From Historic Hall to Victim of New Economic Realities

- Share via

SHANGHAI — To see how much China has changed since Richard Nixon flew here 30 years ago and shook hands with the Communists, look no farther than the hotel where the famous Shanghai Communique was inked.

The hotel’s simple two-story assembly hall where history was made has been bulldozed. Instead of saving it as a tribute to the rapprochement, the Chinese tore it down five years ago to make way for a state-of-the-art conference facility, complete with underground parking and an indoor swimming pool.

“Sure we care about what happened here in the past, but we also care about staying competitive,” says Qiu Huanxi, head of the general manager’s office at the Jin Jiang Hotel. “If we didn’t tear down that old building, we wouldn’t be able to make a profit.”

The American side was perhaps more sentimental about the structure. After leaving office in 1974, Nixon paid two nostalgic visits to the old European-style hotel where he had spent a sleepless night finalizing the terms of the communique. By recognizing differences and shared goals, the document laid the foundation for bilateral ties. Its cornerstone was the declaration that there is only one China and Taiwan is part of China.

“Nixon was very happy, and he kept asking for ‘More Maotai! Maotai!’ ” said Jiang Jinbao, now 77, referring to the name of a Chinese liquor. Back then, Jiang was in charge of room service for the 16th floor presidential suite.

President Bush timed his first official state visit to China to coincide with the 30th anniversary of Nixon’s voyage to the Middle Kingdom. The Chinese tend to pay attention to anniversaries, especially the politically symbolic kind. But probably because Bush’s trip is to Beijing, Shanghai is playing it rather low-key.

Most of the hotel staff members from three decades ago have either died or retired. Those few who are still around play down their involvement, perhaps out of habit from a bygone era.

“We were told, ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell. Let whatever you know or don’t know rot in your stomach,’ ” said Qiu, who was a 23-year-old front desk clerk at the time.

Wang Fengxian was a 25-year-old waitress. She served food to Nixon’s table during the banquet. But she was told not to breathe a word of it to her relatives or even jot anything down in her diary.

Those were politically charged times. China was in the midst of the Cultural Revolution. The United States was considered by Chinese as an imperialist evil, and its president was the symbolic public enemy No. 1.

A state newspaper greeted Nixon’s arrival with an editorial stating, “The purpose of shaking hands with the enemy is to better destroy the enemy.”

Decades of mutual animosity had been virtually the only common ground between the two countries. The hotel staff, however, were told to swallow their pride and play the good host. They were ordered to remove popular slogans of Chairman Mao Tse-tung from the hotel rooms and replace them with apolitical Chinese paintings.

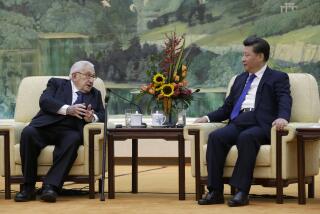

“We never detected any hostility,” said Winston Lord, a former U.S. ambassador to Beijing who was then an aide to Henry A. Kissinger, Nixon’s national security advisor. “I’m sure probably the rooms were bugged, but all of that’s natural and we expected that.”

But according to a work report by the hotel’s Revolutionary Committee at the time, the Chinese hosts never relaxed their adherence to Communist ideals. If they served the VIPs in the U.S. entourage adequately, they treated their working-class American counterparts extra nicely. They tried to show solidarity with the American officials’ bodyguards and camera crews, and during meals, they chose to serve a black American first because they believed that he was a member of the oppressed class.

After 30 years, times have certainly changed. Now anyone with $3,000 can spend the night in Nixon’s old suite and flaunt his class privilege as he wishes. Given this, it’s hardly surprising that no one could stop the destruction of the xiao litang, or “little auditorium” where Nixon and Chinese Premier Chou En-lai took a major step toward diplomatic normalization.

But it’s not the first time that the hotel has been remade by the forces of history.

In the early 1900s, a European banker built the original structure as a mansion for his family. In 1959, the Communists tore that down to make way for a bigger, simpler conference hall. It housed that year’s Communist Party Congress headed by Mao and later played host to the Nixon entourage.

Those honors were not enough, however, to save it from the whims of China’s new market economy. In the late 1990s, the hotel needed room to expand so it could upgrade to five-star status. But its two landmark high-rises enjoyed historic preservation status and couldn’t be touched. So the little auditorium in the heart of the hotel grounds was tagged to go.

“The old architects were against tearing it down,” Qiu said. “We are a state-owned enterprise. But we can’t afford to ignore market demands.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.