Salsa holds sway in L.A.

ONE of the first things that you learn about salsa dancing is that on the count of four you are supposed to stop moving your feet and take a short pause. This syncopated break pushes you to shake the hips, and it can be shortened or stretched according to the mood of the song. The pause is the key to salsa -- the very essence of its mystique. On a good night, the pause can make you feel that the entire world has stopped turning.

On a weeknight a few months ago at Mama Juana’s, the cozy Studio City nightclub, I found myself pondering the elusive nature of that very salsa step. During the last 10 years, I had developed a torrid love affair with tropical music, become a Latin music critic and amassed thousands of albums. But my dancing skills were still nonexistent -- owing to my innate clumsiness, not to mention a morbid Buenos Aires childhood spent listening to my brother’s Pink Floyd records.

After a number of false starts, I had found a teacher with the titanic patience to tutor a student such as myself. Ken Baldwin, a soft-spoken Japanese American, laid out simple patterns with precise instructions, focusing on the power of salsa to inspire your soul, and less on the showy pirouettes most students expect to learn.

But in Los Angeles, it’s often what you learn to appreciate after the dance lessons that’s just as magical: a performance by a superlative salsa band. The lively variations on the feverish combination of Afro Caribbean music’s percolating percussion and funky brass riffs run like threads through the fabric of a city where salsa thrives thanks to dozens of orchestras that, against all odds, continue to ply their trade.

“I know it’s kind of incredible to say this, but Los Angeles has more of a salsa scene than New York these days,” says Oscar Hernández, leader of the Spanish Harlem Orchestra, the most successful and respected salsa combo in the U.S. “In New York, the quality of the music may be a bit higher, but the generation that supported salsa 30 years ago has moved on. In L.A., Latinos from all walks and nationalities are getting into this music, which explains why the scene is bigger here.”

The variety of available soundscapes is actually breathtaking.

Consider:

* After a number of years following the aggressive Cuban style known as timba, Son Mayor has recently returned to the classic sound of ‘70s New York, when artists such as Willie Colón and Ray Barretto took the movement to its creative apex by combining the raw danceability of Afro Cuban styles with big band jazz and gritty R&B; influences. Son Mayor’s version of the Roberto Roena classic “Con Los Pobres Estoy” is, in the words of bandleader Erasmo “Eddie” Ortiz, “brutally violent.”

* Led by conservatory-trained trombonist Denis Jirón, Rumbankete anchors its epic sound on majestic layers of trombones -- following the aesthetic of pioneering orchestras such as Eddie Palmieri’s La Perfecta and Manny Oquendo’s Conjunto Libre. Rumbankete’s cover of the Libre standard “Alabanciosa” is a sophisticated delight.

* Favoring a lighter, more elegant sound, Charangoa is the modern version of a typical Cuban charanga -- a tropical ensemble that combines joyous violins with acrobatic flute solos. The ultimate charanga band was Cuba’s Orquesta Aragón. Charangoa follows its sunny, ever-smiling parameters.

* The chocolate-voiced Ricardo Lemvo, a native of Congo, has fused the rootsy vibe of classic Cuba with the spiraling guitars of Congolese rumba. The result is dance music at its most transcendental. Lemvo is the only local bandleader who regularly releases high-quality CDs of original material.

* Led by Costa Rican trumpet player Oswaldo Bernard, Opa Opa is noted for the voracious appetite with which it embraces all shades of the tropical palette: The band performs Dominican merengue, Cuban boleros, Puerto Rican bomba and Colombian cumbia with equal panache.

* Sponsored by Albert Torres, the dancer and promoter who is almost single-handedly responsible for the creation of the local salsa scene, former auto mechanic Johnny Polanco has developed into a talented multi-instrumentalist and leader of a well-oiled ensemble that performs virtually every day of the week. Their cover of Spanish Harlem Orchestra’s 2004 scorcher “Un Gran Día en el Barrio” is almost as good as the original.

The list goes on: Yari Moré. Chino Espinoza y los Dueños del Son. Orquesta la Palabra. The Echo Park Project. Susie Hansen. Octavio Figueroa y la Combinación. Luis Centeno y su Orquesta Melaza. And many more.

A big influence

Hernández, a quintessential New Yorker, rose as one of the most talented pianists and arrangers in the field during the ‘80s, when he recorded seminal albums with Barretto and Rubén Blades.

Last year, Hernández got married and moved to L.A., where he spends most of the time when he is not touring with the Spanish Harlem Orchestra. During this year’s edition of Albert Torres’ Salsa Congress, he was invited onstage by venerable Puerto Rican combo La Sonora Ponceña. The prospect of a local orchestra led by him could revolutionize the entire scene.

