The spy, the piano man and a fateful cup

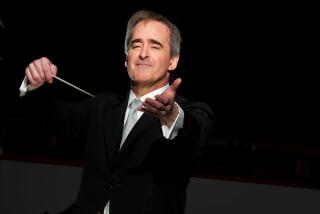

LONDON — One night a little over a year ago, Derek Conlon showed up as usual for his gig as the piano player at the Pine Bar in Mayfair. Sat down at one of the tables for a cup of coffee. Chatted with the barman, stretched, strolled over and started tickling the keys.

That cup of coffee has given him countless sleepless nights since.

Not long after, Conlon, an Irishman known for his ability to glide from Elton John to Frank Sinatra with ease, learned that the table had been occupied moments before by Alexander Litvinenko, the former Russian spy who died after drinking tea laced with radioactive polonium-210.

It got worse: Even though it had been through the dishwasher, Conlon’s coffee cup had also held Litvinenko’s tea.

“My jacket, my piano, my P.A. system, everything I sing through was contaminated. I had people from the Health Protection Agency with Geiger counters in white suits going through my house. All the neighbors were saying, ‘What’s going on?’ ” said Conlon, 44, who was diagnosed with a significant, but not necessarily health-threatening, exposure to polonium.

On the one-year anniversary of Litvinenko’s death on Nov. 23, the Russian’s family and friends traveled to the hospital where he had lain with his internal organs melting for nearly a month, and to the vine-covered Victorian cemetery in North London where he was finally buried in a lead-lined coffin.

They repeated their accusations against the government of Russian President Vladimir V. Putin, which they believe may have supplied the polonium used to kill Litvinenko as punishment for his repeated criticism.

But while the former agent’s death has played out in high-profile international criminal investigations and tit-for-tat diplomatic expulsions between Britain and Russia, the 17 cases of collateral damage such as Conlon have gone largely unremarked.

Those cases include Litvinenko’s widow, Marina, employees at the bar and healthcare workers at the hospital where he died. All 17 people received doses of polonium high enough to pose a potential, if faint, threat to their long-term health, the British Health Protection Agency says.

Conlon has come to look at his life in terms of what happened before, and what happened after, the night he sat at a table just vacated by Litvinenko.

The settled, easygoing musician became anxious, afflicted with high blood pressure and subject to frequent “panic attacks.” Convinced that no one wanted him in the bar anymore, Conlon quit his job and moved briefly to the Caribbean.

There, he said, he began writing songs, and some of them seemed to strike a chord with others. His “A Sad and Lonely Man,” which recounts a man “walking the streets at night, . . . no better place to be,” was a runner-up in the jazz and blues category in this year’s UK Songwriting Contest.

It all began with the news that Litvinenko had been fatally poisoned with a radioactive isotope, and the investigation began to zero in on the places he had spent his last hours before falling ill, Conlon said in an interview at the Piano Bar in Kensington, a small, second-story lounge where he now plays two nights a week.

‘What’s the bottom line?’

“They said they would like me to have some tests,” Conlon recalled. He submitted a urine sample, and was called back a week later to the hotel, where several doctors were waiting.

“The doctor was frowning. He said, ‘Come with us.’ I said, ‘This looks a bit serious,’ ” he remembered. “He said, ‘I’ve got a little bit of bad news: Your test results are a little bit high, of some concern.’ They started to explain a thing called millisieverts. From 1 to 10 is low, from tens to hundreds is a concern. I had 40.”

They wanted him to report to the hospital for more tests. “Finally, I said, ‘What’s the bottom line, basically?’ They said, ‘Short term, you should be fine. Long term, you’ve got a one in four chance of cancer” -- very slightly above the risk most people have of developing the disease, but enough to give him and everyone around him a substantial scare.

“They’re checking my blood, checking my eyes. ‘How do you feel when you sneeze?’ they ask me. And you say, ‘Oh, I’ve got a pain.’ You just start thinking all these things. And people start saying, ‘Is it safe to be around you? Are you OK?’

“I’m terrible, I shake hands with people all the time, it’s part of my job, and people would just pull their hand away, there’s that split second when you’re looking at them. . . . I said to myself, ‘Let’s just try and get by this bit.’ ”

The Pine Bar had reopened in another part of the Millennium Hotel, and Conlon continued to play there, but he and everyone around had trouble putting the case behind them.

“People were not wanting to come in the bar,” he said. “I just felt I couldn’t work there anymore. I thought maybe I ought to change my environment, but that’s easier said than done. I mean, there’s not many piano bars in town, and you feel self-conscious. Will they have me here? Or are they thinking the same thing everybody else is thinking?”

Caribbean revival

When a job opened up in Barbados, Conlon grabbed it.

“I got as far away as I could. And in two weeks of having a great time, forgetting everything, I started edging back again. Much more relaxed. Caribbean life, if you can’t chill out there, you’ve got serious problems,” he said.

He started to write songs. Someone talked him into entering “A Sad and Lonely Man” into the UK Songwriting Contest, and it’s gotten airplay all over Britain.

He resurrected some songs he wrote a few years ago with country singer LeAnn Rimes’ collaborator Ron Grimes for an album, which will be released on iTunes this month; he recently returned from performance tours in Germany and Belgium.

“I’m songwriting all the time now,” he said. “It’s just taken off. What I say is, another door has opened. It was kind of like from the bad, you always look for the positive, and this was the positive. It was recognition of something.”

Polonium’s biological half-life is 50 days, and he expects the results of his third test, to be completed soon, will show that the poison has all but disappeared from his body.

“It is a tragedy, but it’s not like I lost a husband,” Conlon said. “I was unfortunately in the wrong place at the wrong time. But it didn’t kill me. And you’ve got to kind of every day just do everything you can do, you know?”

And whatever you do, don’t shoot the piano player.

--

Listen to Derek Conlon’s music at latimes.com/pianist.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.