Delta, land of sweet misery

- Share via

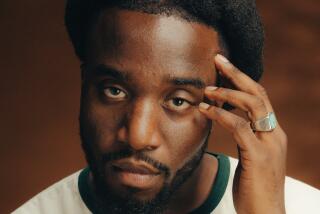

Clarksdale, Miss. — “SOME call it boogie-woogie, some call it blues; I got my rhythm from a fox-trotting mule!” croons James “Super Chikan” Johnson as his golden retriever twirls between his stomping feet, howling right along.

Super Chikan winces with the ecstasy of every note as he puts the hurt on his new slide guitar. This isn’t just any guitar; it’s an electric “Chikantar” he built himself, using a cigar box for the body, a muffler bracket for a tailpiece, a screen door handle for a bridge, an ax handle for the neck, a piece of cyclone fence for reinforcement and a cabinet door latch for a nut. And, of course, his trademark rooster head is carved into the end.

The instruments double as folk art on which Johnson paints scenes of his native Mississippi Delta, and they have made some scenes themselves, including the Delta’s largest blues festival. “Man, I tore that audience up at the Sunflower Festival last summer,” he said. “Dude who was headlining after me got up in a rage, said I didn’t leave nothing left for him.”

Johnson is sitting in his Clarksdale studio just down the road from the crossroads of two highways -- U.S. 49 and U.S. 61 -- the solar plexus of blues traveling, where legend has it that another bluesman, Robert Johnson, sold his soul to the devil so he could play this music.

From Robert Johnson and others, a tradition spread that has made this landscape world famous. Super Chikan’s unique sound is yet another thing that Chicago and Memphis, Tenn., will never have. Nor will New Orleans, on whose streets the other true American art form, jazz, was born.

In fact, my friend Ellen and I drove five hours from the Big Easy, searching for the roots to the blues. We found them within an hour of Clarksdale, this northernmost focal point of the Delta. Our blues tour was a weekend getaway, one full of warm smiles, good food and Southern hospitality.

Like Chikantars, which are mostly made from scrap, the blues -- came from what few things people had.

“I started out with nothing and still got a whole lot of it left,” Super Chikan says. “Heck, got a master’s degree in being poor and broke.

“I’m left-handed, left-footed, left-brained and left out,” he says. A couple of bulbs dangle from his low studio ceiling, where late afternoon sheds blue light through the three small windows. Innumerable paint tubes, brushes, power tools and wrenches are strewn about.

He runs his hand over his latest Chikantar, a portrait of Robert Johnson freshly dried on its front. Like Johnson, Chikan is on the verge of becoming one of the rare Delta musicians to get the credit they deserve. “Fixin’ to take this one to Japan,” he says, beaming.

“The governor and I are goin’ to represent Mississippi.”

I ask how long he’s been playing.

“Oh, not too long,” he says with a sigh. “About 100 years.”

One hundred years ago and 15 miles south, composer W.C. Handy was sitting at a train depot and heard a man playing a guitar: “His clothes were rags; his feet peeped out of his shoes. His face had on it some of the sadness of ages.... [It was] the weirdest music I had ever heard.” No one knows who the guitarist was, but Handy put a color to the sound, and the “blues” was born.

A rich land

THE Delta, which historian James Cobb dubbed “the most Southern place on Earth,” is a 7,600-square-mile region of northwestern Mississippi. It begins 400 miles north of the actual Mississippi River delta. Before the levee was built, the river flooded here, forming an alluvial plain of black earth, one of the world’s most fertile regions. And it’s so flat that the only hills here are Indian burial mounds.

Fertile ground for both crop and creativity, it has arguably produced more music and literature than any other landscape in our country. Besides giving birth to the blues, it has produced myriad writers, including Tennessee Williams, Walker Percy and Donna Tartt. King cotton made a few rich and enslaved the poor. But letters and musical notes came free to all.

And it looks like they’ll be coming for a while longer.

From Super Chikan’s, we head over to actor Morgan Freeman’s club, Ground Zero, also in Clarksdale. A Wednesday-night smattering of locals and tourists pounds pool balls, the dance floor, catfish and cocktails in the warehouse-size venue decorated with Christmas lights and graffiti.

