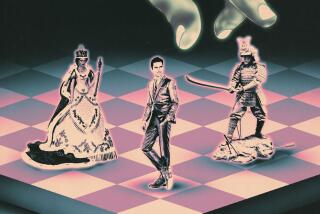

Duels, Deals and Down-and-Dirty Politics

- Share via

One of the hardest things for a historian to capture is the utterly commonplace. American historians of 2250 will, God willing, still inhabit a secular republic, in which publicity, public opinion and the personal histories of would-be leaders still play a role. But when they look back from then to now, will they understand the function of TV pundits Chris Matthews and Jeff Greenfield? Of push polling and focus groups? Of the log cabin myth and the persistence of political families (Bushes, Clintons, Kennedys)? Will they notice what we see every day when we look in the mirror?

In “Affairs of Honor,” Joanne B. Freeman examines the political culture of the founding period from 1789, when the new government established by the Constitution went into effect, until the first decade of the 19th century. The men who dominated that era--George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison--have hardly faded away. Only the actors of the Civil War and the Greatest Generation have an equivalent hold on our minds. But, Freeman argues, we ignore a lot about the founders that is in fact quite odd, and we casually impute to them much that they would have found strange. Respect breeds a sense of familiarity, which she believes is spurious. “Affairs of Honor” is an attempt to recover the lost templates of their political life.

The most important thing to realize about the politics of the founding period is that there was, at first, no two-party system; parties are not mentioned in the Constitution. In Federalist No. 10, Madison discusses factions but only with the wariness of a scientist handling germs in a lab. Washington’s farewell address, which was ghosted by Hamilton, warns against party spirit. Yet all three men, by the late 1790s, had become partisans in the emerging two-party system: Washington and Hamilton of the Federalists, Madison of the Republicans (the ancestors of today’s Democrats).

Yet these nascent parties were not like the organizations we know today. For one thing, none of the founders recognized the legitimacy of their rivals. Each called the party of his opponents a host of abusive names and expected that the party he disliked would wither away. Both proto-parties were unstable alliances, prone to sudden shifts and hence riven with mutual suspicion. When the Republican Jefferson, who had lost the election of 1796 to the Federalist John Adams, offered what would now be routine civilities to his victorious rival, his supporters felt betrayed. One of them called Jefferson’s remarks “a damned time-serving trimming speech.” Party loyalty and the ethics of partisan combat developed only after years of trial and error. “[N]ational politicians did not march into party formation with their eyes open,” Freeman writes. “[T]hey backed their way into it one decision at a time.”

Instead politics was conducted by what Freeman calls “political fighting units,” which were led by prominent local figures with national reputations and consisted of their immediate supporters and attendant journalists. The supporters ran errands while the journalists made propaganda. The leaders held them together with the usual mix of appeals to interest and ideology. But such leaders also brought to bear their honor as gentlemen. To his followers, a leader’s honor made him someone to look up to. To other political chieftains, it guaranteed that his promises would be kept.

But if honor conferred stature and power, tearing down the honor of a rival conferred advantage. Freeman’s book surveys the various ways in which honor was attacked and defended. One method was gossip. “Beneath the political superstructure created by the Constitution,” writes Freeman, “a subterranean politics of intrigue flourished.” In 1793, one of Hamilton’s friends wrote to him, in a lurid phrase, that “the throat of your political reputation is to be cut, in Whispers.” One of the most skillful cutthroats was John Beckley, clerk of the House of Representatives. “Because he constantly shuffled congressional papers, he knew the handwriting of the representatives”; because Beckley was also familiar with the printers, he could “prove authorship of anonymous pamphlets....”

