A campaign without end

IF you’re a political junkie, Joe Mathews’ book, “The People’s Machine,” will be catnip. If you’re not a political junkie, beware: It could easily make you one.

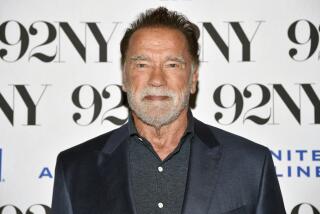

Mathews, a Los Angeles Times reporter who has covered much of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s intense three-year political career -- yes, it’s been only three years -- believes that the governor, in his fusion of entertainment with politics and of conventional government with direct democracy, represents a new phenomenon in American public life.

Except for the labels Mathews uses -- “blockbuster democracy,” “the people’s machine” -- that’s not altogether a new take. A lot of politicians -- Huey P. Long Jr., Fiorello H. LaGuardia, William Jennings Bryan -- put on good shows for “the people.” In our history, a good deal of the nation’s entertainment has come from politicians and preachers. The Romans offered the people bread and circuses.

Nor is Schwarzenegger the first California politician to use ballot measures as part of his political strategy. Republican Gov. Pete Wilson’s reelection in 1994 owed a great deal to his embrace of hot-button crime and immigration initiatives. Jerry Brown, now the Democratic candidate for attorney general, is still trumpeting his authorship of the California Political Reform Act, which helped carry him to victory in the governor’s race in 1974.

But Mathews is right that no one has built ballot measures -- both as instruments of policy and as threats -- into the very essence of governance. The three years have been a nonstop mall-to-mall campaign -- from recall (2003) to recovery bonds (2004) to political reform (2005) to infrastructure bonds, tougher penalties for sex crimes and reelection (2006). Although the governor’s reform agenda famously crashed last year -- some of it before it even reached the ballot -- there’s no sign that his essential approach will change.

As Schwarzenegger, who is as much a Republican maverick as he is a Republican moderate, said after his reform initiatives lost in November, there’s always a new movie. The tough-guy act (“I call them girlie men”) bombed, so now he’s Mr. Nice Guy, as in the early days of his governorship. But blockbuster ballot-box democracy rolls on: politics as shtick. The irony here, as Mathews says, is that Schwarzenegger is trying “to harness California’s century-old system of direct democracy to build precisely the thing it had been designed to counter: a political machine. Of course [this would be] run not on patronage but on stardust.... “

The real appeal of Mathews’ book is in the detailed, sometimes hour-by-hour story that his extensive reporting and proximity to Schwarzenegger’s political operation allow him to tell. It’s a story with a remarkable cast of characters, the 135 candidates hoping to replace Gov. Gray Davis in the recall as well as the old Wilson team -- George Gorton, Bob White, Don Sipple and Wilson himself -- who were waiting for a marketable star like Schwarzenegger.

There is the ever-changing roster of senior staffers -- three finance directors, two chiefs of staff, two communications directors -- plus First Lady Maria Shriver and the Schwarzeneggers’ (and Kennedy family’s) longtime friend, Hollywood lawyer Bonnie Reiss, who’s been a fixture in the administration. There is the ever-shifting list of pollsters, advance people, stage managers, speechwriters, lawyers, publicists and flunkies who keep this show on the road.

Then there are the political negotiating partners: the irascible Democrat John Burton, president pro tem of the state Senate until he was termed out in December 2004, who liked to shoot the breeze with the governor in the smoking tent outside the governor’s office; the muscular prison guards union; and the various Indian casino gaming interests who were “ripping us off.”

And, of course, there’s California Teachers Assn. President Barbara Kerr, who thought she had a deal with Schwarzenegger on school funding during the fiscal drought of 2004, a deal he broke the following year. That break -- and the clumsy way it was handled -- was probably the biggest weapon in the campaign against the governor’s ballot measures in the 2005 election.

Mathews portrays Schwarzenegger as a good listener and quick study. But, like other reporters, he concludes that the governor’s insistence on constant “action” and his overestimation of his ability to sell anything -- especially after his first-year successes passing his $15-billion recovery bond and reforming workers compensation -- led to the confusion of proposals and flawed ballot measures that brought on the disaster of 2005.

Although Mathews doesn’t make a point of it, from the start Schwarzenegger has focused more on process and performance than on the complexities of substantive policy. The misbegotten spending-cap initiative that became the centerpiece of his 2005 reform package was so complex that it probably never had a chance. His merit-pay plan for teachers evolved into a marginal proposal to extend the probationary period for new teachers from two to five years. His pension reform plan flamed out before voters could weigh in.

Schwarzenegger liked to say that if he could sell his bad movies, he could sell anything, but politics isn’t always show biz. With last year’s special election for his initiatives, which took on many of the state’s most powerful interests at once and which could easily be seen as a thinly disguised union-busting strategy, he went to the well once too often. The initiative process, as Mathews says, “was not a magic elixir for politicians to employ whenever they got into jams.”

The fun of this book is its seamless narrative of the Schwarzenegger political operation -- like Theodore H. White’s “The Making of the President” insider’s look -- extended to nonstop campaigning. But it leaves you wishing for more attention to the policies at issue and their larger consequences for the schools, the tax system and for the state as a whole. Ditto for the complex and rapidly changing economic, demographic and social landscape over which Schwarzenegger was elected to preside.

Nor is there much about the opposition. The book implicitly accepts the conventional journalistic wisdom that the Schwarzenegger operation went off track through its own errors, which would be a tribute to Schwarzenegger’s dominance. Gail Kaufman, who ran the well-funded union campaign against Schwarzenegger’s measures, gets little more than a couple of mentions.

It was Kaufman who knew how to exploit Schwarzenegger’s mistakes and who, in a string of powerful TV ads, turned the governor’s attacks on the “special interests” into the faces of individual firefighters, nurses, cops and teachers. Public employees, nurses in particular, showed up to picket and heckle at almost every Schwarzenegger event -- to the point where the governor had to sneak through back doors and garage entrances to get into the hotel ballrooms where he held his fundraisers. How was all that opposition organized and who organized it? Mathews doesn’t tell us.

In contrast with other observers, Mathews believes that it was Schwarzenegger who pushed hardest for last year’s ill-fated special election campaign, that his consultants urged caution. But the political consultants were the most obvious beneficiaries. Did they really want to lose all those fees? Schwarzenegger paid his campaign consultants about $14.7 million between 2003 and 2006, according to the best estimates. Mathews might have noted that even if they were voices of caution, they made out like bandits.

But Mathews’ engrossing narrative of Schwarzenegger’s perpetual campaign is dead-on. The approach worked against a crippled unpopular governor in the recall and through much of 2004, when he had lots of support from prominent Democrats. But when his 2005 initiatives were sinking in the polls, “Schwarzenegger leaned harder than ever on theatrics, [believing] that bigger, flashier events would give him a better chance of pulling out of his rut.” As they say in sports, he stayed with the strategy that got him there.

Yet even Schwarzenegger couldn’t roll his machine over opponents who could outspend, out-strategize and, finally, out-think him -- and who just might have been better on the issues. Blockbuster democracy may or may not survive Schwarzenegger. Either way, however, Mathews’ story will be essential in explaining why.

*

Going to school

An adapted excerpt of “The People’s Machine” that describes Gov. Schwarzenegger’s battle with the teachers union appears on Page 21 of West magazine.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.