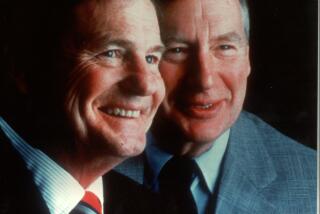

Erik Barnouw; Told Broadcasting’s History

Erik Barnouw, considered the dean of media historians for a definitive, three-volume history of broadcasting, died Thursday in Fair Haven, Vt. He was 93.

Barnouw was both a participant in and an astute analyst of much of the history of radio and television in the 20th century. He wrote early radio and television dramas, made a highly praised documentary about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, founded the film, radio and television department at Columbia University, and chaired the broadcast division of the Library of Congress.

He also wrote a dozen well-received and provocative books, including an authoritative trilogy called “The History of Broadcasting in the United States,” published between 1966 and 1970. Critic John Leonard once called it the work “everybody who writes about television steals from.”

Born in The Hague, Holland, in 1908, Barnouw immigrated to the United States in 1919. He grew up in New York and attended Princeton University, where he earned the acclaim of his peers as a playwright and lyricist.

He might have graduated to Broadway had the year not been 1929. Instead, he took a job with an advertising agency, helping to supervise radio shows sponsored by its clients, including “The Camel Quarter-Hour,” a live variety program.

From there he segued into producing and directing radio dramas such as “True Story Court of Human Relations” and “Bobby Benson of the H-Bar-O Ranch.”

He quit broadcasting in 1937 when he was asked to teach a course on radio at Columbia. His students included a young Bernard Malamud and the novelist Pearl Buck, who signed up for his radio writing course under an alias. By the early 1940s, Barnouw also was working as an NBC script supervisor at Rockefeller Center. Then he headed to Washington to oversee the Armed Forces Radio Services’ education division.

After World War II, he produced a series of syphilis awareness spots that Columbia’s new president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, liked so much that he helped persuade station managers around the country to air them.

In the 1960s, after completing a book about India’s cinema, he was commissioned by Oxford University Press to write the trilogy on broadcast history.

The first volume, “A Tower in Babel,” traced radio from its infancy until 1933. The second book, “The Golden Web,” examined the golden years of radio from 1933 to 1953. The final installment, “The Image Empire,” covered the rise of television and its impact on American culture.

Barnouw’s background made him a formidable critic of commercial television. He said the advent of ratings in the mid-1950s was “one of the worst things that happened” because it led to standardized programming and quashed the medium’s sense of adventure.

In 1970 he attempted to sell a 16-minute documentary, “Hiroshima/Nagasaki, August 1945,” to the networks. It was a departure from most television coverage of the atomic bombings, which until then had concentrated on the physical destruction of the cities.

To show the human devastation, Barnouw obtained Japanese newsreel footage that had been kept under seal by American military authorities until the late 1960s. It would prove shocking to Americans, few of whom had seen scenes of Japanese doctors treating the horrific burns and radiation disease of the bomb victims.

Of the networks, only NBC showed some interest, offering to broadcast part of the film if it could find a “news hook.” (“We dared not speculate what kind of event this might call for,” Barnouw later said.)

The Boston Globe denounced the networks for turning down the movie, which it called “the most important documentary” of the century. It eventually was aired by National Educational Television, the forerunner of PBS, on the 25th anniversary of the Hiroshima bombing in 1970. It earned the network one of its largest audiences.

Another notable work by Barnouw was “The Sponsor: Notes on a Modern Potentate,” published in 1978, in which he examined the influence of advertisers. His view was gloomy. One example concerned a 1950s dramatization of the Nuremberg trials, sponsored by a natural gas association. The trade group insisted that all references to “gas” (as in gas chambers) be excised from the script.

Critic John S. Rosenberg, writing in the Nation, said the book made it “abundantly clear that the very purpose of the programs--a purpose that governs them from inception to airing--is to bring us to the commercials.”

Barnouw also wrote “The Magician and the Cinema,” a 1981 book that drew a link between the demise of the great 19th century magicians and the rise of another kind of optical illusion: film.

In 1996 he published “Media Marathon: A Twentieth-Century Memoir,” which consisted of a series of character sketches of interesting people Barnouw had encountered over half a century of involvement in broadcasting.

Among his many honors were a Peabody Award in 1944 for an NBC radio series, “Words at War,” a George Polk Award in 1971 for “A History of Broadcasting in the United States,” and the preservation and scholarship award of the International Documentary Assn. in 1985.

The Organization of American Historians in 1983 named an award in his honor to recognize outstanding reporting or programming on network or cable television or in documentary film. The first recipient was documentarian Ken Burns.

Barnouw is survived by his wife, Betty, of Fair Haven; a son, Jeffrey, of Del Mar, Calif.; two daughters, Susanna Gilmore of Benson, Vt., and Karen Barnouw of Rutland, Vt.; a grandson; a great-grandson; and a sister.

Contributions in his memory may be sent to Erik Barnouw Award, c/o Organization of American Historians, 112 N. Bryan Ave., Bloomington, IN 47408.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.