“I’ve thought about forming a local band that I could play with whenever I am in town,” he says. “The problem is that many of the salsa musicians in L.A. are underpaid and disrespected. They are in a situation where they play four sets a night and get $80 for their effort. I refuse to work on that level. With the Spanish Harlem Orchestra, the musicians are well paid. I’ve made it a point to emphasize quality over quantity.”

Tropical bands have been criminally underpaid from the very inception of the genre. But the musicians carry on, undeterred. The cliché, in this case, applies: It’s all about the music.

“The local bands, we’re all on the same boat,” Opa Opa’s Bernard says with a laugh. “None of us is rich, but we all take turns performing in the few available venues. You don’t play this music for the money. You do it for love.”

Says Rumbankete’s Jirón, who has performed with Kanye West, Sting, Queen Latifah and the L.A. Philharmonic: “Having my own salsa band plays a different role in my life. It’s like therapy.”

Musicians are not the only ones who find therapeutic elements in this music. “I can have the worst day ever, but the moment I get on the dance floor, it all goes away,” says Lisa Bellamore, a publicist who learned salsa dancing when she lived in Boston. “The environment seems incredibly soulful to me. It’s a space where it’s OK to let go. When you hear those bass lines -- that beat that drives everything in salsa -- you have no choice but surrender to it.”

According to Son Mayor’s Ortiz, it is the support of the dancers that keeps the local scene moving.

“We owe our very existence to them,” he offers. “And they’re not only Latinos. Many of our fans are Anglos who got the salsa bug, and when we play at Alhambra’s Granada, there are a lot of Asians on the floor. I think it’s great that all these different ethnic groups are having so much fun with our music.”

A promotion

As the months went by, my lessons at Mama Juana’s began to pay off. The circle was beginning to close: My dancing was somewhat adequate. I would not embarrass my wife and daughter at family parties anymore.

Most important, my love for the music was stronger than ever. Performances by the likes of Son Mayor and Polanco reinforced my notion that salsa is the quintessential expression of the Latin American experience. It has humor and tragedy, eros and Thanatos, academic virtuosity and streetwise sensibility. At its best, salsa rocks harder than rock.

On a recent return to Mama Juana’s, I asked Baldwin about that special moment in the basic step -- the hesitation on the four count.

“The pause is like that moment when you throw a ball in the air -- it’s not going up anymore, but not coming down either,” he says. “For a second, the ball is floating, transferring its energy from rising to falling. The energy is still there, but it’s suspended in the air, weightless.”

Suddenly, he looked surprisingly serious.

“Don’t come back here on Wednesdays,” he said sternly. “I don’t want to see you in the beginner’s class anymore.”

He added with a smile:

“From now on, you are an intermediate student.”

--

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Where to find the beat

The lessons

Mama Juana’s

3707 Cahuenga Blvd., Studio City. (818) 505-8636. Classes at 7:30 p.m. on Tuesdays (intermediate), Wednesdays (beginner), Thursdays (advanced), Fridays (beginner) and Saturdays (beginner). $10 to $15 cover or dinner reservation.

Granada

17 S. 1st St., Alhambra. (626) 227-2572. Class at 8 p.m. on Saturdays. $15 cover.

El Floridita

1253 N. Vine St., Hollywood. (323) 871-8612. Class at 8 p.m. on Wednesdays. $15 cover or dinner reservation.

The Mayan

1038 S. Hill St., Los Angeles. (213) 746-4674. Class at 9 p.m. on Saturdays. $18 cover.

Monsoon Cafe

1212 Third Street Promenade, Santa Monica. (310) 576-9996. Classes at 7 p.m. (advanced) and 8:30 p.m. (beginner) on Wednesdays. $10 cover.

Steven’s Steakhouse

5332 Steven’s Place, City of Commerce. (323) 723-9856. Classes at 7 p.m. on Mondays, Tuesdays and Wednesdays, and 3 p.m. on Sundays. $10 cover.

The bands

www.sonmayor.com

www.johnnypolanco.net

www.tabacoyron.com

www.webmenudo.com/rumbankete.htm

www.susiehansen.com

www.makinaloca.com

www.opaopa.biz

www.charangoa.com

www.octaviofigueroa.com

www.myspace.com/chinoespinoza

www.yarimore.com

www.palabraonline.com

www.theechoparkproject.com

www.orquestamelaza.com

Upcoming

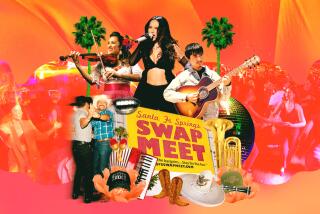

L.A. Salsa Festival

Tribute to El Cantante, Greek Theatre, 2700 N. Vermont Ave., L.A. 7:30 p.m. Sept. 22. $50.75 to $95.75. (323) 665-5857.