Many of Beckley’s tidbits found their way into the “Anas,” a collection of gossip that Jefferson compiled, arranged and polished until the end of his life. Pamphlets and newspapers were another arena of disputes over honor. Americans were great readers. In 1790 the post office delivered 500,000 newspapers to a population of 3.8 million; public readings boosted the audience still higher. American journalism has never again hit the highs that it hit in the late 18th century, when Thomas Paine’s “The American Crisis” appeared as a pamphlet and “The Federalist Papers” ran, four times a week, in New York newspapers. More common, however, were screechy political attacks, conducted without a pretense of objectivity. Talk radio looks good by comparison.

Gossip and attack journalism are still with us; what has vanished is the final resort of the honor system, the duel. The 1804 duel in which Vice President Aaron Burr killed Hamilton is famous (to give it contemporary resonance, imagine Dick Cheney killing Robert Rubin, Treasury secretary under former president Bill Clinton). But the duel was not freakish. When the honesty or the honor of a gentleman politician was impugned, the mechanism of the duel was a last option. Most duels, Freeman points out, “were intricate games of dare and counterdare” that stopped short of the dueling ground. But many had lethal consequences, which the public accepted as a matter of course. The death of Hamilton destroyed Burr because powerful men in both parties, Federalist and Republican, had been out to get him beforehand. But Brockholst Livingston, another politician who killed a man in a duel, was appointed by Jefferson to the Supreme Court.

Freeman calls herself an “ethno-historian,” and “Affairs of Honor” carries some of the stigmata of that discipline. Many fine tidbits float in a non-narrative whirl; readers coming to the period for the first time may feel at sea. But often enough, along comes a figure she likes, and her narrative finds a firmer focus. Her heart clearly belongs to Hamilton, the illegitimate immigrant, so conscious of having made it and so anxious about losing it all. Freeman has also brought out “Alexander Hamilton: Writings,” a stout one-volume edition of his greatest hits, for the Library of America. This is a major public service. Hamilton’s contributions to “The Federalist Papers” are in every bookstore, but his many other writings have not been available in a handy format for decades. Here one finds the “Report on Manufactures,” his vision of America’s economic future, and his pamphlet on the Reynolds Affair, the first great American sex scandal. Here is his teenage account of a hurricane in St. Croix that prompted his neighbors to send him to the mainland to be educated. One also finds the tough, shrewd analyses of foreign policy that are so relevant in our time of troubles. Anyone interested in politics, finance, diplomacy, history or the fascination of a strange all-American life will want to have this Library of America volume.

Freeman also does well with Hamilton’s nemesis Burr. She nicely captures Burr’s cold soul and shows that the reason so many of his peers came to distrust him was, paradoxically, because he felt that a politician could make a career based on honor alone, unballasted by programs or political principles. Burr, the first practitioner of triangulation, maneuvered himself off the map of American politics.

If there is a flaw in Freeman’s argument, it is the assumption that the politics of honor was replaced by a full-blown and monolithic party system: “[T]here was only one way out of this endless battle of reputations: the anonymity of party warfare.” But the American party system got off to an exceedingly slow start. The Federalists vanished as a national force in 1816, leaving Jefferson’s heirs to quarrel among themselves. The Whig Party, which emerged in the 1830s to combat Andrew Jackson, restored a bipolar system. But it too vanished, after only 20 years. Meanwhile, the Antimasons and the Know Nothings came and went. Political dueling also continued for decades (Henry Clay and John Randolph, of the post-founding generation, had a famous exchange of shots in 1826).

The primacy of the Democrats (nee the Republicans) and the modern Republican Party was fixed by the Civil War: Death gets people’s attention. Prohibition, populism and socialism beat against this two-party system in vain. The withering of party machines, replaced by polling and advertising, and the rise of nonpolitical corsairs such as Ross Perot or Ralph Nader may be a sea change. Or they may be mere squalls, which the two-party system will weather. Whichever turns out to be true, it is useful to know that the two-party system is not made of brass. “Affairs of Honor” is a good case study of its mutability.

*

Richard Brookhiser is the author of the forthcoming “America’s First Dynasty: The Adamses 1735-1918.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.