Enron Insider Accuses Boss

- Share via

Enron Corp.’s former chief financial officer, Andrew S. Fastow, was implicated by an associate Wednesday in a series of criminal schemes to profit from Enron’s off-the-books partnerships.

Although Fastow has not been charged with any crimes, his role was outlined in a plea agreement with former subordinate Michael J. Kopper, 37, who admitted to wire fraud and money laundering. Kopper agreed to forfeit $12 million in profits and cooperate with prosecutors.

Fastow, Kopper and others pocketed millions of dollars through three partnerships that did business with the energy giant, including a previously undisclosed deal that cloaked Enron’s ownership of lucrative wind farms in California, according to papers filed in U.S. District Court in Houston.

Federal authorities said they will seek to seize $23.6 million that they say Kopper passed on to Fastow’s family and others, as well as a nearly 12,000-square-foot mansion Fastow was building in a Houston suburb, through civil forfeiture proceedings.

“We will chase the money and seek to get it back,” vowed a senior Justice Department official who asked not to be identified. “This money is treated as tainted.”

Court documents also show that Fastow’s wife, Lea, was paid $54,000 as an administrative assistant in one of the questionable partnerships. One legal expert said federal authorities may be applying pressure on Fastow by threatening prosecution of his wife.

But the Justice Department official said there is not believed to have been any discussion at this point of bringing criminal charges against Lea Fastow. A spokesman for Fastow declined to comment.

Experts said the plea bargain with Kopper is a significant advance for the government because he can help prosecutors build a case against Fastow, who is believed to have orchestrated the off-the-books partnerships that lay behind Enron’s disintegration.

“This is a substantial break for our investigation,” said Leslie Caldwell, head of the Justice Department’s Enron task force. “... When someone agrees to cooperate, essentially all of the knowledge they have becomes our knowledge.”

The case may go a long way toward cementing Enron critics’ allegations that the firm’s partnerships were fraudulent entities all along. Key former executives have insisted that the partnerships served legitimate purposes.

In court papers, prosecutors alleged that Fastow, 40, and Kopper deceived investors in the formation and operation of three partnerships from 1997 through July 2001. The details of two of them, known as Chewco and Southampton, had previously been made public. But the third, RADR, contained new details about how the two men went to great lengths to disguise wrongdoing from government regulators and investors.

The partnership was formed to mask Enron’s control of electricity-generating windmill farms in California. The scheme involved outside investors buying stakes in the farms, according to court papers. Unknown to investors, Fastow lent money to Kopper, who in turn lent money to personal friends to acquire their stakes.

In a three-year period, the investors earned about $2.7 million, and when the deal was later unwound and Enron bought back the farms, they made an additional $1.8 million, according to the filing.

In a maneuver that occurred in other transactions, the outside investors transferred some of their profits back to Fastow, Kopper and members of their families, according to the document.

The court papers also offered hints as to the government’s strategy for pursuing Fastow.

One former prosecutor, for example, said the mention of Lea Fastow in court papers may be designed to send a message to Fastow that his wife will be charged if he does not cooperate.

When junk bond king Michael Milken struck a plea bargain with investigators in the early 1990s over insider-trading allegations, he agreed to plead guilty to securities-law violations in part to shield his brother, Lowell, from prosecution

Fastow “now has to make a Michael Milken-type decision,” said Jacob Frenkel, a former prosecutor now in private practice in Washington. “It’s possible the message to Andy Fastow is, ‘tick, tock, time is running out’ ” to make a deal.

The government may also have wanted to send a signal that it has extensive evidence against Fastow and would agree to a plea arrangement only if it carried strong penalties, some experts said.

The court papers filed Wednesday left open the question of the government’s strategy for pursuing Jeffrey K. Skilling, Enron’s former chief executive, and Kenneth L. Lay, its onetime chairman, who were not mentioned. That was due in part, experts said, to prosecutors not wanting to tip their hand about the evidence they have gathered.

Of the $12 million Kopper has agreed to pay, $4 million will go to the Justice Department and $8 million to the Securities and Exchange Commission. The money will be placed in a court registry and eventually go toward reimbursing investors, officials said.

Besides the money being sought from Fastow and his family, the government revealed that it is seeking to seize assets of other former Enron employees, including Ben Glisan Jr., Kristina Mordaunt, Kathy Lynn and Anne Yeager. It also seeks $500,000 from Fastow’s brother, Peter.

Glisan is the former treasurer of Enron who reportedly helped set up partnership deals with Fastow. Mordaunt is a lawyer who worked for Fastow and then as general counsel of Enron Broadband. Enron said Mordaunt was fired last year because she invested in partnerships without the knowledge of top Enron executives.

Glisan and Mordaunt reportedly reaped huge windfalls from Southampton investments.

Lynn was an Enron vice president who left Enron last year. And Yeager was identified by Enron as a former “non-officer employee” who left the company but had invested in partnerships while working for Enron.

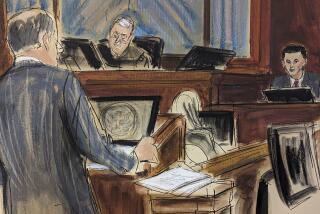

In U.S. District Court in Houston on Wednesday, Kopper told U.S. District Judge Ewing Werlein Jr. that he understood the charges against him. He also disclosed that he has seen a psychologist in the last year for stress-related anxiety.

After the hourlong hearing, Kopper’s lawyer, David Howard, said his client hopes his admission of guilt and repayment of funds “demonstrate his deep regret for his own conduct. He apologizes to all those whose lives have been affected by what he did.”

The plea agreement exposes Kopper to a maximum of 15 years in prison. Prosecutors will recommend a more lenient sentence if he cooperates as promised, but they said the final determination on sentencing will be up to the judge.

Also Wednesday, Kopper settled securities-fraud charges brought by the SEC. He neither admitted nor denied the charges but agreed to be permanently banned from working as an officer or director of a public company.

With the plea agreements from David B. Duncan, lead Enron auditor for accounting firm Arthur Andersen, and now Kopper, authorities appear to be following a carefully calculated plan to strike in short bursts, moving closer and closer to the center of Enron’s operation and earning the cooperation of key figures as they go.

The Justice Department has been criticized for what some contend is the slow pace of the Enron investigation, but prosecutors contended the case is moving relatively quickly.

“When we get to a point at which we have a case to bring that’s a significant case, we bring the case, but we do so in a manner that is professional, and we make sure that we have a case that we can sustain in court,” said Michael Chertoff, head of the Justice Department’s criminal division.

Though authorities would not comment on their next target in the probe, the senior Justice Department official said: “If and when we are willing to charge other people, we will do it....I see ourselves moving ahead aggressively and energetically in this case.”

Enron was the nation’s seventh-largest company before collapsing in bankruptcy last Dec. 2.

Hamilton reported from New York and Lichtblau reported from Washington. Times researcher Lianne Hart in Houston and staff writers Nancy Rivera Brooks and Lisa Girion in Los Angeles contributed to this story.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.