Stepping back to see the magic of tap

- Share via

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED tap the way a lot of kids in my neighborhood did in the early ‘70s: through classes offered at a local park. Though great fun -- who doesn’t enjoy making clattering noises with their shoes for hours at a stretch? -- tap felt to me like the less-cultured cousin of ballet, a default dance form for those whose feet could not achieve a proper turnout or go up on pointe (my feet could do neither, of course).

I eventually came to appreciate the subtleties of tap, its exacting rhythms and intimate connections to the jazz it was set to, its surprising sense of narrative. Yet I didn’t quite respect it in the way I respected ballet. Tap was a blast, and therein lay the problem: It was too loose, too easily divined, too eager to please.

Put another way, it was too black. Ballet was lovely, reserved, straight-backed, authoritative -- it was unquestionably white. Politically unformed though I was at 8, I sensed that if I could master ballet instead of tap, I would be in a much better position to succeed in life. Tap was on the ground where I already was. Ballet was up in the clouds, and I concluded that while people on the ground commented on the world -- rhythmically, loudly, passionately -- those higher up actually ran it.

Tap offered spirit to all; ballet offered power to a chosen few. Sure, my classmates and I got hearty applause for performing in silver bowlers and matching cuffs. But the hush that settled over an audience when the advanced ballet groups took the stage and hit their grand jetes was gold.

So I dropped tap and didn’t return to it until I was about 20, when I was actually thinking about pursuing a career in musical theater. By then I had developed a fairly ambivalent take on tap.

On the one hand, I saw it as a precious American art form that was historically undervalued because it was black. On the other hand, I was embarrassed by its close association with vaudeville and minstrelsy and the relentless good-time grinning of tap dancers, even masters such as Bill Robinson and the Nicholas Brothers.

Tap wasn’t serious, which is what I aspired to be. I studied a bit more before leaving it alone -- again.

It wasn’t until 1997 that I came to terms with tap. I discovered a class on the Westside started by Eddie Brown, a legendary black tapper I’d never heard of who’d fallen into obscurity and near-poverty; he taught classes to make money and to keep himself dancing.

Eddie was a rhythm tapper, meaning his style was grounded in improvisation and mid-tempo, complex beats. He wanted to be taken seriously too, and from what I could gather (he died of cancer before I started taking his class) he spent his life proving he was master of an art form that he helped make unique.

As a student of Eddie’s routines, I quickly realized that he wasn’t just commenting, he was creating -- much as George Balanchine created ballets. Nor was his stuff easy. Perfecting a typical Eddie combination required more stamina and muscle control than perfecting a plie or jete. I sometimes got so frustrated I stormed out of class early, vowing once again to never return to tap.

But the magic of the art form -- not its drawback, as I once assumed -- is its accessibility, its standing invitation for anyone with hard-soled shoes and a minimal sense of rhythm to get up and give it a try. Only after you get up do you discover that discipline is mandatory and that exceptional tappers, like exceptional ballet dancers, are rarities.

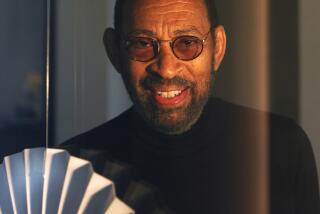

I’m not one of them. I am, however, a true believer in the power of tap. He hardly ran the world, but Eddie Brown had power; so did Fayard Nicholas, the older half of the Nicholas Brothers tap duo who died last week at the age of 91. Fayard was as bubbly and upbeat about his experience in show business as Eddie was unresolved and slightly embittered. Yet both endured racism, which contoured and curtailed their careers, and both prevailed.

Part of what makes tap black, I came to realize, is its extraordinary legacy of perseverance, the ability to exude lightness and grace under a kind of pressure I can only imagine. It’s a legacy I’m still working to live up to, one step at a time.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.