Compelling style over substance

Novelist Colson Whitehead’s latest, “The Colossus of New York,” isn’t a work of fiction, but it reads like a collection of stories in which his native city is both plot and protagonist. In short essays such as “Central Park,” “Downtown” and “Times Square,” the author riffs and ruminates on the place and its people.

In his two novels, “The Intuitionist” and “John Henry Days,” Whitehead displayed grand ambition. Here he is a miniaturist, offering 13 brief pieces that read more like sketches or journal entries than fully developed essays. Though the author has opted for style over substance, his prose is compelling, partly because his awe for the city is so apparent.

The book opens with a confession, or at least an explanation: “I’m here because I was born here and thus ruined for anywhere else.” As Whitehead examines the complexity of New York, he dissects as well what it means to be a New Yorker. “No matter how long you have been here, you are a New Yorker the first time you say, That used to be Munsey’s, or That used to be the Tic Toc Lounge.... You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is there now.”

To Whitehead, the definition of New York is always private, ephemeral, uncontainable. “There are eight million naked cities in this naked city,” he writes. “The New York City you live in is not my New York City; how could it be? This place multiplies when you’re not looking.” In his more successful pieces, Whitehead shows the extent to which our identities are linked to our sense of place; the layers of memories we hold of a city are links to our past selves -- personas, relationships, jobs, apartments. “Our cities are calendars containing who we were and who we will be next,” he writes.

Too many passages in the book are hazy or flat, however. This collection reads as though nearly every observation, no matter how banal, was included. In “Port Authority,” a piece about traveling by bus, Whitehead notes, “Something happens to the bags up there in the baggage racks. When you go to get something out of them they are inexplicably heavier, as if they repacked themselves when you weren’t looking.” And: “Thank God for the white detachable headrest slipcovers, an invention that saves us from germs. Pat pending.”

Throughout the book, there is a sameness to Whitehead’s sentences, a staccato, pseudo-jazzy rhythm that becomes trying after a while: “Once a year he takes the walk. There can be no destination. No map. Live here long enough and you have a compass.” Writing on the Brooklyn Bridge: “What did you hope to achieve by this little adventure? Nothing has changed. Nothing ever changes. Presentiment of doom. Closer you get to the other side, the slower you walk. On the other side there is no more dreaming. Just solid ground. So put it off for as long as possible.”

In certain passages, the choppy sentences and multiple perspectives perfectly serve the scene being depicted -- most effectively in “Times Square.” Whitehead captures the speed with which the city’s goings-on zoom by and the barrage of images its citizens are subjected to every day, night, hour, minute. But in the end there are too many fragments of this New York portrait to stitch together, and little of it is memorable.

“The Colossus of New York” is elusive, like the city itself. Whitehead describes the grandeur of New York, along with its most quotidian and irritating aspects. But it’s hard to imagine anyone who isn’t a current or former New Yorker caring about any of this. Purely in terms of technique, Whitehead knows how to dazzle, but we knew that already. His previous fiction had a depth and intricacy this collection unfortunately lacks.

If this were a first book, it could be seen as an impressive accomplishment. Since Whitehead has established himself as a heavy hitter, though, expectations are justifiably higher. To be fair, Whitehead not at his best is more engaging than some writers at their very best.

Abstractness or lyricism is certainly welcome in nonfiction, but a little more directness would have served this book well. Various great insights appear in flashes; taken no further, they prove disappointing.

“The Colossus of New York” reads like pages from the notebook of a highly imaginative, exceedingly gifted writer. You hope he’ll win you over again the next time around.

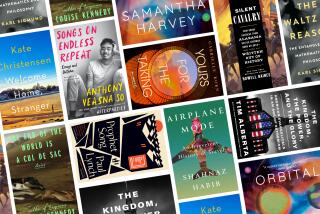

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.