Saving Capitalism From Itself

- Share via

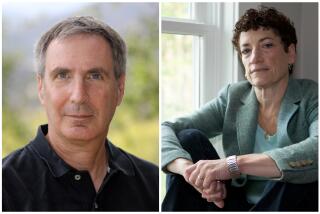

At first blush, John Maynard Keynes might seem an unusual choice as one of the last century’s most influential people, and “Fighting for Britain, 1937-1946,” the third thick volume by Robert Skidelsky of the British economist’s life, might seem a tough sell, especially to an American audience.

After all, Keynes was a terrible snob, particularly when it came to the United States (“I always regard a visit as in the nature of a serious illness”). Early in life, he flouted enough social conventions to make the average 1960s hippie look like an Eagle Scout. (He had a series of lovers, male and female. Even once he had become a government official, he dashed off a book calling the prime minister, David Lloyd George, a “goat-footed bard” and “half-human.”) He was a mama’s boy; he wrote his mother regularly and dined with his parents most weekends until his death at 63.

But Keynes also pulled off one of the great intellectual coups of the century, an accomplishment as original in its way as Adam Smith’s initial discovery of the inner logic of a market society. He figured out how to look at an economy from the top down, just as Smith had figured out how to view it from eye level out.

And the former aesthete and rebel did something else as well; he demonstrated the power of his top-down approach in a series of policy proposals that, although not immediately embraced by the British and American leaders on whom he pressed them, turned out to be what each society needed at the time. Keynes’ encounter with Franklin D. Roosevelt in the midst of the Great Depression, described in Skidelsky’s second volume on Keynes, offered a glimpse of the advice and its initial reception. The economist gained an audience with the president at which he lobbied for budget deficits on a scale unthinkable at the time to pump up consumer demand and revive growth.

“He left a whole rigmarole of figures,” a peeved Roosevelt complained. Keynes was no kinder, remarking that he had “supposed the president was more literate, economically speaking.” But when FDR finally managed to run the kind of deficits Keynes had recommended, with the American entry into World War II, the policy worked like a charm. United States output nearly doubled; unemployment fell through the floor.

Getting it right on such a grand scale helps explain why Keynes is considered so influential. But it doesn’t answer why a reader should wade into “Fighting for Britain, 1937-1946.” The book covers the last nine years of Keynes’ life when, in a role that amounted to being Churchill’s Treasury secretary, the economist orchestrated the financing of Britain’s war against Germany and sought--in large part unsuccessfully--to craft a postwar economic order that left Britain with some of its prewar empire and a degree of freedom from the United States.

Skidelsky’s previous two volumes on Keynes’ life, “Hopes Betrayed, 1883-1920” and “The Economist as Savior, 1920-1937,” cover Keynes’ early years through his involvement as a young treasury official in the Versailles Peace Conference (which settled World War I on terms that he predicted would produce another conflagration) and on to the writing of his masterwork, “The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money.”

Beyond rounding out one’s picture of Keynes, there are at least three reasons why an American reader in particular would tackle this volume. All have to do with the parallels between the period leading up to World War II and the extraordinary political moment at which the United States now finds itself.

Then, as now, the world appeared to be moving from peace, or at least limited conflict, to generalized global struggle. Keynes was faster than almost any of his contemporaries in realizing that the coming of war would utterly change the British economy, requiring policymakers to drop concern about depression in favor of worries about rising demand, inflation and shortage. Whatever the differences between this era and that, Keynes’ efforts to gauge the economic dimensions of the shift from peace to war provide a useful counterpoint to the untenable picture now being painted by President Bush of a nation at war with its economy at peace.

Just as important, Americans saw themselves as innocents drawn into a conflict they would sooner have avoided and fighting only for such grander goods as defeating evil. Virtually all American histories of the period leading up to World War II are written from this perspective. But not all British histories.

To many British, and especially to Keynes, the terms of United States war loans to England as well as American postwar economic plans were clearly designed to weaken the United Kingdom and leave it servile. “America must not be allowed to pick out the eyes of the British Empire,” he fumed as the full dimensions of the economic damage to his homeland became clear. In laying out such a drastically different account of United States aims in a past war, the book provides an important counterweight to the wildest claims of purity and innocence advanced by the United States in the current conflict.

Finally, both now and then, there is a new urgency to reconciling what the recently deceased Harvard philosopher Robert Nozick described as the right of consenting adults to engage in capitalist acts with society’s broader needs for order, security and allegiance. For nearly two decades, Americans have assumed that the answer lay in private growth. But with the Enron scandal leaving people bereft of retirement savings and the terrorist attacks revealing the weak links in the private provision of public goods such as airport security, the answer looks more like a dodge.

Keynes faced the problem under very different circumstances. War production was beginning to fill the pockets of once jobless workers with cash just as British factories, occupied with munitions, were unable to produce for them. There seemed to be only two options for what to do: Nothing, which would have resulted in inflation, bare shelves and perhaps social chaos, or rationing, which Keynes argued would push Britain in the direction of the very totalitarian regimes it was then battling.

Keynes came up with an alternative: forced savings. “It is for the state to say how much a man is entitled to spend out of his earnings,” the economist declared. “It is for him to say how he will spend it.”

The idea was direct, forceful and still respectful of individuals’ right to lead their own lives. That Keynes could devise it on the fly and in the midst of frantic war preparations offers some hope that Americans, in a wealthier and calmer time, might find solutions to their economic problems that meet the same exacting standards.

Much of this final volume is haunted by failure. Keynes failed to sell his notion of forced savings. He failed to save Britain from American domination. He failed to even survive negotiations over the postwar order, which left him spent and vulnerable to a chronic heart condition. But the subsequently announced death of his ideas has proven spectacularly premature. As Skidelsky’s biography demonstrates, that is because--beyond the specifics of theory--Keynes engaged in a life-long search for a middle way between the excesses of capitalist competition and the brutalities of totalitarian order, one that represents the very best liberalism has to offer.