Today’s Germ War, Yesterday’s Weapons

- Share via

ATLANTA — “It’s not your mother’s smallpox,” says Dr. Robert Kadlec, physician and National Defense University professor. “It’s an F-17 Stealth fighter--it’s designed to be undetectable and to kill. We are flubbing our efforts at biodefense. We don’t think of this as a weapon--we look naively at this as a disease.”

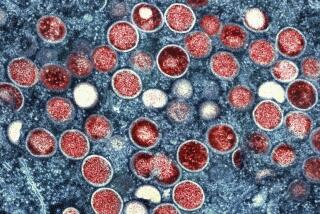

Kadlec is talking about a form of smallpox that doesn’t exist yet--so far as we know. But recent research in Australia on genetically engineered mousepox virus shows that such a Stealth-fighter agent may be simpler to create than Western experts used to think. Genetically modified smallpox adds additional terror to a weapon that’s already deadly--a weapon we now understand could actually be used against us.

As we have learned in recent weeks, terrorists have already used biological weapons on our soil: highly refined anthrax delivered in a simple but lethal way. Smallpox would be no harder to distribute: Like anthrax spores, smallpox is durable in the external environment and could easily be dried, turned into powder and enclosed in a letter. But as a weapon it’s far more frightening: Smallpox, unlike anthrax, is wildly contagious as well as lethal. The bioterrorist threat has made the U.S. government ratchet up plans to produce 300 million doses of smallpox vaccine by next year to meet the threat of a smallpox biological weapon.

But in stockpiling vaccines we are planning a campaign based on a very old war. Many in the U.S. biodefense community do not want to combat a possible new threat--vaccine-resistant smallpox--with old weapons: in this case, a smallpox vaccine that might well not work against the smallpox strain released. But government research into the best way to combat an altered smallpox is controversial.

The threat of engineered poxvirus is real. Interviews with former Soviet scientists suggest that Soviet bioweapons labs were actually close to creating it more than 10 years ago. But at this point, scientists and biodefense experts worried about resistant smallpox face a paralyzing dilemma over how to create and test such an agent. Even discussion hangs suspended.

Unlike Soviet bioweaponeers, who were trying to build more lethal agents, the Australian scientists stumbled on their results. Working on a high-tech method of mouse fertility control, they inserted a gene that produced a mammalian hormone, interleukin-4 (IL-4), into mousepox, a disease of mice that’s related to smallpox. The engineered mousepox killed most of the mice injected with it, including those mice that, through vaccination or heredity, were supposed to be immune.

“Monster mousepox,” as pox virologist Mark L. Buller of Saint Louis University calls it, kills not by changing the virus itself, but rather by subverting the mouse’s immune system. This experiment raises the specter of diabolical new biological weapons. Humanity evolved alongside certain diseases, smallpox among them, in an arms race between germs and our species. Over millennia, human populations developed resistance to particular diseases. But what if those evolved defenses--and vaccine-induced immunity, as well--could be shut down by a gene incorporated into the pathogen itself?

Sergei Popov is a Russian scientist who worked, until he defected in 1992, at Vector Laboratories, a Soviet facility in Siberia that conducted clandestine research into smallpox. He says that Vector and other Soviet labs worked with such immunosuppressive agents, synthesizing both immune peptides and the genes that produced them. They studied the effects of these peptides on animal and perhaps on human immunity; they put the synthesized genes into living viruses. They were on their way to “monster mousepox” and beyond--and this work began over 20 years ago.

Many American scientists once doubted that genetically engineered diseases could become functional biological agents. But since “monster mousepox,” even the skeptics are beginning to think again. “We believed that, given the multicomponent nature of the immune responses to viruses, it would be very difficult to engineer them to evade vaccine-induced immunity without compromising the virus’s pathogenicity,” says Peter B. Jahrling of the United States Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID). “It was a simple idea, and it was wrong. You can engineer the body’s response to the virus instead!”

Popov worked in an ultra-secret division of the Soviet bioweapons program known as “Factor,” which “dealt with small peptides and immune modulators. We started [by] making small genes to produce these peptides. The customer [the Soviet Ministry of Defense] wanted strains with new peptides” for weapons development, says Popov.

By 1981, Soviet scientists knew that viruses could be engineered to express human immune peptides. In 1984 and 1985, Vector researchers incorporated such toxins directly into mousepox and vaccinia, the smallpox vaccine virus, which is closely related to smallpox and often substituted for it in experiments.

Did the Soviets actually synthesize IL-4 to make vaccine-resistant smallpox as the Australians did inadvertently with mousepox? There is no evidence that they did, though all necessary steps were in place in their labs by 1992. And the opportunities to make this strain today may be greater than we like to think. Most biodefense experts believe that smallpox has proliferated beyond the two laboratories, one in the U.S. and one in Russia, authorized by the World Health Organization to maintain stocks of the disease. North Korea has it, and other rogue states may as well. Vaccine-resistant smallpox is now a credible threat--especially since the publication of the Australian experiment.

But U.S. experts are in a quandary over what to do about it. In a series of recent New York Times articles, reporters Judith Miller, William Broad and Stephen Engelberg revealed that the Pentagon has secretly considered creating an engineered strain of anthrax that incorporates two genes from a related bacterial species. The Defense Department is interested in testing a claim made by Russian researchers that this strain overcomes the immunity conferred by anthrax vaccine. But even discussing such testing has caused an uproar. Some experts feel the Pentagon has come close to violating the 1972 Biological Weapons Convention by just talking about it. Repeating the mousepox experiment would undoubtedly cause an even greater furor, and altering smallpox would be unthinkable.

But, especially now, in the face of ruthless terrorism, we need to know whether a weapon developed against natural smallpox can still protect us against engineered strains. The solution is not to do this experiment alone. Recent smallpox research at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta has been conducted under the auspices of the World Health Organization. Any testing of engineered strains must be conducted the same way--openly, transparently and with the full cooperation of the people who know the agent well, including the former Soviet scientists at Vector. “Secrecy is fatal,” warns John D. Steinbruner, bioterrorism expert at the University of Maryland. Doing this work openly and cooperatively is the only way to avoid the appearance that the U.S. has gone back into the biological-weapons business itself.

There are influential voices within the government that want to keep IL-4 research classified: They don’t want to make the work of bioterrorists any easier. But the genie has left the lamp. Two decades of Russian research and the widely publicized Australian experiment make secrecy impossible. If the smallpox vaccine can no longer protect the world, we need to know it, so that alternate therapies, including new vaccines and better antiviral drugs, can be developed while there is time.