The beat goes on

Having been fortunate enough to work with some of the best drummers in the world, I can honestly say that anyone using a machine in preference to the real thing is usually doing so for economic reasons rather than artistic.

Drums are one of the most challenging instruments to capture on tape, and for this reason it’s more cost effective to use a machine, although I doubt anyone would argue that they’d prefer a mechanical device to the feel and interpretation of their drummer of choice.

The days of the individual making big session bucks are being replaced by a musical community where musicians exchange services and contribute to each others’ projects in lieu of financial reimbursement. The payback comes much later, but a broader network of musicians helping and supporting each other is a fair trade-off for Rolls-Royces and “houses on the hill” for a select few.

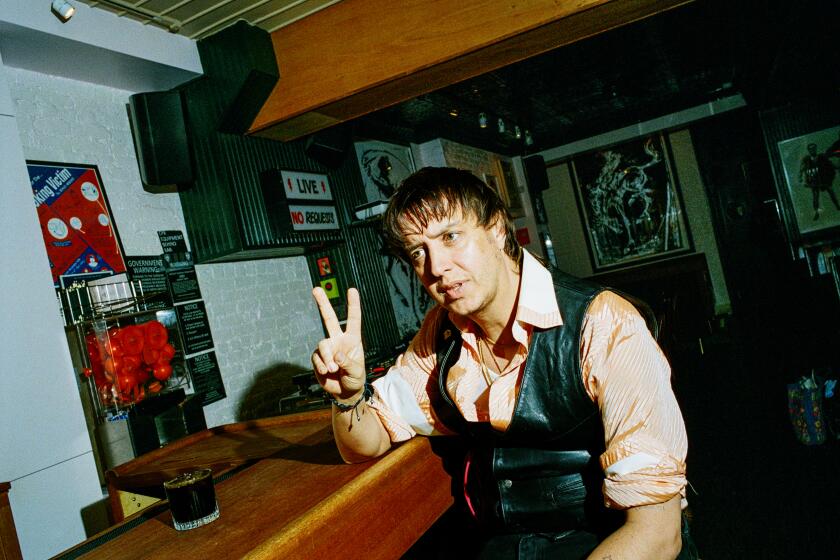

Brett Garsed

Thousand Oaks

*

“Beat at Their Own Game” omitted one very important session drummer: Earl Palmer.

The New Orleans legend not only played on most of the hit records by Fats Domino, Little Richard, Professor Longhair, etc., in the early to mid-’50s, but then came out to Los Angeles in the late ‘50s, where he played behind Ricky Nelson and many others. When his workload became too much, he passed many of his studio gigs to the “new guy,” Hal Blaine. Jim Keltner and Hal Blaine would agree that Earl is the godfather of studio drummers.

Robert Leslie Dean

Los Angeles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.