Sit, stay, succeed

- Share via

People rarely leave home thinking they might be hit by a freeway sniper, killed in a car crash or mauled by a mountain lion while riding a bike. Dean Koontz does.

The bestselling author takes no day for granted. For him, suspense is the key element of life. “None of us know what’s going to happen to us later today or tomorrow. We live in a perpetual state of suspense. We live in denial of that, but it’s true.”

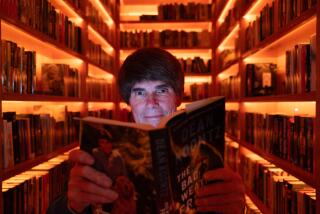

Well, for Koontz it is, which is why he can’t imagine writing anything but the suspense fiction for which he has become so famous. His latest novel, “Life Expectancy,” is full of hair-raising moments, fomented mostly by a homicidal clown who pursues perhaps the most lovably loony fictional family since “Arsenic and Old Lace.”

Then there is Koontz’s Odd Thomas, a small-town fry cook who converses with ghosts and catches killers in a hold-your-breath race with catastrophe. And who could forget Einstein, the genetically altered dog who thinks like a human and battles a monster mutated from a baboon?

What kind of mind invents such off-the-wall creatures and earns multiple millions in the process? Only a slightly eccentric guy like Koontz, 59, who freely admits he has some unusual traits.

His habits verge on obsessive-compulsive, he says with a grin. “It’s a thin line, and I haven’t crossed it -- yet.” This is a guy who hasn’t flown since the ‘70s, who has never been out of the country except for car trips to Mexico and Canada, who almost never takes vacations, and who lives in what he calls an “outrageously indulgent” Newport Coast palace that took him 11 years to build, and that he hates to leave.

“I have this philosophy, which has proved true for me: If you’re observant, any square mile on the face of the Earth will tell you all you need to know about life and people.”

A homebody at heart

He has written 70 books in half as many years, with sales nearing 300 million in 38 languages -- all with little publicity for his books or himself. (“I’m probably the only bestselling author who’s never done a book tour.”) He gets 20,000 fan letters a year, reads every one and employs two full-time assistants to help answer them. He doesn’t use e-mail and has no Internet access on his computer because it might distract him from his work, which he does all day every day, pretty much nonstop.

This is necessary because the man doesn’t just write at a breakneck clip. He edits each page at least 20 to 30 times immediately after writing it. When the chapter is finished, he prints it out and starts editing those same pages all over again. “It’s fun,” he says.

At the moment, he has two titles on bestseller lists: “Odd Thomas” in paperback and “Life Expectancy” in hardcover. A new dog philosophy book, “Life Is Good! Lessons in Joyful Living,” purportedly written by the family dog, is now in its third printing. And his re-imagining of the classic Frankenstein tale comes out today, “Dean Koontz’s Frankenstein: Prodigal Son” (with Kevin J. Anderson).

Koontz is a neat freak whose canine companion, Trixie, is walked for exactly one hour every morning and then brushed for precisely 45 minutes (by Koontz or his wife, Gerda; they alternate days) and then brushed again for 10 minutes every night -- all possibly an effort to prevent even one of her golden hairs from being shed in the spotless Koontz house. It’s spotless because he employs a window washer on his 11-person, full-time staff to polish not just the windows but everything else in sight.

Koontz himself looks vigorously buffed and polished: a compact, wiry man with a friendly face topped by a thatch of vivacious, precision-cut black hair.

More important than all that is Koontz’s unusual mind-set. He seems keenly aware at all times of the randomness of life. Early in his career, he was categorized by his publisher as a horror writer. This wasn’t accurate, he says. He doesn’t write about vampires and werewolves but rather about the sheer suspense of simply living.

Because he’s an optimist, however, he prefers to focus on the flip side of his life-is-suspense philosophy: You can leave home as a lonely pauper and return that night with intimations you’ll find love and riches. He keeps life’s shocks, good and bad, close to the emotional surface, even those that occurred decades ago.

He describes how he finally won a first date (after four rejections) with the woman who has now been his wife for 38 years -- and tells it as if it happened yesterday. “We’ve never not had fun together. The years together seem like no time at all.”

Or when he hit the bestseller lists for the first time years ago. “My publisher called. She said, ‘The good news is that you’ll be No. 1 on the New York Times bestseller list. The bad news is that it’ll never happen again.’ ” Why not?, he asked. “ ‘Because your books aren’t bestseller material,’ ” is what he remembers her saying. He has made the bestseller lists steadily ever since.

Critics have considered much of his work to be lit-lite, although he’s had his share of glowing reviews. USA Today called him “a superb plotter and wordsmith” who “chronicles the hopes and fears of our time.” And his latest, “Life Expectancy,” won a rave from Publishers Weekly, which called him the world’s “most underestimated” bestselling author.

This is nice but probably not terribly crucial at this point in Koontz’s career. He can’t stop writing no matter what critics might say. And he can’t take full credit for what he produces, he says. He sits down at his spotless, burnished-wood desk, in his home office with burnished blond-wood walls, with his view of the canyon and the Pacific beyond, and creation begins.

