Into every struggle, a little creme anglaise must fall

- Share via

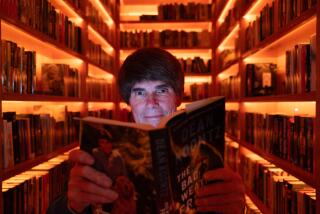

Life Expectancy

A Novel

Dean Koontz

Bantam: 402 pp., $27

*

Dean KOONTZ is so popular, and commands such large tracts of real estate in the nation’s bookstores, that he could probably score a high spot on the bestseller list simply by reworking any of his previous 43 books.

What a pleasure it is to report that in “Life Expectancy,” Koontz takes risks. The book is not simply great fun; it dares to address a serious question: In an age of color-coded terror alerts, how are we supposed to live normal lives?

The story begins on a dark and stormy night. Jimmy Tock is born in the same hospital where his grandfather lies dying. Before expiring, at the precise moment of Jimmy’s birth, Grandpa predicts that Baby Tock will experience five horrific days over the course of his lifetime.

The old man’s prophecy is both specific and vague; he cannot give details as to why these days will be bad, but he does provide specific dates as to when the bad ones will occur.

If only Homeland Security could do that.

Suffice to say that, as shaggy dog stories go, this is the shaggiest; an evil clown is involved, as are such hack devices as rare birth defects and villains who monologue before they murder.

A lesser writer could never pull it off; he’d be tripped up by the logic questions. For example, why doesn’t Jimmy simply sleep off each terrible day, drunk and happy in bed, rather than expose himself to danger in the outside world?

Koontz’s great gift is to maintain suspense even in the face of our incredulity. We worry that Jimmy will be killed even as we know he must survive at least the first four days of tribulation since, after all, a fifth day has been prophesied.

Koontz manages this through a blindingly fast-paced narrative that has enough twists to keep the reader from thinking too deeply about the improbabilities, and by making the reader care so deeply about the characters.

In Jimmy, Koontz has created a perfect Everyman, a nonpolitical regular guy cursed to live in interesting times. Unapologetically unheroic, Jimmy is overweight, slightly offish, a baker by trade; cursed with the knowledge that he has five appointed dates with terror, he follows the admonition to “eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we may die.” But he does so as a modern American would, in moderation, aware of what it means to his diet. Rather than curse fate, he seeks love. And when love appears, in the form of his wife-to-be, it does so as a metaphor for dessert: “She was prettier than a souffle au chocolat drizzled with creme anglaise flavored by apricots, served in a Limoges cup plate on a silver charger, by candlelight.”

Jimmy’s devotion to his family and his desire to survive the five horrible days are both commonplace and heroic. His life’s dream is to be left alone. Yet evil intrudes like clockwork. And still his dream endures.

“No one’s life should be rooted in fear. We are born for wonder, for joy, for hope, for love, to marvel at the mystery of existence, to be ravished by the beauty of the world, to seek truth and meaning, to acquire wisdom, and by our treatment of others to brighten the corner where we are.”

The hardest challenges Jimmy faces are not the five cataclysmic days but the problems that occur between them: the sickness of Jimmy’s children, the stresses of Jimmy’s marriage, Jimmy’s acceptance of mortality and life’s limitations. Koontz reminds us that merely surviving the day-to-day struggles is a challenge and a blessing not to be taken for granted. There may be trouble ahead, Koontz tells us; indeed, it is all but guaranteed, so let’s face the music and dance. Or at least eat dessert. Perhaps suspense novels don’t need a moral, but bless Koontz for giving us one anyway: “No one can grant you happiness. Happiness is a choice we all have the power to make. There is always cake.”

*

Jonathan Shapiro was a writer and producer for the television drama “The Practice.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.