How Zell’s offer for Tribune might work

- Share via

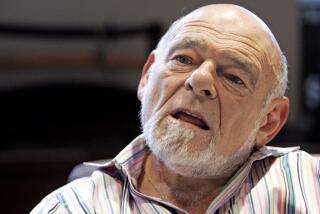

As the clock ticks down on Tribune Co.’s self-imposed deadline of Saturday for auctioning off the big media company, much is unknown about the apparent favored bid from Chicago real estate magnate Sam Zell and how it would be structured.

Zell, 65, has said little publicly except that he would invest $300 million in cash and become the minority partner of a newly created employee stock ownership plan that would buy up the company’s shares and take Tribune private. Zell declined an interview request Wednesday.

A Tribune spokesman said Wednesday that the board of directors was expected to make a decision by Saturday on the fate of the Chicago-based company, the parent of the Los Angeles Times, KTLA-TV Channel 5, the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Cubs baseball team and many other newspapers and TV properties.

An executive within Tribune said the board was scheduled to meet Friday and was expected to announce a deal with Zell that day. Financial news site TheStreet.com reported Wednesday that Los Angeles billionaires Eli Broad and Ron Burkle, who complained last weekend that Tribune was giving their bid short shrift, had resumed talking with Tribune and could make a counter-bid before the deadline. Broad and Burkle did not return phone calls seeking comment.

“The situation is very fluid,” said another person close to the negotiations.

Some hints about the structure of the Zell bid have surfaced in conversations with several people familiar with the auction, all of whom declined to be identified because the process is supposed to be confidential. Those hints, together with comments from finance and legal experts, suggest ways that a Zell buyout could work. Until Zell or Tribune supplies more details, however, any picture is speculative.

Zell values his bid at $33 a share, according to a person familiar with the bidding. With 240 million Tribune shares outstanding, that implies a price of nearly $8 billion, not counting the nearly $5 billion in debt on Tribune’s books.

The debt could be assumed or replaced with new debt, but either way, Zell and the new employee stock plan would have to raise about $12.5 billion to pull off the buyout.

Lenders would demand at least $2 billion of equity and probably more, meaning that $10 billion is about the maximum amount that could be borrowed, according to a New York-based investment banker who declined to be identified because his firm has worked with some of the parties involved in the auction.

Where would the $2 billion or more of equity come from, if Zell plans to contribute only $300 million?

One possible source is the McCormick Tribune Foundation, which, with 13% of the stock, is the company’s second-largest shareholder, behind the Chandler family. If the foundation reinvested its proceeds from the buyout into the private successor company, that would provide about $1 billion of additional equity.

However, such a move probably would attract criticism because the foundation has been under pressure to diversify its investment portfolio, about 75% of which consists of Tribune shares.

Reinvesting in the new Tribune would not change the 75% figure but would probably increase the foundation’s risks because the private company would be more laden with debt. A spokesman for the foundation declined to comment Wednesday.

Zell has said he would keep Tribune’s top executive corps in place, according to a person familiar with the negotiations. Typically in a going-private transaction, management is encouraged to invest cash of its own, which would account for another chunk of equity but probably only a couple of million dollars.

Another possible source: Tribune’s defined-benefit pension funds, which held assets of $1.76 billion as of Dec. 31, according to a company regulatory filing. The plans -- including one covering employees of Times Mirror Co., The Times’ corporate parent before its 2000 sale to Tribune -- have mostly been frozen, meaning that no new beneficiaries are being added or new contributions being made. With the phasing out of the pensions, Tribune employees’ main source of retirement savings is 401(k) investment plans, to which the company contributes.

Robert Willens, a tax and accounting expert with Lehman Bros. in New York, said the company could decide to invest a portion of the pension assets in the new Tribune without seeking the beneficiaries’ permission.

The advantage of using an employee stock ownership plan, or ESOP, in a buyout is primarily that it would allow the new Tribune to escape taxes on principal and interest payments on its loans. Typically, only interest payments are deductible.

In exchange for its role as the borrowing vehicle, the ESOP would receive a significant ownership stake in the company.

The stock would be pledged as collateral for the loans and would be released into the employees’ accounts as the loan was paid down. Because the shares would no longer trade on a public exchange, an appraiser would be hired to make an annual valuation of the stock.

Where would the money come from to pay down those loans? Because the ESOP would have no earnings of its own, the company would make tax-free annual contributions to the plan, possibly in lieu of the payments it now makes to the employees’ 401(k) plan. That pool would be used to pay off the loans.

There is a limit to how much the ESOP could borrow, because federal law allows an employer to contribute a maximum of 25% of an employee’s salary -- up to $100,000 in salary -- on a tax-free basis, according to Willens of Lehman Bros.

And not all of Tribune’s 21,000 employees qualify for such contributions. The maximum amount of Tribune’s potential ESOP contributions could not be calculated Wednesday, but that would determine the maximum annual tax-free principal and interest it could pay and thus dictate the size of the loan.

Any borrowing beyond the ESOP’s limit probably would have to be done by the new Tribune directly, which might lead it to employ another tax-advantaged structure, known as the Subchapter S corporation.

A person familiar with the negotiations said Zell was considering such a structure as part of his deal. Such corporations pay no regular corporate taxes but are required to pay all their annual profits to their investors, who then pay personal taxes on those dividends.

For a company taking on far higher debt even as revenues decline industrywide, the new Tribune would face an increased chance of insolvency. How employees would be protected is unclear.

For such questions, the ESOP would be represented by a trustee with a fiduciary responsibility to the employees. In a deal as closely scrutinized as a Tribune buyout would be, Willens said, the trustee probably would be a large, independent institution such as a major bank.

Although Zell has said he does not plan to break up Tribune, some observers believe that he might sell some properties such as the Cubs to pare debt after a buyout. The Cubs contribute little if any profit to Tribune, yet could fetch $500 million or more in a sale.

Tribune has sold about $500 million of assets since last summer, a campaign that received a setback Wednesday when a federal judge in Hartford, Conn., temporarily blocked the pending sale of the Advocate of Stamford, Conn., to Gannett Co., according to the Associated Press.

U.S. District Judge Alfred V. Covello granted a preliminary injunction sought by 36 unionized newsroom employees who feared that Gannett would ignore their contract should the sale go through. The injunction expires April 6, by which time an arbitrator is expected to rule on the union’s request for assurances that Gannett will honor the contract.

ESOPs have been used previously in newspaper-company buyouts but never involving a public company the size of Tribune.

In 1983, the family that controlled the Peoria (Ill.) Journal Star created an ESOP for the purpose of transferring ownership to the employees over a period of 10 years.

The deal eventually became too successful for its own good. An economic rebound in the mid-1980s boosted the value of the stock and spurred the employees to borrow money to buy the remainder more quickly.

By the early 1990s, the stock’s value had increased so much that employees started retiring early on small fortunes.

The wave of redemptions created a kind of run on the bank, threatening the company’s solvency.

As a result, the employees and management agreed in 1995 to sell the company to La Jolla-based Copley Press Inc., parent of the San Diego Union-Tribune.

Times staff writer James Rainey contributed to this story.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.