Avoiding Doctors: A Guy Thing

- Share via

What was Darryl Kile thinking the night before he died? It was widely reported that the St. Louis Cardinals pitcher had complained to his brother of shoulder pain and weakness the evening before he was found dead in his Chicago hotel room June 22, at age 33.

Maybe Kile believed that the soreness and fatigue came from overexerting himself on the diamond, and so he didn’t recognize classic warning signs of the severely clogged arteries that a coroner later concluded were the likely cause of death. But Kile’s father had died at 44 of a heart attack and stroke in 1993, and one couldn’t help but wonder why the pitcher hadn’t sought medical attention that evening.

We’ll never know, and second-guessing won’t bring back the admired athlete, husband and father. But Kile’s death does raise anew a question that has long frustrated physicians: Why are men so reluctant to seek medical help?

Doctors have long known that many guys would rather clean gutters or watch synchronized swimming than schedule an office visit. For example, in March, the science journal Neurology reported that more than half of all male migraine sufferers never consult a physician about their pain, compared with only about a quarter of female migraine sufferers who don’t see a doctor. A poll in 2000 by the Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based philanthropy and research group, found that American men are three times more likely than women to go a year without seeing a doctor. And one in four males would wait “as long as possible” before having a health concern checked out by a physician, the poll found.

In one sense, these statistics aren’t difficult to understand. Cavemen, presumably, didn’t sit around whining if chomped by a saber-toothed tiger. They had to tough it out and protect their clan or risk extinction. Some observers believe that remnants of that mentality persist today.

“It’s inculcated in men that we have to be the breadwinner, have to be strong, can’t acknowledge weakness,” says Harold L. Pass, a psychologist at Stony Brook University Hospital in Stony Brook, N.Y., who specializes in male psychology. “As a result, men tend to minimize medical symptoms when they first appear.”

But waiting only makes a problem harder to treat once the guy decides to get help. Our foot-dragging is often fueled by fear of embarrassment, experts say. What if there’s really nothing wrong with me? I’ll look like a hypochondriac. Or worse--a sissy.

Pass has a friend who developed serious chest pain but waited nearly 10 hours before going to an emergency room because he worried that the throbbing might be nothing more than heartburn. One little detail makes this story of masculine denial truly disturbing: The guy was a doctor. (He did have a mild heart attack, from which he recovered.)

The pressure to conform to masculine stereotypes begins early in life. Many of us were brought up in environments that encouraged silence in the face of aches and maladies. If you skinned your knee and burst out crying, you risked being called a big baby. When the same thing happened to your sister, however, she probably got a hug and a lollipop. Youth sports coaches often sneer at bumps and bruises, imploring youngsters to “walk it off” and get back in the game.

Playing with pain is celebrated as manly and brave. There are these examples from the sports world: Former Los Angeles Dodger Kirk Gibson hobbled off the bench with a bum knee to hit a game-winning home run in the 1988 World Series; Willis Reed, of the New York Knicks, played in the seventh game of the 1970 NBA championship on a broken leg; and Los Angeles Laker Shaquille O’Neal played last season with severe arthritic pain in his right big toe.

What’s more, in most families women run the medicine show, which leaves a lasting impression on little boys, says Ian Banks, a physician in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and president of the European Men’s Health Forum. In November, Banks wrote an editorial in the British Medical Journal explaining why men feel alienated from the health-care system, which he calls “no man’s land.”

“We brainwash our children into accepting that health is a women’s issue,” Banks said in a phone interview. In his own practice, he notes, little boys almost always arrive accompanied by a mom, sister or grandmother, but rarely a dad or other male relative. As kids mature, the perception that health awareness is women’s work only gets stronger. When girls reach puberty, they start seeing gynecologists for annual checkups, which gets them into a routine of visiting a physician at least once a year. But there’s no equivalent specialty for men.

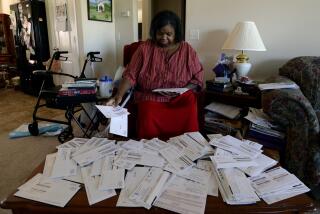

For many men, seeing a doctor when they feel ill simply isn’t an option. In the U.S., three out of five males with annual incomes below $16,000 lack health insurance, while the same is true for about only one-third of women in the same economic background, since many are covered by Medicaid, says David Sandman a health-policy analyst with the New York-based Commonwealth Fund, a philanthropic group. And once men find their way into a doctor’s office, says Banks, many find it difficult to discuss personal problems with other males, who still make up the majority of physicians in the United States. To make matters worse, Banks says, some doctors come out of the dog-eat-dog climate of medical school imbued with a macho mentality, believing--consciously or not--that men don’t complain, that men can cope with pain. The result, Banks wrote in the British Medical Journal, can be a “testosterone-driven consultation.”

No wonder some guys never go back. The medical profession needs to do a better job of reaching out to men and making us feel like we’re part of the system. But, in the end, we have to take greater responsibility for the upkeep of our bodies. Health professionals stress that it’s critical to have a regular physician you can see for annual checkups and when health concerns arise. Make your own appointments and fill your own prescriptions; you’ll feel more in control of your medical care. Finally, take action when that little voice in your head tells you something’s wrong.

He who hesitates is all too often lost.

*

Massachusetts freelance writer Timothy Gower can be reached by e-mail at [email protected]. The Healthy Man runs the second Monday of the month.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.