His Image Was Key to the City

Now that the NBA logo has picked up and moved to Memphis--what next, Chick Hearn to the Toronto Raptors?--it’s time to finally say something about that logo that should have been said long ago.

It’s all wrong.

The famous silhouette of Jerry West, yo-yoing right to left to right across your dial, driving effortlessly toward a silken 20-foot pull-up jumper, is quite literally only a shadow of the real thing. Essential details are missing.

Where is the ragged-ridge nose that was busted more times than the Celtics broke his heart?

What about the heavily wrapped hamstring he used to drag down the court on the way to another 40?

Or the perpetual look of torment crossed with determination, as if West deep down realized that no matter what he did or how mightily he tried, the outcome was out of his hands--and, chances were, it wasn’t going to be a happy one.

That indelible image of West--hobbled by injury and his supporting cast and Bill Russell in the other uniform, yet refusing to relent until the final buzzer temporarily suspended the misery--embodied the Los Angeles sports fan experience of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s. Long before winnin’ time, there was wincing time. You could set your calendars to it: West would carry the Lakers to another NBA Finals, West’s body would try to systematically shut down on him, he would grimace through the pain and average 31 points and eight assists, and the Lakers would lose in seven.

West was Sisyphus in sweat bands, forever pushing the basketball up an unconquerable mountain.

Deep down, we too had a pretty good feeling of how it was all going to end, but like West, we flinched along for the ride every spring. And there was nobody we’d rather have pushing that ball.

West tilted many of his windmills at a time when the Rams raised and crushed expectations every December, the Dodgers tumbled into post-Koufax malaise and the Angels were a good way to buy field box tickets 10 minutes before the first pitch. These were not easy days to grow up in Los Angeles rooting for the home team.

It would have been much simpler, and smarter, and healthier, to tear the pennants off the wall and throw away the sports section and swear to come out of hibernation only for UCLA basketball season.

Why did we keep coming back, half-knowing that nothing good was ever going to come of it? Because of West.

Every last-second jumper West nailed--and there were scads of them, more than Michael Jordan could ever imagine--created another sliver of hope. If the doctors said West could go, taped up and and stitched up and propped up, the Lakers had a chance, Los Angeles had a shot.

The most famous basket of West’s career, the 63-footer at the end of Game 3 of the 1970 Finals, said really all that needed to be said. Lakers losing again, down by two with a couple of seconds to go. They inbounded the ball and the dejection in Hearn’s voice echoed the disappointment of thousands of Laker fans slumped over their radios.

“West throws up an 80-footer,” Hearn said, primarily for the record, and if he was a few feet off on the guesstimate, who cared, everyone knew the Lakers were done for.

Hearn paused, long enough to allow the stomach-churning dread to begin to dissolve into resignation.

“GOOOOOODDD!!!!”

What?!?

Incredibly, West had tied it at the buzzer. In typical West-era Laker fashion, the shot occurred nine years before the NBA adopted the three-point rule--although Laker center Wilt Chamberlain, ever a progressive thinker, jogged into the locker room, thinking the game was over.

Then, in typical West-era Laker fashion, the teams returned to the court and the Lakers lost in overtime, on their way to another seven-game defeat, this time to the New York Knicks.

Two years later, the Lakers finally broke through and West won his first and only NBA title as a player. Occasionally, ESPN Classic will show footage of the final seconds of the clincher and the immediate aftermath. While pandemonium erupts around him, West looks totally spent, as if the long previous decade of near-misses had drained away the will and the energy to even muster a smile.

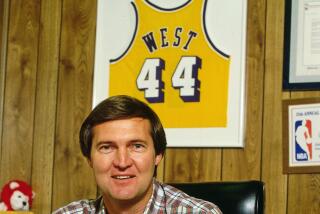

Later on, during his years as Laker coach and general manager, we discovered this was merely the everyday Jerry West work mode. He never relaxed, he was never satisfied, even as he assembled the Showtime Lakers of the 1980s and reloaded in 1996 with quite possibly the greatest summer an NBA executive ever manufactured--signing free agent Shaquille O’Neal, trading for the rights to Kobe Bryant and drafting Derek Fisher.

Younger fans, weaned on Magic Johnson’s ever-ready grin amid confetti showers, couldn’t relate. Why won’t the guy ever loosen up? Why can’t he just enjoy the windfall?

Here’s why: When everyone else saw Shaq dunking over David Robinson, West saw Russell pointing to the Forum rafters and waving another No. 1 finger in the face of the Lakers. When everyone else watched Kobe blowing by Allen Iverson, West couldn’t escape the image of Don Nelson sinking the Lakers in yet another Game 7.

Even with the Grizzlies, where history and expectation are currently deadlocked at zero, those are the ghosts that will continue to eat at West, to drive him, even with his legacy still glittering on the walls and the hardwood inside Staples Center.

Now that the Lakers have decided to acknowledge their Minneapolis heritage, fans can easily count the banners and do the math: 13 league championships, with No. 14 potentially looming in June.

From there, the climb gets very interesting. Two more titles by the team West built and left behind and the Lakers would equal Boston’s all-time record of 16.

Maybe then, but only then, West would have a legacy he could live with.

As good as the Celtics. At last.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.