iowa,” said Sarah Swisher, state political director for the Service Employees International Union, who has attended every caucus since 1976. “It’s very doable.”

But doable and done are different things.

Many Edwards optimists point to the 2004 primary season, when Dean was practically anointed the Democratic candidate for president before Columbus Day, only to spin out of control when the caucusing and voting began several months later.

“The big difference is, of course, that Hillary Clinton is not Howard Dean,” said Peverill Squire, professor of political science at the University of Iowa. “Hoping that somehow things are going to unfold in 2008 the same way they did in 2004 is probably wishful thinking.”

Town in transition

Doug Bishop is driving the tree-lined streets of Newton, pointing out the highlights of his community in transition. Over there is the brand-new Iowa Speedway, a 25,000-seat motor sports stadium that is a key to Newton’s economic future.

Those stately houses on First Avenue used to be home to Maytag executives. And that hulking factory hard by a cornfield was where thousands of union workers churned out washers and dryers.

Back in 2001, before Maytag began laying off workers, 10,000 machines were built in a single day, Bishop said, and “this parking lot would be full. It’s just a scattering of cars now.”

And they’ll be gone Oct. 26. That’s when Whirlpool, which last year finalized a deal to buy Maytag, will end production here for good.

At its peak, Maytag employed more than 4,000 union workers and headquarters employees in Newton. Until he was laid off in 2004, Bishop was one of them. Today, he is treasurer of Jasper County; two of his employees are also laid-off “Maytaggers.”

While nearly all of the Democratic candidates for president have visited Newton at least once, Edwards has been a regular presence since at least the 2004 presidential campaign, when he walked the picket line with striking Maytag workers.

He has visited the union hall to hear their stories. And he highlighted their plight last month in a speech on fair trade practices, wondering “who was looking out for these workers in Newton? . . . Not Maytag. And certainly not anyone in Washington, D.C.”

Such fervor is one reason for Edwards’ support in Jasper County; what he describes as his hardscrabble history is another.

On the campaign trail in Iowa last week, he talked about being the first person in his family to go to college -- and how he felt “a little bit like a hick” when he finally got there.

“He came from a small town in the Carolinas where a closing mill devastated the community,” said Bishop, a strong Edwards supporter. “He knows what we’re going through.”

Investments questioned

Late-summer sun is beating down on 15,000 hard-core Democrats and the presidential hopefuls who want their support out at Tom Harkin’s 30th annual steak fry. There are hay bales, farm equipment and a multi- story American flag.

Flanked onstage by his chief rivals, Edwards cranked up his edgy inner populist. He called for universal healthcare and a rise in the minimum wage, and he slammed Washington for its reliance on lobbyists.

“I don’t know about you,” he said, “but I don’t want to see us replace corporate Republicans with corporate Democrats.”

Angie Smith, who assembles dryers at the Maytag plant, commandeered one of the blue plastic megaphones handed out by legions of Clinton workers and cheered, but Claire Celsi wasn’t buying it.

Celsi had supported Edwards, even blogged for him, largely because of his “anti- poverty, two-Americas platform.” Then she heard reports of lavish living and “couldn’t reconcile it in my head.” Now, she said, she will caucus for Clinton.

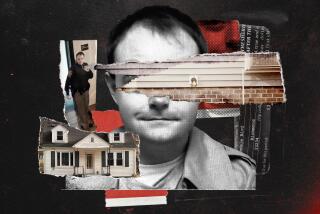

Edwards’ widely derided $400 haircut and 28,000-square-foot mansion have raised eyebrows and questions alike. But perhaps more significant here is his connection to a hedge fund that invested a small amount in Whirlpool Corp. stock as the manufacturer was planning to close Newton’s Maytag plant.

Edwards earned $480,000 in 2006 working as a part-time senior advisor to Fortress Investment Group, a New York-based hedge fund that caters to select high-income investors and invests globally, his campaign aides have said.

On March 31, 2006, the hedge fund owned 9,867 shares of Whirlpool stock, according to documents filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The same day, Whirlpool announced it had finalized the deal to buy Maytag.

Less than two months later, Whirlpool announced that it would close Maytag plants in Iowa, Illinois and Arkansas. SEC filings from March 31, 2007, show that Fortress had purchased more than 74,000 additional Whirlpool shares after the deal to buy Maytag closed.

The Edwards campaign argues that the candidate had no part in Fortress’ purchase of Whirlpool stock, the bulk of which was made after he stopped advising the fund. In addition, they say, Fortress actually owns less than a tenth of 1% of Whirlpool’s total shares.

“Sen. Edwards has no direct investments in Whirlpool, and the truth is that the amount of Fortress’ holdings in Whirlpool is infinitesimal,” spokesman Eric Schultz said.

“That being said, Sen. Edwards is proud of his fight for union workers at Maytag and all across America,” he continued, “and baseless attacks will never stop him from speaking out.”

Edwards no longer advises the hedge fund, but he and his wife, Elizabeth, still have $16 million in Fortress holdings. The fund is also a rich source of campaign money for the candidate -- at least $233,000 in donations from executives and other employees of Fortress and their relatives, a review of his campaign finance reports shows.

Focus on smaller places

Many joke that Edwards set up shop in the state shortly after the millennium and never left, but there are some big bene- fits for his repeat performance here.

“Without question,” said Gordon Fischer, former chairman of the Iowa Democratic Party, “because he’s been here so long, he’s got the organization to beat.”

Edwards also has focused on rural Iowa with an intensity largely unsurpassed by his rivals. In the 2004 campaign, he stumped in every one of Iowa’s 99 counties and is on track to do the same again.

Although some disagree with such an analysis, Edwards has embraced the belief that “smaller places have a disproportionate influence. And so organizing in Jasper County -- and all parts of Jasper County -- matters.”

Last week, he unveiled his education plan at Brody Middle School in Des Moines, vowing to institute universal preschool, reward successful teachers on high-poverty campuses and create a national teacher university.

But when the speech ended, he headed off to tiny Guthrie County, where cellphone service and traffic are equally spotty and his folksy charm played better in 2004 than any other place in the state.

In the quiet hour before the Guthrie Center Tigers met the Treynor Cardinals on the football field, Edwards strode into the neat high school, rolled up his sleeves and went to work.

To the woman who asked why a rich guy like Edwards would want to lead a country in one “heck of a mess,” he said he was running for president “on behalf of those families that worked in the mill with my father, on behalf of the families that I grew up with.”

He told the rapt audience, all work shoes and weathered faces, about the day he sat in a hospital room with his wife, Elizabeth, hearing bad news about her cancer diagnosis.

“I said to her then, ‘Whatever you need me to do, I will do it,’ ” he continued. After all, they’d been married for 30 years, and “I’d do anything for her.”

“And she said, ‘What I want you to do is: I want you to be president of the United States and stand up for the people we’ve been trying to stand up for our whole lives.’ That’s why I’m running for president.”

To the elderly man who gave a short rant about immigrants, test scores and the No Child Left Behind Act, he acknowledged, “It’s a mess, isn’t it?

“No child ever learned anything by taking a test,” he said with a smile. “You don’t make a hog fatter by weighing it.”

--

Times staff writer Dan Morain contributed to this report.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.