With No Tests, Will Results Be Explosive?

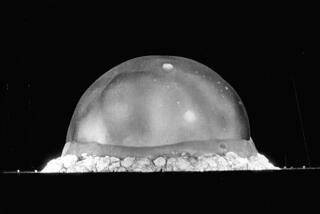

How can scientists be sure that a newly designed hydrogen bomb would work if they never get to test it?

The planned “reliable replacement warhead” is not supposed to ever be tested.

The U.S. halted underground nuclear testing in 1992.

So teams of physicists, chemists and engineers at Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore national laboratories are using supercomputers and scientific instruments developed in recent years to better understand nuclear detonation. But some uncertainties remain.

To address those, they use a complex method to certify that the weapons will work in the event a nuclear attack is ordered by the president.

The method, developed by Bruce Goodwin, Livermore’s associate director for nuclear weapons, is a highly technical system known as “quantification of margins and uncertainties.”

QMU tries to estimate performance margins in a weapon and then make sure that any uncertainties fall within those margins. Proponents say it is a refinement of the basic mathematical method Romans used to ensure the integrity of their bridges 2,000 years ago.

But critics have serious doubts about the process. Is it possible, they ask, to know with any precision the magnitude of what you don’t know?

The Government Accountability Office, an arm of Congress, reviewed that methodology this year and found it had serious defects, including disorganization on the part of government officials overseeing the effort.

Linton F. Brooks, head of the National Nuclear Security Administration, dismisses the criticism.

“Some of what the GAO said made sense,” he said. “But some of it was accountants trying to understand the nuclear weapons design process.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.