A fertile valley for the GOP

FOR MORE than a decade, California Republicans have endured hard political times. Aside from the governorship of Arnold Schwarzenegger, the party has had few electoral successes since the mid-1990s.

The GOP can take some heart, however, from developments in one region of California: the San Joaquin Valley, where a partisan realignment has quietly taken place. As measured by two-party registration, Republicans are now the majority for the first time since the Depression.

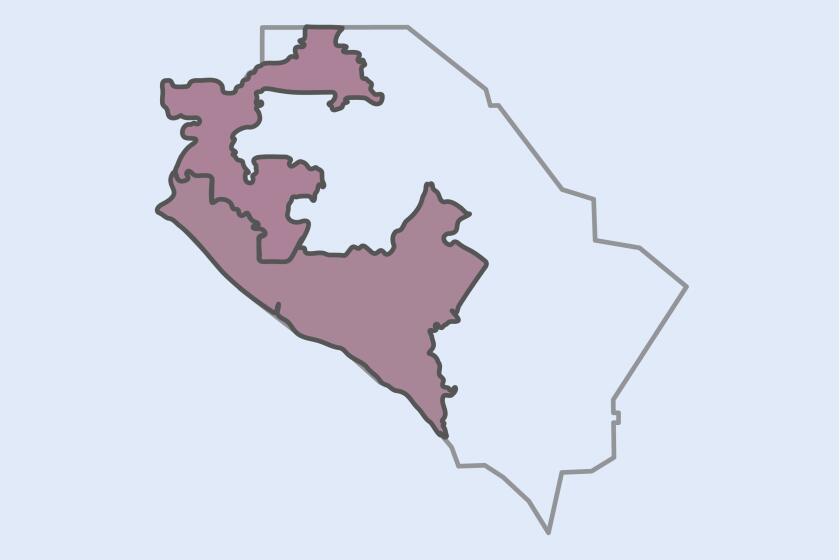

This is no trivial development. The fast-growing eight-county region -- bounded by the San Joaquin Delta on the north, the Tehachapis on the south, the Sierra Nevada on the east and the Coast Range on the west -- is home to more than 3.3 million residents, greater than the population of 21 states. Fresno’s population is larger than that of Miami or Minneapolis. As the region grows, so will its electoral clout.

Although the valley’s realignment has been fueled in part by the arrival of newcomers from other parts of the state and elsewhere, it also has deep historical roots. Valley politics have long been shaped by the great migration from Arkansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and Texas in the 1930s and ‘40s. These migrants brought the politics of their home states with them -- culturally conservative but solidly Democrat. As Southern and border states have turned Republican, so has the San Joaquin Valley.

The valley’s shift to the Republican Party has further widened the state’s east-west partisan divide, with the coastal region ever more Democratic and its inland areas more Republican.

The results of recent elections illustrate these regional trends. For years, the percentage of the San Joaquin Valley’s vote for top-of-ticket candidates -- governor and president -- almost matched that of the state as a whole. But in 2004, President Bush won only 45% of California’s statewide vote but 61% in the valley.

Yet the GOP has not fully capitalized on its growing regional strength because it has failed to strongly compete for several valley legislative seats. The reason, in part, can be traced to another important regional trend: the rapid growth of the Latino population.

From 1980 to 2000, the number of Latinos living in the valley increased by more than 825,000 -- by nearly 500,000 in the 1990s alone -- according to census data. During this period, Latinos accounted for nearly two-thirds of the overall population growth.

These Latinos have not yet fully translated their increased numbers into greater political power because, as in other parts of California, they have registered and voted at low levels. In 2000, Latinos constituted 22% of the region’s registered voters, though they represented about 40% of its population.

But in the valley’s legislative districts, Latinos have achieved more influence because of U.S. Supreme Court decisions requiring states to apportion legislative seats without regard to citizenship, registration or voting, and because of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965, which requires California to draw district lines in ways that protect Latino voting strength.

As a result, in the 2001 redistricting, the Legislature created three majority-Latino districts (Assembly Districts 30 and 31 and Senate District 16) and one (Assembly District 17) that is nearly so. These make up the core of Democratic strength in the San Joaquin Valley as well as an apparent barrier to further Republican gains. Indeed, in the 2006 elections, the GOP didn’t even field a candidate in two races.

But these are precisely the kinds of seats that Republicans need to learn to win.

Although nominally Democratic, the Latino districts are more conservative than most in California. All four strongly supported the 2003 recall of Democratic Gov. Gray Davis and narrowly split in the 2004 contest between Bush and Sen. John F. Kerry. One of the districts, though represented in the Legislature by a Democrat, voted 56.9% for Bush.

The Latino districts also have frequently voted conservative on statewide ballot measures. In 2004, they opposed Proposition 66, which would have weakened the state’s “three-strikes” law, and, a year later, they overwhelmingly supported a proposition requiring parental notification by minors seeking abortions.

The GOP’s lapses in these San Joaquin Valley Latino districts are part and parcel of its broader failure to appeal to Latinos in California. Too often the party has shown indifference to the state’s growing Latino population and has not nominated strong Latino candidates for office.

To increase its chances of becoming the party of choice for California’s emerging Latino majority, the GOP should begin by recruiting conservative Latino candidates to run in the San Joaquin Valley.

If elected, this new generation of Latino Republicans could form a pool of candidates for statewide office.

If Republicans don’t pick up this challenge, they will throw away their regional gains in places such as the San Joaquin Valley and face another decade of tough times at the polls.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.