His Life Is in His Instruments

- Share via

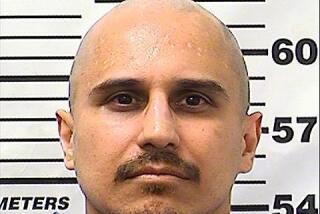

Deep in Modjeska Canyon, Guillermo Martinez waits patiently for new drums to be born.

“You create drums by feel,” said Martinez, 39, an instrument maker skilled in Native American traditions whose ancestors are Tarascan, an indigenous people of Mexico. “You soak the skin for the drum’s head to make it flexible and then you can’t play the drum for a day or two while it dries,” he said. “You’re really like a woman who’s pregnant. You can’t hear your child or really see what it looks like until it’s ready.”

A tall man with an unassuming aura, Martinez is known for his artful instruments. He makes about 150 flutes and the same number of drums a year plus a variety of whistles and rattles. He sells them and also performs Native American songs and dances at powwows, cultural festivals and Native American markets around the country, including the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles.

“My instruments are tools for connecting people to their spiritual paths,” Martinez said. “That means you never make an instrument when you’re angry--whenever you’d play it, it would project anger. When I teach instrument-making I tell my students, ‘You can either take the Red Road, the path of creation, or the Black Road, the path of darkness and hate.’ It’s all vibrational. You carry the vibrations of your instrument inside yourself.”

Sitting and talking on the patio of his home workshop, tucked in the wooded canyon in central Orange County, Martinez deftly carved a 1-inch oval in a double flute of Alaskan yellow cedar. A half-dozen clay flutes baked in his kiln. A pile of gourds spilled across the dirt of his backyard, smaller ones destined for rattles, larger ones for drums.

“Nice fit,” Martinez murmured as he set a small decorative piece inside the hollowed-out oval of the flute. “It’s easy to take the wood away--but you can’t put it back.” Martinez also makes effigy flutes in cedar, carved with the likeness of Sand Hill cranes, in the Lakota style of the 1800s. A “visionary flute” is fashioned like a green serpent, sporting thick plumes of feathers and sharp teeth, based on a dream he had.

Higher-pitched flutes start with pieces of wood 14 to 30 inches long. Martinez uses 30- to 40-inch boards for larger, lower-toned flutes.

A wooden double flute can take five to seven days to make, using a variety of vintage and contemporary tools. There are chisels for wind ways--the small grooves that connect the flute’s two chambers--plus Japanese saws to angle the mouthpiece, native Alaskan woodworking tools to shape it, a block plane to hone the flute’s body and an 80-year-old spokeshave for a final, overall rounding.

Each instrument has its rituals. Sometimes Martinez cleans gourds meant for drums in the creek behind his house. Sometimes he gathers elderberry wood for flutes from nearby hills. He may carve his drums ornately over the course of a month or two, as he did with a tall Mayan huehuetl. In an hour and a half he can fashion a smaller hand drum, using a modified laced style he learned from a Cree Indian in Alaska.

But his ocean drums capture the attention of listeners the most. Martinez crafts them from gourds or wood frames--softly painted, with burned-in designs or inlaid with stone or shell. Filled with 1,500 or so mixed glass and metal beads, these drums sound like waves storming Big Sur or lapping Baja beaches as musicians dip and tilt them at various angles.

“The Mayans used to fill their drums with jade and turquoise marbles,” Martinez said. “But that would be way too expensive today.”

By tradition, each material Martinez uses carries the energy of its place of origin. “If I make a flute from clay dug in Arizona, it carries that essence,” he said. “Each deerskin I use carries the essence of that particular deer. It may even carry its real scars, from fighting or running through the bramble in the woods.”

Born in Jacona, Mexico, Martinez grew up in the San Fernando Valley. He began making drums and rattles when he was 18. In 1988 he apprenticed with Klinquit instrument makers in Alaska. He met his first mentor, Xavier Quijas, at a Rose Bowl swap meet in 1989. Quijas taught him to make ocean drums. From his second mentor, Agustin Rodiles, Martinez learned pre-Columbian woodcarving.

Still, his passion is sitting at his open-air workbench, “sending peace, love and compassion” from his heart to his hands, finding the music in the wood.

“This is it,” he said of his art. “Most people spend almost a lifetime trying to figure out what they want to do in life but I found it relatively early. I had the support of friends and [family]. In my instruments are my teachers, my loves, my heartbreaks--you could say my whole life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.