Kidnappings Bleed Iraq of Doctors

- Share via

BAGHDAD — Five months pregnant, Khalida Hussein lies dying in a Baghdad hospital, a malignant brain tumor sapping her ability to walk, eat and speak.

There’s perhaps one doctor in Iraq talented enough to save her life: a neurosurgeon ranked among the best in the Middle East.

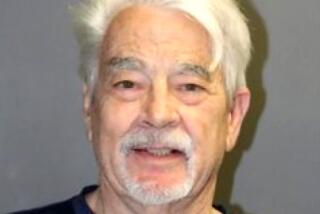

But Dr. Abid Hadi Khalily is holed up in his home, recovering from a traumatic kidnapping in April. Colleagues say he’s too depressed and frightened to return to work and is preparing to leave the country.

For two months, someone has been kidnapping the best doctors in Iraq. Health officials and doctors estimate that as many as 100 surgeons, specialists and general physicians have been abducted from their homes and clinics since the beginning of April. Some were beaten and tortured. Most were released after the payment of between $20,000 and $200,000 in ransom.

Already plagued by outdated equipment and drug shortages, Iraq’s fragile healthcare system is buckling under this new security threat. Some doctors who have not been kidnapped have fled Iraq -- just as the nation most needs their help.

“We are losing the brain power of our most brilliant doctors,” said Dr. Sami Salman, internist and medical director at the Special Care hospital at Baghdad’s Medical City healthcare complex. “You can’t just replace these people overnight.”

Ransom, it seems, is not the only motivation for the crimes. In many cases, abductors have ordered the physicians to leave Iraq, sometimes setting a deadline.

Iraqi officials fear that the abductions and threats are an organized attempt to cripple the country’s healthcare network, likening the tactics to terrorist attacks on the country’s oil pipelines or electricity plants.

“These are not purely thieves,” said Dr. Amir Kuzaii, deputy health minister. “These people have different aims. They are professionals. They want to paralyze the basic functions of the country.”

Interior Minister Samir Shakir Mahmoud Sumaidy has promised to set up a task force to investigate the crimes.

“There is a political component to this,” he said.

But such efforts will do little to help the desperate patients in Khalily’s waiting room. Each day they come and sit, hoping to be treated by the renowned neurosurgeon in case he returns to work.

One patient, a father of 11, suffers from abnormal secretion of growth hormones, which doctors say is causing his brain cells to overproduce. His hands and nose are enlarged, and he suffers from severe headaches. His operation was canceled after the doctor’s kidnapping, and he doesn’t trust anyone else to do it.

“Whoever did this kidnapping hurt me more than they did the doctor,” said Malallah Azeez, 47, a retired military officer.

The husband and brother of Khalida Hussein wait for news of whether another doctor will be willing or able to operate on her brain tumor. Doctors told them Khalily was uniquely qualified for the complicated case.

“They tell me they will do their best,” said her husband, Hartim Makhlif.

The couple lost their first son to leukemia at age 5 last year.

“Now they say I may lose both my wife and my [unborn] son -- again,” he said.

The list of kidnapping victims and those who have fled the country is a who’s who of Iraq’s medical establishment. A pioneer in renal transplants. Saddam Hussein’s former plastic surgeon. And Khalily, who was voted Best Arabic Doctor in 1998 by the Pan Arab Medical Union.

The top cataract surgeon at a leading eye hospital in Baghdad, Dr. Jawad Shakarchi, moved to London after being abducted from his garage in April.

“He was a genius,” said a hospital manager, Amira Salman. “Now his students are doing his job.”

Many of the doctors also taught at Baghdad University’s College of Medicine. Officials there said a quarter of the school’s surgeons have gone or have requested temporary leaves next year.

“A lot of doctors are planning to quit for a year, and we don’t have enough teachers for the clinical studies,” said Dr. Hassan Rubaye, deputy dean of the medical school.

Some schools are having to limit enrollment for advanced studies until they can be sure there will be enough doctors to teach.

Dr. Gayath Tawfiq, an orbital surgeon, was on his way home from work this month when two other vehicles suddenly blocked the road. His driver fled, and a gang of men with machine guns grabbed Tawfiq and his 22-year-old son.

“They hit us with their guns,” Tawfiq said, parting his hair and pulling up a pant leg to reveal bruises that remained two weeks later. His abductors lifted his blindfold just long enough, Tawfiq said, for him to see his son with a rope around his neck. “They told me they would hang him if I didn’t pay,” he said.

After the kidnappers received $70,000, they ordered him to leave the country forever. One of them -- whom Tawfiq was never able to see -- exchanged wristwatches with Tawfiq and threatened to go to his office if he didn’t leave, pretending to be a patient. “You’ll recognize me by the watch,” he told the doctor.

But Tawfiq has not left. “I can’t leave now,” he said with a shrug. “They took all my money.”

As soon as he is able, however, he is planning to move.

By the time kidnappers arrived at Dr. Mothafer Kurkuchi’s clinic, the orthopedic surgeon -- who said he knows dozens of doctors who have been abducted -- was practically expecting them.

“You are welcome to come with us, doctor,” one of the kidnappers said sarcastically. They drove him around for eight hours, he recalled, including two hours in the trunk of the car. He lied and told the men he had no other family, he said, and negotiated the ransom as low as possible. “I know how to deal with Iraqis,” he said.

Afterward, he said he did not bother to report the crime. “What can the police do?” he asked. “Some of them are probably in on it.”

The Iraqi Central Criminal Court is investigating three cases of doctor kidnapping, including one allegedly involving employees of the Iraqi National Congress, the political party founded by controversial Governing Council member Ahmad Chalabi that was once funded by the Pentagon. A recent raid of Chalabi’s home in Baghdad was partly based upon a doctor’s claims that INC employees had apprehended him.

Kurkuchi isn’t optimistic that police will be able to halt the kidnappings. But unlike many of his colleagues, he will not budge.

“This is my country and I’m not leaving,” he said. “A few of us are holding the fort. But when we go, what will happen? There is no one.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.