Sitting alone at his own table -- a domain Freeman set aside for him -- is a fellow called Puttin’. As far as anyone knows, that’s the only name he has. There he sits with his deck of cards, waiting to gain the confidence of his next victim using a scheme called the three-card monte.

After Ellen and I graciously lose a few bucks, we hit the dance floor.

It’s open-mike night, hosted by Homemade Jamz, a band that boasts of once opening for Super Chikan. The oldest member is 13, but “Can they jam!” says a man old enough to be their grandfather.

With his red cap pulled low and his smile spread wide, Foster Wiley cleans up empty beer bottles and plates between songs and, an hour later, walks onstage, throws a guitar on and sings the evening’s last song.

“Every night here I clean up the show,” he tells me afterward, between sips of Budweiser. “They call me ‘Mr. Tater the Music Maker.’ ”

Outside, sun-stained and weathered couches sprawl on Ground Zero’s massive porch. Young couples linger on them, sipping beer, smoking cigarettes, trading tales.

Like most things in the Delta, these couches -- and the graffiti, Christmas lights and even Puttin’ the card shark -- were not put here to look cool. They were just put here.

At Cat Head records the next day, Roger Stolle stands in front of his massive chalkboard filled with up-to-the-minute music listings for the dozens of joints spread over the Delta. Be forewarned: None has shows every night, so you need to first visit the shop in Clarksdale or Stolle’s site (www.cathead.biz).

The store is a fantasy of music, books, videos, collectibles, folk art and Super Chikan guitars, all of it somehow shining in the rainy-day gray that washes through the storefront windows and casts a sparkle upon Stolle’s black-rimmed glasses.

While a musician stops in for free coffee, a music video scout grills Stolle for possible shooting locations. After seven years of Delta voyages, Stolle and his wife, Jennifer, dropped their marketing careers in St. Louis to start this place.

“It’s the kind of store we always dreamed of finding in our Delta travels but never did,” he says.

And now he’s organizing the kind of festival he always dreamed of. The third annual Juke Joint Fest will fill 10 clubs on April 14.

“And there’s plenty of other stuff too,” he says. “Like pig racing. You can even sponsor a pig. They’re called the Pudding Porkers, and they race for an Oreo. You wouldn’t believe what I’ve seen a pig do for an Oreo.”

Heading south out of Clarksdale, we cruise through Dockery Farms, where Howlin’ Wolf, Willie Brown and Charlie Patton -- whose hands and voice started it all -- once entertained families who worked alongside them here. Then we hit Itta Bena, where B.B. King was born, and Indianola, where he played street corners and still plays at his Club Ebony at least once a year.

We take some frail, forgotten highway west to the Mississippi, hug its levee north until we find Stovall Farms. As purple dragonflies skitter through dying afternoon heat, we stand gazing into the field where Muddy Waters once drove a tractor for 22 1/2 cents an hour.

Beneath a sky of lavender-tinged clouds lie shallow seas of cotton, soybeans, rice and milo to every end of the Earth, only blackbirds skimming the calm surface, their calls and responses lacing through those of crickets and cicadas.

Before mechanization, men and women worked this land, filling these fields with the calls and responses of their labor songs, a rhythm that stayed with them after they had plucked cotton through the day and begun plucking guitars at night. And, in turn, some were plucked from poverty and gave birth to an American art form that has influenced, whether they know it or not, every kid who has ever picked up a guitar in the last 50 years.

Singing the blues

WE roll into Hopson Plantation as the evening sun goes down and the barbecue’s up. Bluesman Pinetop Perkins, the Grammy-winning 92-year-old pianist, is heating up Hopson’s commissary-cum-juke joint.

Jody the bartender tells us about some of the older musicians still scattered about the Delta, including her friend Jessie Mae Hemphill, a W.C. Handy Blues Award winner.

When the show’s over, we head 30 miles south to Po’ Monkey’s club. There’s no town, no traffic lights, just stars and a dirt road until we see the Christmas-lights-draped shack rising from cotton.

