Vaccine versus MS

- Share via

In the early phase of multiple sclerosis, symptoms are often intermittent and patients are able to lead relatively normal lives. But the problems can worsen over the years, causing speech difficulties and cognitive impairments -- and leaving some people dependent on wheelchairs.

If it proves successful, a vaccine still in the early stages of testing could halt the progression of this chronic disease.

“We’re hopeful the vaccine will prevent irreversible nervous system degeneration and disability,” says Dr. Norman J. Kachuck, a neurologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine who has studied the vaccine. “It could make a profound difference in how these patients are treated.”

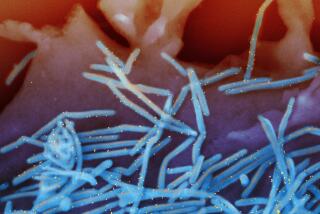

Multiple sclerosis is believed to be an autoimmune disease in which immune system cells, known as T-cells, begin to destroy the fatty substance that coats and insulates nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord. The breakdown of this substance, called myelin, disrupts the transmission of electrical signals from the brain, causing such symptoms as fatigue, muscle weakness, heat sensitivity, loss of balance, difficulty walking and slurred speech.

In the early phase of the more common form of this condition, known as relapsing and remitting MS, symptoms occur only periodically. Each episode causes more scarring of the myelin, however, so that for about half of these sufferers, symptoms worsen over the years.

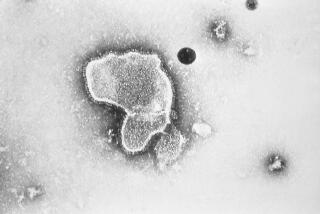

People whose multiple sclerosis has evolved into the more progressive form of the disease are treated with beta interferon and mitoxantrone, which suppress the immune system and can reduce the severity and frequency of attacks. However, beta interferon (which fails to help more than three-quarters of patients) can cause flu-like symptoms and fatigue, and mitoxantrone can damage the heart. These drugs also can deplete the immune system.

“We now realize that the immune system needs to be intact in order for the nervous system to be protected and to repair itself,” says Kachuck, the co-principal investigator in the vaccine’s clinical trials.

The USC-invented vaccine is a more precisely targeted therapy, prompting the body to destroy just the renegade immune system cells without harming the rest of the immune system. First, researchers remove immune cells from individual patients, then isolate the T-cells programmed to attack the myelin. The cells are then exposed to radiation, which kills them. Consequently, when the resultant vaccine, called T Cell Vaccine for MS, is introduced into the body, the immune system sees it as foreign and dispatches “good” T-cells to destroy the MS-causing “bad” T-cells.

“We’re giving patients the capacity to mount their own immune response, which could prevent further damage,” says Dr. Leslie P. Weiner, a neurologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine and a vaccine co-inventor.

A 1997 test of this strategy on four severely afflicted MS patients was encouraging. “They showed a dramatic anti-myelin response, and in one patient, the disease stabilized for more than five years,” says Weiner.

Three years ago, researchers began a larger trial of the customized vaccine, which encompassed 84 patients. Half got a series of injections of the active vaccine over a two-year period, while the others received placebo shots. Test results should be available some time in 2005.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

In search of a new test

Patients who have an initial episode of what appears to be multiple sclerosis can’t be diagnosed with the disease until a second event, which may occur years later -- after the nervous system already has been damaged.

Early treatment with interferon might slow the progress of the condition. But because the drug has significant side effects and costs about $14,000 a year, patients are reluctant to undergo treatment unless they have a definitive diagnosis.

A potential blood test may help identify MS patients early on. Austrian researchers reported this summer that the presence of two specific antibodies could predict which patients will go on to develop MS. In a study of 103 patients who had an initial MS-like event, nine of 39 patients without the antibodies had another episode. In contrast, 21 of 22 patients with both antibodies relapsed.

Such a test would “provide a little extra impetus for people to get early treatment,” says Dr. Norman J. Kachuck, a neurologist at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.