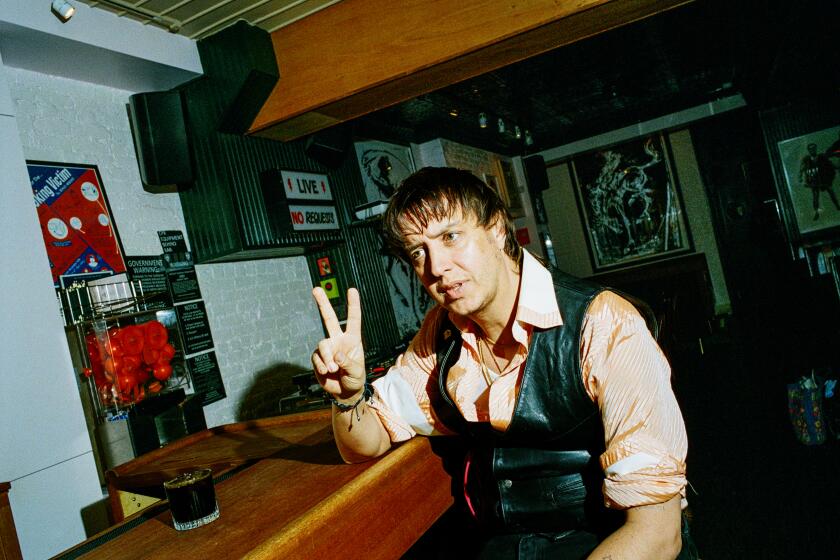

Their ‘Son’ was Fogerty’s baby

Put yourself in John Fogerty’s shoes and see if you don’t feel like slapping somebody.

Fogerty, the guiding force behind Creedence Clearwater Revival’s hits of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s and now a solo performer, has fretted for more than two years as one of his most meaningful songs, the Vietnam War-era protest anthem “Fortunate Son,” has been used by Wrangler as a patriotic endorsement of its jeans.

“It makes me angry,” he said by phone from his home in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife and four children and is writing songs for a new album, his first since 1997. “When you use a song for a TV commercial, it trivializes the meaning of the song. It almost turns it into nothing.”

Wrangler was able to have its way with Fogerty’s 1969 hit because he long ago signed away legal control of his old recordings to Creedence’s record label, Berkeley-based Fantasy Records. Without consulting Fogerty, Fantasy sold Wrangler permission to use the lyrics and master recording of “Fortunate Son,” a stark, hard-rocking song about privilege and hypocrisy.

Wrangler estimates the commercial has so far received 3 billion “impressions,” or individual viewings. The company boosted its TV buys 25% this year to promote its Five-Star Premium Denim line, which means a significantly higher number of people are noticing the use of the song.

“People walk up to me, people I’ve met through my kids, at school, people who rarely talk to me about the old days, and they say, ‘Oh, John, I saw your commercial,’ and the first thing out of my mouth is: ‘It stinks,’ ” said Fogerty, who first saw the spot in the summer of 2000. “They usually get a surprised look on their face -- they’re just making conversation -- and then I have to explain.”

What hurts the most, he said, is the reaction he fears from men who were of draft age during the Vietnam War, men for whom “Fortunate Son” protested the unfairness of the loophole-filled Selective Service System. “It really ticks me off that they’re thinking, ‘Oh, they got to John. Musta given him a new boat or something.’ ”

Fogerty’s angst stands out in a pop-music climate where the notion of “selling out” seems to have disappeared decades ago. Old rock hits are routinely used in TV commercials to sell everything from cars to detergent to cell phones to toothpaste. Younger bands welcome -- and sometimes solicit -- the exposure commercials bring. Two years ago Moby became the gold standard for this ethos by licensing all 18 songs on his album “Play” to commercials or movies.

Wrangler and its ad agency created a 30-second commercial that exploited Fogerty’s song’s explosive guitar-and-drum instrumental opening. As jeans-clad actors frolic, the first two lines of the song can be heard :

Some folks are born made to wave the flag

Ooh, they’re red white and blue

In the context of the ad, the lines are an appeal to your sense of Americanism, just what a company would want you to associate with its product. There’s only one problem: That opening couplet alone does not convey the theme of the song, in which Fogerty shrieked about the way he felt those phony patriots were sending everyday men to their deaths in an endless quagmire:

Some folks inherit star-spangled eyes

Ooh, they send you down to war

And when you ask them how much should we give?

They only answer, “More, more, more”

With each chorus he proclaimed:

It ain’t me, it ain’t me, I ain’t no fortunate one

Craig Errington, director of advertising for Wrangler’s parent corporation, North Carolina-based VF Jeanswear, said the company was initially drawn to “the energetic, uplifting sound and beat ... that makes you turn your head back to the TV.” He said the company studied the lyrics and concluded that “Fortunate Son” was not merely an anti-war song but “more an ode to the common man.... The common man is who we have been directing Wrangler toward.”

Fantasy’s director of musical licensing, Pamela Bendich, said Fantasy had “a very clear concept of what the commercial was.... I didn’t find it misleading.” Neither she nor Errington would discuss how much Wrangler paid to use the song.

Fogerty is financially compensated by Wrangler as the song’s author (as he was by a paint company a decade ago when, to his dismay, it used Creedence’s “Who’ll Stop the Rain”) but says he finds that hollow. At age 57, he still holds unabashed ‘60s political views, and to him the Wrangler commercial is a crime against his generation.

“I happened to be on tour in a hotel room somewhere in America the first time I heard the Beatles’ ‘Revolution’ used in a Nike commercial” in 1987, the result of the group’s having lost the rights to the song.

“The trash can they provide in my room clanged against a wall. That was my reaction to that then -- they’re stealing something from me.... All my emotions welled up then at another nail in the coffin of the ideals of the ‘60s.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.