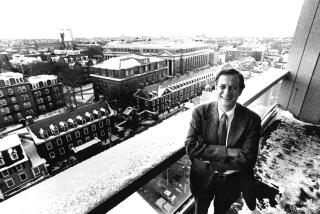

Daniel J. Boorstin, 89; Eloquent Historian Won Pulitzer Prize

Daniel Joseph Boorstin, the Pulitzer Prize-winning and best-selling historian who had served as librarian of Congress and director of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of History and Technology, has died. He was 89.

Boorstin died Saturday of pneumonia at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C.

He wrote two dozen books, which were translated into at least 30 languages and have sold millions of copies around the world.

His best-known works are a trilogy on American history, a trilogy on world history and a 1962 social and cultural commentary titled “The Image.” In that book, Boorstin coined the phrase “pseudo event,” which he described as a staged happening with little or no purpose other than to generate publicity. He also postulated that some celebrities were famous chiefly for being famous.

Boorstin won the 1974 Pulitzer Prize for his 1973 book “The Democratic Experience,” the third volume of his trilogy “The Americans.” The first volume, “The Colonial Experience,” won the Bancroft Award in 1959, and the second, “The National Experience,” won the Francis Parkman Prize in 1966.

“I’m an amateur historian,” Boorstin once said of himself. “One of the advantages of being an amateur is that you don’t get trained in the ruts, so it doesn’t take any originality to stay out of them. I write about what interests me, like packaging, for instance, or broadcasting.”

In the course of a writing career that spanned more than 50 years, Boorstin also wrote about subjects ranging from the evolution of clocks to the first use of elevators and the impact of mail order catalogs. He once described books as humanity’s “single greatest technical advance.”

Good history, he said, also should be good literature. He was known for an ability to synthesize, and for writing with an eloquence that many professional historians lack about how different strands of history came together.

Although Boorstin taught at the University of Chicago for 25 years, he never identified with academic historians. He had been criticized for oversimplification and for overlooking complicated moments of American history, from McCarthyism to Vietnam, and complicated moments of American scholarship, from multiculturalism to feminist studies.

Boorstin was born in Atlanta and grew up in Tulsa, Okla. He entered Harvard University at age 15, and wrote his senior honors thesis on Edward Gibbon’s “The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire.” Gibbon became a role model.

After attending Oxford University’s Balliol College as a Rhodes scholar, Boorstin earned a doctorate in law at Yale. He was teaching at Harvard Law School in 1940 when he met his future wife, Ruth Frankel, who became one of his primary editors over the course of his career.

“Without her, I think my works would have been twice as long and half as readable,” Boorstin was quoted as saying in an introduction to a 1995 Daniel J. Boorstin Reader.

“He was a joy to edit, and he welcomed it,” Ruth Boorstin said. “He welcomed suggestions, and he followed them.”

For a period in the 1930s, Boorstin was a member of the Communist Party. That was an act of youthful folly, he told members of the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1953, and he gave them the names of fellow party members.

In 1969, Boorstin came to Washington from Chicago as director of the Smithsonian’s Museum of History and Technology.

He became librarian of Congress in 1975, over the opposition of the Congressional Black Caucus, which opposed his stands against affirmative action and his attacks on student radicals during the 1960s. As librarian, he directed a $200-million-a-year operation and a staff of 5,800 in three buildings that held 20 million books, and millions more maps, motion pictures, photographs, prints, recordings, videocassettes, presidential papers and such treasures as rare manuscripts and a Stradivarius violin.

He wanted to make the library a “serious but not solemn place,” and he ordered the installation of picnic tables around a plaza and instituted midday concerts. Over some objections, he ordered the bronze doors of the Jefferson Building opened, declaring, “They said it would make a draft, and I say that’s just what we needed.”

In 1987, he retired from the library. “Always leave before they ask you to,” he told a nephew, Robert Boorstin.

During his years at the library, Boorstin habitually rose at 4:30 or 5 a.m., went downstairs to his study and wrote on a manual typewriter for two or three hours before breakfast, then went off to work. He continued to write in retirement, including the book “The Seekers,” which was published in 1998. That was the third volume in his world history trilogy, the other two being “The Creators,” in 1992, and “The Discoverers,” in 1983.

In addition to his wife, survivors include three sons, Paul and Jonathan, both of Los Angeles, and David, of New York; and six grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.