More May Not Be Better, Medicare Study Says

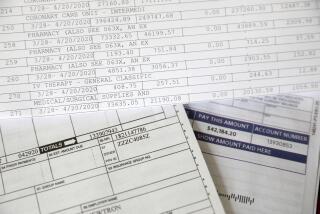

In Los Angeles and other areas where Medicare spending was among the highest in the nation in the mid-1990s, elderly patients neither lived longer nor experienced a better quality of life than where spending was lowest, according to a comprehensive study to be published today.

Medicare patients being treated for serious, often life-shortening conditions in the highest-spending regions got about 60% more care but “we don’t see any evidence they’re living longer,” said Dr. Elliott S. Fisher, lead researcher for the study, to be published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Nor did Medicare patients in the lower spending groups deteriorate faster. “There’s no difference in the rate of decline,” said Fisher, an internist, Dartmouth Medical School professor and co-director of the Outcome Group at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in White River Junction, Vt.

By these and other measures, including access to care and patient satisfaction, the study determined that people receiving the most care did not fare better.

In a country with 40.3 million Medicare beneficiaries and rapidly rising health-care costs, the implications are substantial for the government insurance program serving elderly and disabled people, researchers said. According to the latest figures available, Medicare spending increased 7.8% in 2001 over the previous year.

With more restraint on the part of physicians, the study concluded, “savings of up to 30% of Medicare spending might be possible, and the Medicare Trust Fund would remain solvent into the indefinite future.”

But the researchers, who looked at nearly 1 million patients in 306 cities and counties nationally, warned that those seeking to cut costs in the higher-spending regions should proceed with caution and await further research.

In an accompanying commentary, former Medicare administrator Gail Wilensky said the study offered “the best rationale to date ... to drive down spending in high-expenditure areas of the United States.”

Wilensky noted, however, that figuring out how to set limits is difficult: “We need more thought about how to reward physicians who practice high-quality conservative medicine.”

To set up the study, the researchers -- most of whom are from Dartmouth -- established Medicare spending patterns across the country, based on what was spent, on average, in the last six months of life.

They chose end-of-life spending to ensure the similarity in the various regions of the health status of the patients involved. The study also was adjusted for sex and race of patients and geographic variations in Medicare pricing.

Los Angeles ranked third among U.S. areas, spending an average of $15,479 per person in the last six months of life from 1994 to 1996. Miami was the highest-spending area, with an average of $17,564 per patient, and Manhattan ranked second with $16,333.

Once the researchers knew the levels of spending throughout the country, they identified patients in various spending areas who were suffering from one of three serious conditions -- heart attacks, hip fractures or colon cancer.

The study identified the patients upon first hospitalization and followed them for as long as five years, until the end of 1997. A little more than half of those patients lived.

Researchers also looked at another group -- a representative sampling of about 18,000 Medicare patients.

They found that having greater resources in a region -- such as more hospital beds and specialists -- did not mean patients experienced “improved access to care, better-quality care, or ... better health outcomes or satisfaction,” according to the study.

Oddly, Medicare enrollees in higher-spending areas were slightly less likely to get certain recommended follow-up care, the study found.

For instance, patients who had suffered heart attacks in the higher-spending regions were less likely to receive exercise testing and less likely to have received aspirin in the hospital and upon discharge -- a standard recommendation for heart attack patients.

Fisher speculates that may be because of confusion resulting from being treated by multiple specialists. “If there are five specialists involved in your care, each one is going to be slightly less likely to take responsibility for your care” -- and more likely to think “another doctor has prescribed aspirin.”

The study took years because of the time needed to collect claims data, analyze it and subject it to critical review.

“One of the things I hope comes out of our study is a willingness to question whether a more intensive practice or intervention is in our interests,” Fisher said.

“We Americans assume more medical care means better medical care,” Fisher said.

Generally, the higher-spending areas had more teaching hospitals, more beds, more physicians and a higher proportion of urban residents.

Patients in the highest-spending group got more tests and more physician visits and stayed in the hospital longer and more often.

They were more likely to see specialists than patients in the lowest-spending group, where people were more likely to see family practitioners. And they were likely to be treated more intensively if and when they became gravely ill.

“It appears likely that physicians in all regions are simply managing their patients with available resources and that in-patient management and subspecialist consultation are easier in regions where these resources are readily available,” the researchers wrote.

“Some of it is capacity and some of it is the medical culture,” Fisher said in a telephone interview.

“We’re doing further study on the causes and consequences of the variations, Fisher” said.

Bend, Ore, the area that spent the least on Medicare patients -- $7,238, on average -- stands out because of its well-established hospice movement, which ministers to the terminally ill and their families.

Hospices help patients manage their illnesses and their pain, instead of seeking aggressive treatment.

The city of Bend, with a population of 52,000, has only one hospital (another reason it might rank among the lowest Medicare spenders).

“It helps that we have a good relationship with the physician community and the hospital,” said Sharon Strohecker, executive director of 23-year-old Hospice of Bend-LaPine. “You have to do a lot of training ... to get them on board,” to get them to ask patients: “ ‘Have you thought of hospice?’ ”

Within California, San Luis Obispo ranked the lowest in Medicare expenditures on dying patients, spending an average of $8,474.

The researchers were careful to say that their findings should not be used to justify wholesale changes in care.

“We can’t say that changes would be safe,” Fisher said. “It all depends on how change is implemented. To take an extreme example, consider forcing 30% of the docs in L.A. to move to an area that needed more. This would clearly result in disruptions in current relationships and care patterns that might -- at least in the short term -- be harmful.”

Moreover, doctors treating the elderly point out that they are treating individuals, not statistics.

Thomas Lagrelius, a geriatrician who heads the family medicine department at Torrance Memorial Medical Center, said he is not thinking about public health studies and spending when he walks into an exam room.

“My job is not to save Medicare money,” he said. “My job is to walk into one room and see one patient and do the best I can for that one person. I incorporate a million pieces of information into that discussion. If I allow that expertise to be influenced by a public health attitude, I am not doing my job as a fiduciary for that patient.”