Having Fun With Some Building Blocks

- Share via

NEW YORK — “In the next century it is highly possible that . . .” reads the text on an exhibit wall in the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan. Three large electronic tickers finish the sentence with a variety of predictions. “Parents will be able to choose traits and characteristics for their children ranging from eye color to athletic and musical ability,” says one. “We will each carry our individual genome on a wallet-sized computer card,” reads another. “We will be able to clone and propagate any species, even endangered ones,” says a third. The messages flow by in a continuous red stream like the news flashes filling Times Square, perhaps a nod to the headlines of the future.

“The Genome Revolution” provides one of the most telling examples of the effort required to keep pace with one of the most rapidly expanding fields of science.

“It truly is a revolution,” said Rob DeSalle, the exhibit’s curator and co-director of the museum’s molecular laboratories. “It’s a revolution when you know that it’s going to affect your life and your children and your children’s children. And it’s essential that people understand it.”

Museum scientists say they recognize the monumental task of bringing a wary and often ill-informed public up to speed on the vast array of dangers and promises posed by this scientific field. But DeSalle said the recent acceleration of the research is demanding difficult decisions, regarding not only genome science, but also its associated ethical, social and legal implications.

DeSalle conceded that more of the exhibit focuses on personal choices than on societal issues, in the hope that visitors will relate to vital scientific concepts that often elude much of the general public. A recent survey developed by the museum in conjunction with the polling organization Harris Interactive found that 78% of 1,000 randomly selected Americans could correctly identify the gene as the basic unit of hereditary information. But only 29% had ever heard of the Human Genome Project, the massive effort to sequence the entirety of our genetic make-up. The museum hopes to change that with the most comprehensive exhibit yet on genomic research.

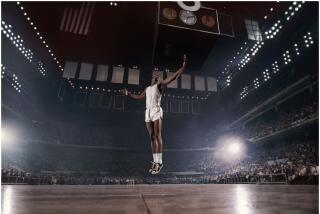

Although much of the exhibit is forward-looking, it also includes some historical references, including the original foot-high DNA model used in 1953 by James Watson and Francis Crick to explain the molecule’s newly discovered double helical structure. Nearby, a pair of gold shoes used more recently by Olympic sprinter Michael Johnson symbolize how genes can affect athletic performance--up to a point.

The exhibit also provides a study in contrasting dimensions, from a small vial containing the stringy white DNA strands of several anonymous donors to a display depicting the 140 volumes of Manhattan white pages that would be the size and number of publications required to print out all 3.2 billion letters of our genetic material.

A Challenge to Keep Pace

With New Developments

The ever-changing field of genomic research has provided more than a few headaches to the exhibit’s developers, however. Last fall, staffers wrote much of the exhibit text using as their reference the estimated 3.5 billion “letters” of DNA and 100,000 genes contained within each copy of a human genome. With the last of the genomic sequencing completed this spring, scientists revised those numbers to an estimated 3.2 billion letters of DNA and around 32,000 genes. The museum has had to follow suit.

“We made sure that everything we have on the walls will stick on the walls,” DeSalle said. The museum may also have to reserve some wall space for new developments.

“Before this exhibit closes in January of 2002, there is a strong possibility that a human being might be cloned, so we have to be abreast of that and prepared to address that if it happens,” DeSalle said. The exhibit already has a section focusing on the implications of cloning everything from a family pet to a family member, including a model of Dolly the sheep, the first cloned mammal, which made headlines four years ago. Polling stations compare visitors’ opinions with national survey results, which show 86% of Americans reject the cloning of a favorite pet and 92% oppose the cloning of a favorite person.

At another station, a digital camera and an interactive display screen provide a simple lesson in genetic relationships. The onlooker may select an animal or plant to be compared with--such as a chimpanzee, mouse, roundworm or rice, among others--and a vertical bar then reveals the extent of shared genes, such as 98% between chimps and humans, and 15% between humans and rice.

Elsewhere in the exhibit, a series of seven illuminated blue panels explains the physical nature of DNA and its role in directing cellular activity. Another panel near a glowing DNA helix explains that mutating a gene called INDY (I’m Not Dead Yet) doubles the average life span of the fruit fly. Visitors can twist the rungs of the glowing helix to discover other mutations that wither the fly’s wings or cause a leg to sprout from its head.

Some of the genetically modified plants and animals under development around the world are also discussed in the exhibit, such as cotton plants engineered to produce a “denim blue” hue that would reduce the need for dyes.

As visitors leave, cameras project their images onto large screens. Each image is converted into a stylized version consisting entirely of small green A’s, red Ts, yellow Gs and blue Cs--a final reminder of the stuff we’re all made of.

* “The Genome Revolution” runs through Jan. 1 and is included in the general admission price for the American Museum of Natural History. For more information, call (212) 769-5100 or visit https://www.amnh.org.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.