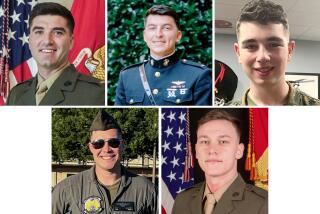

Marine Cpl. Sean A. Stokes, 24, Auburn; killed by improvised explosive

- Share via

Cpl. Sean Stokes was a black-haired, blue-eyed warrior, a fierce and accomplished fighter who dispatched enemies -- one of them by hand -- in three tours of duty with the Marine Corps in Iraq.

His loyalty and love he saved for his comrades-in-arms and for his fiancee, a Marine sergeant who knows how the two halves of his life came together.

“That’s what’s funny, how they coexist,” said Sgt. Nicole C. Besier. “What I loved the most was the way he left his combat boots and boxing gloves and pride at the door, and I saw Sean. Around me, he didn’t have to be that tough guy, he didn’t have to be that hero.”

A native of Auburn, Calif., near Sacramento, Stokes told his father, Gary, after the Sept. 11 attacks that he wanted to enlist and serve his country. He did not come from soldierly stock; a grandfather, an immigrant from Italy and hotel barber, once cut Richard Nixon’s hair.

Stokes’ father refused to give his permission. Five months later, Stokes turned 18 and enlisted without it.

Within a year, he seemed to have fumbled his chance. He went AWOL, then admitted to more unsoldierly conduct.

Stokes “could/should have been booted out,” one of his commanders, Maj. Kevin M. Gonzalez, has written. Stokes begged to stay in the Corps.

The Marines relented and Stokes “quickly became focused and determined. His performances over the next two deployment[s] were amazing. In Fallouja alone, he single-handedly took out 9 insurgents,” Gonzalez wrote.

Through battlefield promotions, Stokes regained the rank he had lost stateside. He caught the eye of more than one journalist; he became a central figure in a book, “We Were One: Shoulder to Shoulder With The Marines Who Took Fallujah,” by Patrick O’Donnell, a historian who was embedded with Stokes’ unit. By the end of the battle, Stokes’ platoon had been reduced to 14 from 46. Every member, O’Donnell said, won a Purple Heart. In that company, Stokes stood out.

“He was a natural leader. He was totally selfless. He was always the point man in the squad. He was the first man through every door,” said O’Donnell, who described Stokes as “100% hero” in a campaign in which “everything was up close and personal -- you killed at six feet.”

Comrades told of how his platoon had cleared an entire house except for one room, guarded by an ominous metal door. Stokes went first. He was thrown back by the concussion of grenades tossed out by the Chechen jihadists inside. He returned fire until others came up and the insurgents were wiped out.

His commanders and fiancee said he was wounded repeatedly but declined to leave the fighting. A superior ordered him evacuated to a field hospital, from which he promptly fled to rejoin his comrades in the battle.

“My medal was just living,” O’Donnell said Stokes told him.

When he heard that his platoon had been tapped for a third tour of duty in Iraq, he asked his old superior, Lt. Jeff Sommers, how he could go with them rather than leave the Corps, as he had been scheduled to do.

“I told him that he didn’t need to deploy again; he’d earned the rank no one told him he could, fought in the biggest battle in decades, and had a good life waiting for him,” Sommers said. “He persisted.”

Stokes got an extension of his enlistment. On July 30, he was killed near Fallouja, west of Baghdad, while investigating a site where an improvised explosive had detonated the day before. He was 24. Stokes was assigned to the 3rd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, 1st Marine Expeditionary Force at Camp Pendleton.

“He not only died for us, so we can live a free and comfortable life, but he also died for his brother Marines,” said Matthew Wise, Stokes’ best friend back home and a fellow football player at Bear River High. “He did not have to go, but he did because he said he wouldn’t be able to live with himself if something happened and he wasn’t with them.”

O’Donnell said he learned that the explosion that killed Stokes came from two 150-millimeter shells that had been rigged to explode when a pressure plate was stepped on. He never regained consciousness. The trap is called a “daisy chain” IED, in which the first blast triggers a second. Stokes caught the initial blast, and his closest friend in the Corps, Sgt. Bradley Adams, the one that followed.

“When the first blast went off, I got up and started running around,” said Adams, speaking from the National Naval Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., where he is recovering. “I was screaming out his name. I finally found him and collapsed next to him.”

Stokes’ fiancee, Besier, said she wants “to be the type of Marine he was. How proud I was to have him in my life. He taught me to love, and that happiness is to love and be loved.”

The couple had agreed that if they ever had children, they would name their first son for Stokes’ grandfather Panfilo Ventresca, who immigrated from Italy’s Abruzzi region, where he grew up with Muslims.

In addition to his father and grandfather, Stokes is survived by his stepmother, Sue Stokes; a brother, Kevin; and his grandmother Flora Ventresca

Gary Stokes said he plans to start a relief fund for the parents of war dead. Contributions to the Sean A. Stokes Memorial Fund may be sent c/o Placer Sierra Bank, 2995 Grass Valley Highway, Auburn, CA 95603.

--