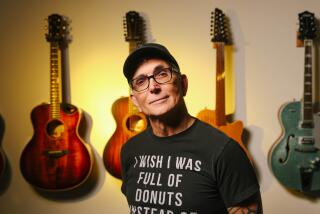

Terkel Tackles the Inevitable

- Share via

Studs Terkel does not rest easy. Since a childhood beset by ailments, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, oral historian and radio man has feared that if he falls asleep, he’ll never wake up.

To this day, when he finally lets himself doze off, he unclasps his hands and removes them from his chest. The first image he remembers of a dead person was a newspaper photo 78 years ago of Pope Benedict XV lying in state with his hands clasped across his breast.

Though he has yet to die in his sleep, he feels death closing in, feels surrounded by it, he writes in a new book. Not that he’s complaining, exactly; he knows that with his genes, at 89 he’s lived far longer than anyone would have ever guessed.

His two brothers and his father all died in their 50s. Weak hearts. In fact, it was he who found his father lying in bed dead with “his spectacles askew.” Terkel too suffers from a heart condition, and underwent quintuple bypass surgery in 1996.

But it was the death of his wife of 60 years, Ida Goldberg, in 1999 that inspired him to finally write “Will the Circle Be Unbroken? Reflections on Death, Rebirth, and Hunger for Faith” (New Press). The man who has chronicled the Great Depression, World War II, working and race relations this time compiles the oral histories of dozens of people--from gravediggers to death row parolees to cops to doctors--and their intimate thoughts of and experiences with death.

The seed for the book was planted 30 years ago during a drink at the bar of the Ambassador East Hotel in Chicago with author Gore Vidal, who suggested death as a subject.

“I stared into my drink. No bells rang,” writes Terkel. “My works had been concerned with life and its uncertainties rather than death and its indubitable certainty.”

These days, the first section of the newspaper Terkel turns to is the obituaries. The practice has led him to recite a bit of old doggerel each day:

I wake up each morning and gather my wits,

I pick up the paper and read the obits.

If my name is not in it, I know I’m not dead,

So I eat a good breakfast and go back to bed.

On a recent day, Terkel is in Los Angeles to speak at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. He is scheduled to talk with a visitor before the public conversation, but then, a slight problem. Terkel is fast asleep. But soon enough, he is ready to chat. He’s waiting in the office of Paul Holdengrber, head of LACMA’s Institute of Art & Cultures, who later introduces his literary guest this way: “He is not full of himself, but he’s full of others.”

Interviewing an interviewer, a veteran one at that, is never easy. You ask questions, hoping to head in a certain direction, but they go where they want. Terkel is no exception. Where he usually goes is back to his poignant and elegantly written 10-page introduction in his book.

It’s like one of his famous oral histories in reverse--he wrote it, now he speaks it. He repeats passages almost verbatim, and then again, minutes later, to the 300-member LACMA West audience.

He complains that people only talk about death out of grief or guilt. Instead, the end of life should be discussed openly and ideally when one is in perfect health.

“All my books in the past have been about experiences people have had,” he says. “But what is the one experience none of us has had, but we all have?”

Before the question can be posed, he rejects the notion that the topic is necessarily depressing. A sober contemplation of death, he says, enriches an appreciation of life. “The book, by the way, is about life, not about death,” he says. “Life is finite and, because it is, each day is so precious. It’s about L-I-F-E. That’s the theme of this book.”

Still, there are dramas that play best for an audience of one. Without prompting, Terkel, a former soap opera actor, details a few of his childhood illnesses. He was very sickly, he says. He had asthma, he says. He had mastoiditis (a serious middle-ear infection that can cause deterioration of the mastoid bone of the skull).

“Here,” he says, rotating in his chair and peeling back his ear. “Put your finger there.”

There is some hesitation.

“Really, go ahead. Put it in there,” he insists. “That’s a deep hole, isn’t it?”

It’s true. The space could accommodate a large marble. “I didn’t know if I was going to make it as a kid,” he says.

Moments later, Terkel takes his chair upon the small stage to a standing ovation in LACMA’s fifth-floor penthouse room. In short order, he rattles out his feelings on the key topics of his book.

Does he believe in an afterlife?

“I envy those who believe in one. It brings a great solace,” says Terkel, who defines himself as an agnostic--or cowardly atheist. All the same to him. “But as Gertrude Stein said, I believe ‘there is no there there.’ Nada. “

Is he afraid to die?

“At the age of 89, I’ve had a pretty good run,” he says. Then he stops to quote Winston Churchill, who was reputed to have replied to the query, “Who would want to live to be 90?” with, “Everyone who is 89.”

Terkel manages to sneak in other light moments. He tells how years ago a public librarian from Atlanta had complained to Moral Majority types about a new book called “Working Studs” by someone named Terkel. The mistaken reference to Terkel’s book “Working,” a wildly popular oral history of ordinary working men and women and how they perform their jobs, draws gales of laughter.

“I knew it was going to be a bestseller after I heard that one,” says Terkel, whose given first name is Louis.

Inevitably, a conversation centered on death turns to Sept.11. It should go almost without saying that those “barbarians” responsible should be brought to justice, he says. Still, the attacks cast a new light upon America’s once indomitable position within the global village, an awakening of sorts for the better. “We’re vulnerable and thus being vulnerable, we’re human,” he says.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.