Smithsonian-Showtime deal outrages filmmakers

WASHINGTON — As part of a near-exclusive deal with Showtime Networks, the Smithsonian Institution is restricting filmmakers’ access to its scientists and archives, prompting another outcry over the museum’s attempts to make money.

Filmmakers who have relied on the vast holdings of the Smithsonian, and typically pay to use historic film or copy an artifact, have raised objections to the new policy of limited access to the public collections. Now most filmmakers will not be granted in-depth use of Smithsonian materials unless they are creating work for the Smithsonian-Showtime unit.

Such films would be available through the Smithsonian on Demand cable channel to the small fraction of viewers with digital cable -- about 25 million homes.

Jeanny Kim, vice president for media services at Smithsonian Business Ventures, said the filmmakers who were doing “more than an incidental treatment” of a subject mainly from Smithsonian materials or wishing to focus on a Smithsonian curator or scientist would first have to offer the idea to Smithsonian-Showtime. Otherwise, the archives could not be used outside the realm of news programs (such as “60 Minutes” and “Dateline”) in most cases.

The new restrictions have outraged some filmmakers and researchers, who are criticizing the limitations placed on public archives, as well as the Smithsonian’s refusal to reveal the details of its Showtime contract. Inside the institution, some staff raised questions about the lack of consultation regarding the new policy. Others said the change was overdue because the Smithsonian had lacked control over its property.

“I think this is obscene,” said Laurie Kahn-Leavitt, a filmmaker whose award-winning documentary about Tupperware relied heavily on materials at the Smithsonian. “That film would not have been made without the papers of Earl Tupper and Brownie Wise that are at the Smithsonian.”

Kahn-Leavitt added, “I am not against them having a deal with Showtime that is lucrative. But the archives are for the public to use.”

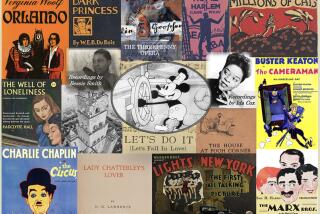

The materials at the Smithsonian cover almost every aspect of American life, from presidents to inventors to musicians to oceanographers to astronauts. Ken Burns mined material at the National Museum of American History for his PBS series “Jazz.” The History Channel included film from the same archive for a program on the Chrysler Building. The Discovery Channel has used aviation footage from the National Air and Space Museum for its programs.

The National Museum of Natural History has an active relationship with filmmakers, who often want materials on such subjects as forensic anthropology, human origins, the Hope diamond and dinosaurs. Last year nearly 500 researchers spent almost 900 days working at the American history museum. That archive receives about 5,000 e-mails a year, from students and professionals, asking about materials to study.

The usual fee for shooting on location at the Smithsonian was about $2,000 a day. “We never got any financial gain from it,” said Linda St. Thomas, the Smithsonian’s director of media relations.

Ellen Rothman, associate director of the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities, which gives start-up funding to filmmakers, said she was “astonished” at the Smithsonian’s treatment of the independent filmmakers. She said the policy would bring additional hardship on documentarians.

“The idea that they wouldn’t have affordable access to a major public repository has implications for their budgets and the stories they can tell,” Rothman said. “It is the first place everybody goes because it is a public source.”

The Smithsonian was looking for a way to develop its own film and television materials, Kim said. One goal is to make sure the public knew that any new films were relying on Smithsonian artifacts and personnel.

The Showtime agreement created a new division, Smithsonian Networks, which will offer film products that would be available on demand to the cable company’s subscribers. The Smithsonian made no investment, museum officials said.

The Smithsonian declined to release the agreement, insisting that the terms are “proprietary.” The deal, which went into effect Jan. 1, was announced March 9; the controversy was first reported on last week by the New York Times. All contracts with filmmakers made before the change are being honored, Kim said. Since the change, 24 of 26 requests have been approved, said David Royle, executive vice president for Smithsonian on Demand. By December, when the new Smithsonian on Demand programming becomes available, 40 hours of it should be available.

The new relationship with the filmmakers has several tiers.

“If the entire subject revolves around the Smithsonian, we would look at it and say maybe we want that for Smithsonian on Demand,” St. Thomas said. “If we do, we would begin hiring producers to put these pieces together. Showtime and the Smithsonian don’t have the staff.”

Requests from scholars, journalists and educators will usually be approved, she said, stressing that news and curriculum programs would have access to the archives.

Royle said he believed the deal would create opportunities, not limit them. “Filmmakers welcome with open arms the opportunity to get funding to make quality filmmaking,” said Royle, a veteran of National Geographic Television and Film. “Whenever you have a change like this, you are going to have a few bumpy moments. This is not a situation where anyone intends to stop people from making great films.”

In recent years, the Smithsonian has signed controversial agreements with donors for large gifts for the restoration of buildings and other needs. In return, it has frequently given the donor a prominent name on a piece of Smithsonian real estate.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.