Stem Cell Therapy May Help Multiple Sclerosis

- Share via

Stem cell transplants, first developed to treat blood cancers, may halt the progression of multiple sclerosis, researchers reported Tuesday.

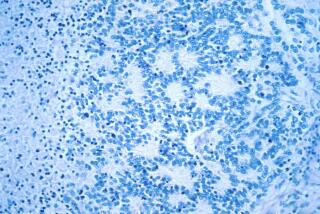

Most scientists believe multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disorder. A victim’s immune system attacks nerve fibers in the brain and spinal cord, destroying an insulating layer called myelin.

People with the disease suffer pain, have difficulty controlling their muscles and experience cognitive problems.

But a study from the University of Washington Medical Center in Seattle suggests that obliterating a person’s immune cells and then growing a new set by using the patient’s own stem cells might prevent the disease from getting worse.

Dr. George Kraft, director of the university’s Multiple Sclerosis Research and Training Center, presented results of the study Tuesday at the American Academy of Neurology meeting in Denver.

Scientists have known since the 1950s that suppressing the immune system reduces the progression of MS. But “if that were the end of things, the patient would die” because the absence of a working immune system would leave the way open to deadly infections, Kraft said. The technique has “always been in the back of our minds, but you couldn’t get up to a therapeutic level because of the toxicity.”

To avoid that problem, the researchers use stem cells. Nearly all cells in the body have a specific function--blood cells cannot become muscle cells, nerve cells cannot become skin cells and so on. By contrast, the cells of an embryo are unspecialized: They can develop into many different types of tissue. Stem cells, which in adults are mostly found in bone marrow, retain that flexibility.

In the research, doctors gave the patients an injection of growth factor to send stem cells from the bone marrow to the bloodstream. The doctors then harvested the stem cells by drawing the patient’s blood and filtering it, keeping the stem cells and discarding immune cells that might perpetuate the disease.

“We’re trying to prevent the reintroduction of the disease,” said Richard Nash, a transplant physician at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. He helped develop the procedure used in the research.

Once the stem cells were harvested, researchers used radiation, chemotherapy and antibodies to wipe out the patient’s immune system.

Finally, the stem cells were reintroduced to the patient’s bloodstream, where they turned into new immune system cells. The level of immune cells recovers within nine days, Nash said.

The researchers, working with transplant physicians in different centers, followed 26 patients for an average of 15 months after the procedure, called autologous stem cell transplantation. In more than 75% of the patients, their disability stopped getting worse after the treatment, Kraft said.

There is, however, no guarantee that the immune cells won’t begin attacking nerve fibers again in the future, he noted.

Researchers are not sure what triggers the immune response that causes MS, said Dr. Michael Racke, associate professor of immunology and neurology at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Genetic and environmental factors likely contribute. If one person in a set of identical twins gets MS, for example, the other, who has the same genetic material, has only a 25% chance of developing the disease, he explained. That is a much higher rate than a person in the general population but still not a sure thing.

The hope with stem cell transplants is that “I then become my own twin,” with a reduced chance of getting MS again, Racke said.

The procedure has risks. Some patients--about 5% to 10% in these studies--have died of infection due to immune system suppression.

Kraft limited his study to patients severely affected by MS who had not responded to other available treatments. Patients in earlier stages of the disease, who might be progressing more rapidly, will be included in future studies. A National Institutes of Health study, for example, will compare transplants with Novantrone, an FDA-approved drug to prevent relapses, said Richard Burt, director of immunotherapy at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago.