Weave of an artist’s life

- Share via

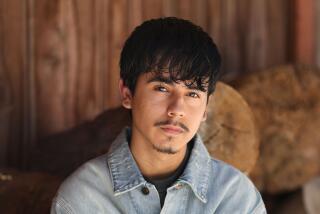

CHIMAYO, N.M. -- As a boy in a tiny village long known for its weaving, Irvin Trujillo remembers being surrounded by the traditional art -- and sometimes nearly smothered by it.

He and his cousins would spend cold winter nights at the little adobe house of their grandmother huddled on a mattress on the floor. His aunt would head to a crib in the back room stacked full of heavy, hand-spun “frazadas” made by his grandparents, he recalls. “She’d come and put these 10-pound blankets on top of us, to where you couldn’t move,” said Trujillo, the seventh generation in a family of weavers and farmers in this valley north of Santa Fe.

Trujillo came to value weaving not only as a legacy of his Spanish ancestors -- who made their way north into the “Kingdom of New Mexico” accompanied by herds of churro sheep -- but as a way to make a living and raise a family without having to leave home.

One of 12 recipients of this year’s National Heritage Fellowship Awards -- the nation’s highest honor in folk and traditional arts -- Trujillo will be recognized at ceremonies Sept. 18-20 in Washington, D.C.

Artistic excellence is a primary criterion for winning a heritage fellowship, and Trujillo’s work is “spectacular,” according to Barry Bergey, director of folk and traditional arts for the National Endowment for the Arts. Artists are selected because they not only respect and build on their traditions but contribute to creativity within them.

“He’s an innovator on tradition. . . . In Chimayo, there were traditional designs that were handed down through the family, but Irvin also uses new images in his rugs,” Bergey said.

Trujillo already has plans for his $20,000 stipend: “Fix the roof on the studio, fix my tractor and put money in for the kids’ college fund.” He and his wife, Lisa, also a weaver, live with their 16-year-old son and 14-year-old daughter on 10 acres, including an orchard, that has been in his family for hundreds of years.

“Weaving was more of a winter occupation, and farming during the summer,” Trujillo said.

He was 10 when he first tried weaving, lured by the clackety-clack of the loom set up by his father, master weaver Jacobo Ortega Trujillo, in the family’s small duplex in nearby Los Alamos.

The elder Trujillo, who had taught weaving for the Works Progress Administration during the Depression, moved to the laboratory town to work after World War II, although the family returned to Chimayo on weekends. Young Irvin quickly discovered he could make money selling small pieces at craft fairs and at a Chimayo weaving shop. But the attraction was more than that.

“It was fun to do. . . . I’ve played drums since I was 8, and it’s very much like rhythm: It has a lot of counting, repetitive counting. And colors. . . . Color is a blast to work with. My dad said color is the most important part of the piece.”

He got a degree in civil engineering and worked for a while for the Army Corps of Engineers, but in 1982, Trujillo, his wife and father opened Centinela Traditional Arts. The elder Trujillo died in 1990. The gallery features the large, bold rugs done by the couple as well as hand-woven wool products by at least 16 other weavers. Centinela is also known for its custom textiles, including upholstery materials.

“For me to sit at a desk, I would go crazy,” said Trujillo, a soft-spoken and modest 52-year-old who is a drummer with a local rhythm-and-blues band. He said he has attention deficit disorder, and the weaving helps. “You have to hyperfocus, which is good for an ADD person. I can’t really think about how I have to go cut the grass, or something like that. . . . I have to really focus.”

Trujillo thoroughly researched his heritage in the Rio Grande tradition of Hispanic weaving.

“I was told I was a seventh generation, and I wanted to know what earlier generations did . . . to know it inside and out.”

And then he went beyond it. He became known for his use of natural, rather than commercial, dyes, for example, and for designs and materials that are not part of traditional Hispanic weaving.

His goal now: “To get pieces in the Louvre.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.