Age Not a Factor

Julio Franco doesn’t understand all the fuss.

He hits one home run, and suddenly everybody he knows is calling. The Hall of Fame is asking for souvenirs. And his feat remains the talk of baseball more than a week later, with everyone marveling at how the “old man” keeps doing it.

“You get tired of the whole subject,” Franco said, “looking at age.”

Although he may not like people going on and on about how old he is -- no, he didn’t wear a flannel uniform -- he’d better get used to it. At 47, he’s defying the aging process, doing things guys half his age can’t manage.

He’s not the only one, either. Look around the majors this first month of the season, and you’ll see plenty of geezers showing up the kids. The boys of this summer have gray in their hair and miles under their belts.

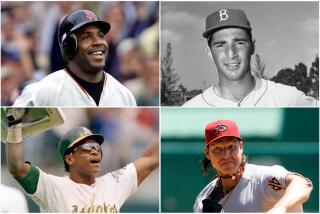

Greg Maddux, who turned the big 4-0 on April 14, has won his first five starts for the first time in his career, and leads the majors with a 1.35 earned-run average. Tom Glavine, also 40, is among the NL leaders in strikeouts. At 43, Jamie Moyer is still good enough to be the Seattle Mariners’ opening-day starter.

Curt Schilling, who doesn’t join the 40 club until Nov. 14, leads the AL in strikeouts, and ranks near the top in innings pitched and ERA.

Three months shy of his 42nd birthday and battling a tender, surgically repaired knee, a swollen left elbow and continuing questions about steroids, Barry Bonds homered twice in as many days this week. That brings him within three of catching Babe Ruth for second place on the all-time home run list.

Steve Finley has three triples with his 41-year-old legs. So does Kenny Lofton, though he’s a relative baby. He’ll be 39 on his next birthday, May 31.

“Just because I’m 40-plus, there’s no one in this game telling me I’ve got to quit,” said Moyer, who has won 205 games in 21 seasons. “As long as I feel like I am able to contribute to building a winning team and I have my health, why not?”

The average major leaguer this year is 29.82 years old, and the Elias Sports Bureau said there are only 17 players who are 40 or over. With 855 players on active rosters or the disabled list, that works out to about 2% of the entire league.

But the old guys are making their numbers felt.

“If you’re physically fit and take care of yourself, you should be better later in your career. I had my best year before I retired,” said Met Manager Willie Randolph, who hit .327 with 54 RBIs in 1991, his second-to-last season in the majors.

“You should get better if you keep yourself in shape and still have passion for the game,” Randolph added. “That’s why you see guys playing longer.”

Still, it’s one thing to be playing in a beer league after you hit 40, and quite another to be competing against the best players in the world, most of whom aren’t even 30.

“It used to really be an anomaly to see a huge population of [older] athletes in any sport,” said William J. Evans, the chief of the Nutrition, Metabolism and Exercise Laboratory at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences.

“Training and nutrition have really helped the older athlete,” added Evans, who also is a research scientist at the VA Medical Center in Little Rock, Ark. “But I think they really have to work hard at it.”

While all older players are blessed with certain genetic gifts that have kept their bodies from breaking down, most say a workout regimen and/or close attention to their diet has enabled them to keep playing long after their contemporaries retired.

Maddux put in extra effort at the gym in the offseason, and he began the season in better shape than he’s been in in years. With Kerry Wood and Mark Prior out indefinitely, he’s become the anchor of the Cubs pitching staff, an ace once again in his 20th season.

Though Moyer said he doesn’t have a special diet, his workout regimen would leave a teenager gasping for breath. He works out for 2 1/2 hours on the day after he pitches, lifting weights, stretching and doing a mix of upper body, cardio and water work. On his other off days, he’ll do leg weights, exercises to strengthen his abdominal muscles, more cardio and then throw a bullpen session.

“It’s my responsibility to me, to my teammates, to the organization,” Moyer said. “It’s hard work, but it’s a simple way of doing it.”

Then there’s the ageless Franco. Though he goes to bed as early as 8 p.m. and has a strict diet that centers on organic foods, he credits his Christian faith for his longevity.

He’s also a fiend when it comes to conditioning, though. He lifts weights and works out year-round.

“He came prepared and he worked hard,” said Maddux, who played with Franco for three seasons in Atlanta. “Here’s the oldest guy on the team in the batting cage, hitting off the tee with one hand, and the young guys are in their underwear playing cards.”

There are some sports where it’s “easier” for older players to excel too. People begin losing their fast-twitch muscle fibers, which produce quick, explosive movement, in their 20s and 30s, Evans said. In speed sports, like football, basketball or tennis, that loss of a step or even half a step can mean the difference between playing and retirement.

But in a highly skilled sport like baseball, where hand-eye coordination is most critical, Evans said players can be successful longer.

Look around any sport, and you’ll find a Franco or two. Karl Malone played until he was 41. Chris Chelios is chasing another Stanley Cup at 44 -- two months after playing for the U.S. team at the Turin Olympics.

Fred Couples came close to winning this year’s Masters at 46, and Washington Redskin offensive lineman Ray Brown finally retired in January at the grand old age of 43. Martina Navratilova is still playing at 49, and has won 10 doubles titles since 2002.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.