He doesn’t know how it happens. The clown character in his latest book, for example: “I had no idea the clown was going to be there. I knew something dramatic would happen that would be the source” for the drama that lay ahead. “I described the expectant fathers’ lounge, and I wrote, ‘the ambience wasn’t improved by the angry, chain-smoking ... ‘ and the word ‘clown’ came to me. I typed ‘clown,’ and it stopped me dead. I said, ‘This is absurd. I can’t have the guy be a clown.’ I stared at the word for 15 minutes. Then I thought, ‘Trust your subconscious. It gave you a clown so there must be a reason. Write for a while and see what happens.’ And the more I wrote, the more I loved it.

“It’s like a gift. You know how hard you work. But you also know it takes a confluence of things over which you have no control. I don’t want to sound like Shirley MacLaine or anything, but it’s like [the book] is being channeled to me. But you can’t take the credit. You can’t say, ‘Boy, am I a genius.’ There’s this component to the creative process when the work is really flowing, and you really feel you’re in touch with some higher power.”

Koontz says he’s shunned the “celebrity route” because he has much more in common with the local craftsmen and artisans he’s become friends with, people whose integrity and passion for precision and excellence in what they do seems compatible with his own.

“What I learned some years ago is that people in the trades, like masonry or cabinetmaker or painter, if they are really good at what they do, I recognize immediately their mind-set. It’s the same reason I do 20 or 30 drafts of a page.”

Koontz seems to prize character over almost everything else -- in his writing and his life. Integrity is what draws him to people, he says. The contractor who built his current house, for example, had never built one before. “He had built my pool. I knew his great integrity and strength of character. I could trust him with anything. He had a contractor’s license, so I hired him to do it. People thought I was crazy. But he did a brilliant job.”

Youthful pursuit

Koontz has known since his teens that writing is his calling. His wife, whom he met in high school and married when he was 21 and she was 20, offered to support him for five years while he tried to make it as a writer. She worked in a shoe factory, among other places. “If you can’t make it in five years, you’ll never make it,” she told him. But he made it. At the end of that time, he was earning enough to keep the couple modestly afloat.

At that point, she took over the business end of their lives -- bookkeeping, contracts, bills -- which became increasingly complicated as his work became more popular. She still handles their finances and investments. “It’s a full-time job,” he says.

There were no writers (or even readers) in his family. Born into poverty in a Pennsylvania town of 4,000, he had a sickly mother and a violently abusive, alcoholic father. Hunger and the threat of homelessness were constant. And what home there was, he hated to go to. When he read books, he was told to stop. “Go do something else, like learn to repair cars. How are you going to have a car if you can’t repair it? We can’t afford mechanics in this family.”

Now, his new home with limestone floors and miles of windows has an immense library, the books impeccably aligned in 10-foot-high stacks of the same high-gloss, quarter-cut blond anigre wood that lines his office.

He retells the story of his childhood as if the pain were still present but says he was not an unhappy child. “Those books saved me, transported me to a happier place.” It may sound like the most empty-headed sort of self-help, Koontz says, “but I tell people happiness is a choice. You can choose to be happy. That’s what I did.”

His novels are happy too, in an unexpected way. In his latest, for example, protagonist Tock grows up to meet his soul mate, who gives him three well-loved children for whom both parents would gladly give their lives. At times, it looks as if they might have to. But throughout a years-long series of murderous crises and mysterious events, the Tocks, their little Tocklets, an incomparably zany Grandma Rowena and assorted others all hang together to defeat evil, love one another and have fun.

A dog’s life

The Koontzes have no children. At this point, Trixie may be as close to a daughter as they’ll get. She is their first dog, adopted three years ago from Canine Companions for Independence in Orange County, which is one of their favorite charitable organizations. All proceeds from “Life Lessons!” will go to the group.

Koontz’s warm and funny portrayal of parenthood in “Life Expectancy” is “perhaps a degree of wish-fulfillment,” he says. Though he loves children, he says he and his wife decided against having any at a time when they had taken over support of his destitute father, whose errant ways had gotten worse over the years.

“We took care of him for 14 years. They were years of absolute nightmare. It was like everything bad in my childhood; I’d opened the door to let it back in. But there wasn’t anything else we could do. He was one of five brothers, and I realized they all were the same way.” Alcoholic, suicidal, unemployed. “It was then that I said, ‘Oh, God, I wouldn’t want to subject any child to possibly inheriting that.’ ”

So Trixie lucked out and gets to sleep in her owners’ bed, sit by the author as he writes his bestsellers and nibble on apricot jam-laden crackers offered by Gerda.

The Koontz house, all 25,000 spotless square feet of it, is Trixie’s playground and the culmination of the Koontzes’ dream. Not a McMansion, it’s an elegant, low-slung design (Koontz worked with architects for four years after buying the 2 1/2 acres of land in a gated community). It’s a meld of Art Deco and Asian decor. Antique rugs top the limestone floors; a Han dynasty dog sculpture guards the entrance to the sumptuous guest wing, which has its own sundeck and infinity pool.

Although it had to have cost millions (he won’t discuss money), the Koontz luck still holds.

“We’ve already had calls from people who want to buy it. One guy flew over in a helicopter and contacted us, offering a price that was twice as much as it cost to build.”

The Koontzes aren’t selling.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.