Justice Is Swift and Deadly in Baghdad

- Share via

BAGHDAD — The blacksmith, the builder and the laborer were sentenced to death just before noon.

The murder victim’s son cried out, “God is great! God is great!” Bowed and unshaven, the murderers were cuffed and quietly led away. Someone said they must be guilty. An innocent man would yell in protest until his voice disappeared.

The trial had lasted two hours. It was the third time since the end of Saddam Hussein’s regime that the death penalty had been handed down.

Iraq is at war and justice is tenuous. The defendants at last week’s trial never met the lawyer who argued their case. They weren’t allowed to introduce medical or other evidence. There was no cross-examination of prosecution witnesses, because there were none. The little testimony given was mainly the denials of the accused.

The men were charged with assassinating a senior intelligence official in the Interior Ministry. The crime occurred about 8 a.m. on April 28, when Gen. Abdulmihsin Ali Abdulsada was driving through the Dora neighborhood of Baghdad on his way to work. A car pulled up beside him near the Al Sadoon mosque. Kalashnikov fire glinted.

The case, its documents held together with straight pins and rubber bands, landed in the 1st Iraqi Central Criminal Court, the former museum where Hussein stacked trophies and gifts from world leaders. A glass spire tapers toward the sky to a round clock whose chimes once echoed over the Tigris River. These days pigeons flap through holes in the glass and glide through the courthouse foyer.

One fluttered in on the opening morning of the trial, as the three accused, Asaad Diafis Abdullah, Ayad Salman Chiad, Mohammed Ali Ghadhban and their alleged accomplice, Hamad Jabar Atiyah, were led from holding cells. They stood outside the courtroom and offered their manacled wrists to the bailiff. Silver shackles clunked on the floor. The men were ordered to turn and face the wall, sitting cross-legged.

Policemen wearing bulletproof vests gathered and shared cigarettes around them. One officer, Ahmed Hashim, said: “Why waste the court’s time and money on these men? We should cut them up and throw away the pieces.”

Ghalib Rubaii sweated in a wrinkled black robe. The homicide lawyer had received a call the night before, the friend-of-a-relative-of-a-friend kind of call coming from a poor street in a mean neighborhood. He would represent the defendants.

“I don’t know all the details,” he said. “I haven’t seen the full case.” When asked if he had met his clients, he said no. He double-checked a piece of paper to remember their names.

The trial would begin in 20 minutes.

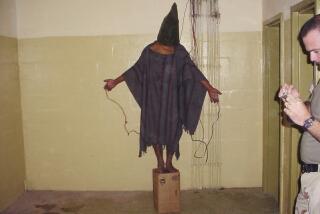

Presiding Judge Luqman Thabit Samiraii prepared papers in his office upstairs. He lives in a tight whirlwind of bodyguards. More than 25 judges have been assassinated in Baghdad since major combat ended in 2003. The case before him represented a complicated intersection of interests. Iraqis live in fear and want murderers executed; the Interior Ministry has lost a prized officer; a son wants vengeance; the defendants have confessed, but said they did so under torture that included rape with a metal rod.

Samiraii acknowledged that there were cases of police brutality. But there is also an insurgent war, tribal blood feuds, suicide bombings and a Baghdad police force of 15,000 that’s half the size of what is needed. In Hussein’s era, the courts did the bidding of the secret police, and in the new Iraq, the courts and police feel the pull of the past as they hand out justice to a nation unaccustomed to democracy.

U.S.-led forces were concerned that Iraq’s death penalty would become a tool of political vendettas and abolished it shortly after occupying the nation in April 2003. As graveyards were widened and bodies were stacked in the hallways of morgues, the new Iraqi government aggressively reinstated the law this spring. Hussein is expected to face execution if convicted in a trial set this summer.

“Only in God can we trust,” Rubaii said as the courtroom doors swung open.

The defendants stood in the dock. Atiyah, a narrow man with bristly gray hair, and Abdullah, a stockier sort, tilted back their heads to see over the wooden railing. Ghadhban and Chiad are taller and younger. Judge Samiraii sat in the big chair in the middle of the bench. A second judge, a man with a polished pate and two pairs of reading glasses, sat to his right, and a third with a heavy face and a blunt mustache whispered from the left.

The accused were called one by one to testify. Shortly before 11 a.m., Judge Samiraii questioned Chiad. At 11:11, the judge turned to Atiyah. At 11:24, he questioned Ghadhban. Abdullah was next at 11:32. The questioning was finished at 11:36.

The defendants said they were welding, plastering and working construction on the morning of the murder. Atiyah, the accused driver of the car, said his brother was a policeman killed by rebels. “How can I cooperate with terrorists?” he said.

He told the judge that the police “tortured me for five days, tore off my clothes and underwear and threatened to rape me and bring my wife and sisters in to rape them.”

“Why did you confess?” the judge asked Abdullah.

“By force and torture,” he said.

The judge looked at Chiad: “An AK-47 was confiscated from your house, and the empty shells [at the murder scene] match your rifle.”

“No. No rifle was taken from me,” Chiad said.

The power in the courthouse, as is common across Iraq, went out at 11:40 a.m. Heat swallowed the last wisp from the air conditioner, the lights died, and bailiffs rushed to open thick green curtains that held back the desert sun. Sunlight filled half the courtroom. Abdullah squinted in the dock. Atiyah rose on his tiptoes as if to say something, but was hushed. A chorus of crinkling sounds drifted over the bench as the judges fanned themselves with paper. There was no cross-examination.

The prosecutor, whose name is being withheld for security reasons, rose. A stooped man with a black robe trimmed in red, he said the defendants had confessed before an investigating magistrate when there were no police around. He added that ballistics tests found that the AK-47 taken from Chiad was the murder weapon. He did not question the defendants. He called for the death penalty and sat down.

Sweat rolled down the faces of the judges, the defendants, the son of the victim and the court stenographer, who wore a head scarf and wrote in longhand. Rubaii wagged his finger at the judges. He said he needed time to collect witnesses, accumulate medical evidence and meet his clients. The second judge changed his glasses and opened a folder. The court granted a two-day postponement and adjourned at 11:57.

Shackled at the ankles and wrists and threaded together, the defendants were marched through the foyer.

Less than 48 hours later, Rubaii, wearing the same gray suit and wrinkled robe, still had not met his clients. “This is a breach of justice,” he said. He added that requests were denied for medical examinations to determine if the defendants had been tortured. But he did round up alibi witnesses. He was confident, too, about a closing statement he had prepared. At 10:34 a.m., his clients were back in the dock.

By 10:59, Judge Samiraii had questioned six witnesses. They were laborers, welders and contractors. Some were relatives. Most were friends. Samiraii didn’t believe them; these kinds of men sometimes also give allegiance to the insurgency.

The judge motioned to Rubaii. The lawyer lifted the pages of his closing statement. It was a flourish of a textured voice, a plea, strings of words and outrage, but little evidence. “Is this the way of handling a case like this?” he asked the court. “Is it good to convict people whose confessions were gotten in such a manner that is counter to our laws?”

He flicked to another page and read on. The prosecutor nodded off for a moment. Rubaii reached the final sentence at 11:17. The judges cleared the courtroom to begin deliberations.

The courtroom doors reopened at 11:36. Rubaii tossed his cigarette on the floor.

“Only in God can we trust,” he said.

Guilty.

Atiyah was given 10 years in prison. The others were sentenced to death by hanging. No execution date was set. Rubaii promised to appeal.

*

Times staff writers Shamil Aziz and Suhail Ahmad contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.