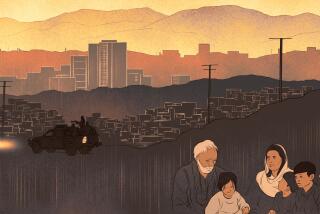

Afghan-Born Pilot Senses Fear, Then Gives a Gentle Lesson

- Share via

He’s a veteran United Airlines pilot and he couldn’t be prouder of what he calls his “sacred mission”: ensuring the safety of the passengers he flies across the world.

But in these wary days he’s afraid those very passengers might hear his name and panic.

So he never mentions it.

“I’m very careful not to announce that my name is Mohammad Daoud, because I’m sure that they would feel uncomfortable, which is sad for me,” the Afghan-born pilot said softly on a recent morning, resting in his Malibu living room after six days of flying.

“It’s very sad to hide your name from the passengers that you’re protecting.”

It’s not just that his name is Mohammad. Daoud is also a Muslim. Since his first day back at LAX after Sept. 11, he’s seen the way others now process these facts, how the person he is gets lost.

At first, the soft-spoken, gentle-eyed father of three clung to a belief that Americans simply needed to learn.

On his first post-Sept. 11 flight out, the captain--a man he’d never flown with before--seemed jumpy. Here and there on the flight to Hong Kong, as the two pilots completed the routine things--monitoring systems, talking to Air Traffic Control--the pilot commented on the looming U.S. counterattack, about the hijackers.

“He thought that the whole Muslim world hates America,” said Daoud, a first officer. “That was his feeling.”

There wasn’t time on the flight to chat much. But the next morning at breakfast, Daoud told the pilot that he was from Afghanistan and that he was Muslim. He began to describe what that meant.

A short layover stretched to four days when the return flight was canceled. So Daoud’s gentle lesson about Afghanistan and Islam became a more thorough tutorial, continued over lunches and dinners, shopping and the nightly news.

“He was very apprehensive about what was going on at the time. The war hadn’t started. The bombing hadn’t started,” Daoud said. “The headlines were all about the people who did it, what they believed in.”

“And when I explained Islam to him, when I explained how a majority of Muslims are not these radical Arab terrorists, he said, ‘I feel much better.’ ”

Daoud tries not to take things personally. It is hard.

There was the story he heard from a gate agent about how a pilot had delayed a flight by refusing to fly with a co-pilot who came from “somewhere in the Middle East.”

Or the time he watched the flight attendants make comments about the Muslim meals some passengers had ordered, and he thought he saw something nervous in their body language.

Soon after he returned to LAX after Sept. 11, a flight attendant told him that another pilot had made it clear that he was “not very thrilled” about flying with Daoud.

It hurt most because Daoud, 49, believes fiercely in America and its freedoms. Chosen from more than 1,000 applicants to become a pilot for Afghanistan’s state airline, he learned to fly in the 1970s, in Miami, New York and Long Beach.

But in 1980, after the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, he turned a regularly scheduled Ariana Afghan Airlines flight to Frankfurt, Germany, into a mass Afghan defection.

On the plane, after a stop in Istanbul, the crew announced the plan over the PA system.

“We made an announcement that if anyone wants to join us, we are not going back and this is a defection and we are condemning the Soviet invasion, and this is a liberation flight.”

Seventy Afghans defected in one fell swoop, he said. Germany and the United States offered Daoud political asylum. He chose America.

For a time, he had to drive a cab in Washington. Watching each plane take off from National Airport, “my heart was going with it. Every takeoff, my heart would fly.”

Fear can be overcome, he said.

“The biggest fear people have of each other is that they don’t know each other, the fear of not knowing. Once you get to know people--even if their name is this or their religion is that--they’re not as strange or dangerous.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.