The handwritten sign outside says: “NO RAP MUSIC, JUST BLUES AND OLDEST.”

A giant fan pushes heat and bugs outside. Our eyes and ears adjust to the closeness and darkness. Anything and everything, from disco balls to baby dolls, hangs from the ceiling and walls.

Tonight, Cadillac John’s playing to raise burial expenses for his son. Talk about the blues. They’re so palpable you could swallow the color. And yet sorrow expressed yields joy. It’s all smiles here.

Willie “Po’ Monkey” Seaberry’s grin blows his cheeks up like softballs. He sits, sipping Gatorade, surveying his domain. College kids, musicians and farmers jam the tables and dance floor as Seaberry’s sister sells $1.50 beers and soda out of his kitchen refrigerator.

“So why do they call you Po’ Monkey?” I ask him.

“Cause I’m a po’ monkey!”

Seaberry just slaps me on the back, offers me the grand tour of his home. The only room that isn’t part of his club is his bedroom -- a mattress squashed flush between walls coated with old suits and hats -- which shares a wall with the dance floor.

“I’s up till 3 a.m. last night running the club,” he says with a sigh. “Got on my tractor 6 a.m. this morning, drove two miles to the field I work, then back here to open the place again tonight.”

He smiles a smile that should someday make its way onto a Chikantar and says, “This is not some House of Blues. It’s the house of blues.”

To listen to samples of Super Chikan and other blues musicians, go to latimes.com/blues.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

Southern comforts

GETTING THERE:

Clarksdale, Greenwood, and Greenville, about 50 miles apart, are the three corners of the triangle that make up the heart of the Delta. The nearest major airport is Memphis, Tenn., a little more than an hour’s drive from Clarksdale. From LAX, Northwest offers nonstop service. Continental, Northwest, US, Delta and American offer connecting service (change of planes). Restricted round-trip fares begin at $218.

WHERE TO STAY:

Shack Up Inn, 1 Commissary Circle, Clarksdale; (662) 624-8329, www.shackupinn.com. Here, B&B; means “Bed & Beer.” Seven authentic sharecropper shacks and 12 more rooms in an old cotton gin, refurnished with all of yesterday’s rustic charm and today’s amenities. Double rooms from $50.

The Alluvian, 318 Howard St., Greenwood; (866) 600-5201, www.thealluvian.com. Swank cosmopolitan hotel. Blues tour packages available. Doubles from $175.

WHERE TO EAT:

Doe’s Eat Place, 502 Nelson, Greenville; (662) 334-3315. Dinner nightly. Entrees from $19. The most renowned eatery in the Delta. Amazing grilled shrimp and sopping slabs of steak half falling off mismatched china plates.

Abe’s BBQ, 616 State St., Clarksdale; (662) 624-9947. Lunch and dinner at the crossroads. Best barbecue in the Delta. Sandwiches from $3.50.

WHERE TO LISTEN:

Po Monkey’s, on Pemble Road one mile north of Merigold, 30 miles south of Clarksdale on U.S. 61. Go west a mile when you see the little green “Pemble” street sign on 61. Check www.cathead.biz for a schedule.

Bourbon Mall, Old Tribett Road, Bourbon; (662) 686-4389. “You don’t need no teeth to eat our beef!” is the slogan of this juke joint gem. Music and dinner, Mondays through Saturdays. Entrees from $15.

Ground Zero, 0 Blues Alley, Clarksdale; (662) 621-9009, www.groundzerobluesclub.com. Morgan Freeman’s juke joint, next door to the Delta Blues Museum. Dinner and live music Wednesdays through Saturdays. Burgers and catfish from $4.95. Cover charge from $5.

Club Ebony, 404 Hannah Ave., Indianola; (662) 887-9915. B.B. King still plays here once a year after his September festival. Live music Sundays. $2 cover before 8 p.m., $3 after.

Cat Head records, 252 Delta Ave., Clarksdale; (662) 624-5992, www.cathead.biz/livemusic.html. Up-to-the-minute music listings and festivals.

-- Joshua Clark

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.