A Fluke of Timing

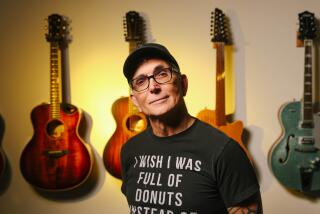

“This song was about the decline of the American spirit,” says John Ondrasik, leading his band Five for Fighting onstage at the El Rey Theatre recently. “But that doesn’t seem appropriate anymore, so I wrote new lyrics for the end.”

Indeed, “The Last Great American,” as heard on Five for Fighting’s “American Town” album from 2000, is an Ayn Rand-like allegory of an earnest man who, unable to fight a national tide of moral and cultural decay, finds the only way to stay true to his values is to bury himself alive.

For the record:

12:00 a.m. Dec. 5, 2001 FOR THE RECORD

Los Angeles Times Wednesday December 5, 2001 Home Edition Part A Part A Page 2 A2 Desk 1 inches; 17 words Type of Material: Correction

Album title--A story in Sunday Calendar on Five for Fighting listed the band’s album incorrectly. It is “America Town.”

For the Record

Los Angeles Times Sunday December 9, 2001 Home Edition Calendar Page 2 Calendar Desk 1 inches; 18 words Type of Material: Correction

Album title--A story in the Dec. 2 Sunday Calendar on Five for Fighting listed the band’s album incorrectly. It is ‘America Town.’

But in the new version, rewritten following the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, just as the hero is about to pull the lid down on his coffin, a calamitous turn changes the course of action:

The funeral pyre was s hattered

And the world became undone ...

[And] through the smoke and morning sun

Stands the Last Great American .

Arguably, many of the songs on the album--reflecting Ondrasik’s often discouraging struggle to build a music career and stay true to his values through most of his adult life--would be candidates for rewriting now. The title song, for example, is about what he saw as stifling complacency in the nation. “Love Song” is a sad tale of divorce. And “Superman (It’s Not Easy)” casts the Man of Steel as rejecting his role of hero.

Ironically, “Superman” has struck a chord in the revival of the American spirit post-Sept. 11. That cultural wave is sweeping Ondrasik to his first real success at age 33.

Radio airplay for the song picked up dramatically in the weeks after the attacks, and Ondrasik found himself onstage at the Oct. 20 “Concert for New York City” at Madison Square Garden--a situation he couldn’t have conjured even when as a teen he dreamed of being like Billy Joel, with 20,000 people singing along to his songs.

“I walked out to the piano and people were holding pictures [of deceased loved ones],” he says, sitting in his tour bus before the El Rey show, a cable news channel tuned in on a TV overhead. “Backstage, big burly men, union guys, were crying. Moms were walking around with kids who now have no dads meeting the Backstreet Boys.”

With his Slovak heritage and down-to-earth demeanor making him resemble a leaner version of actor John C. Reilly, Ondrasik could easily have been mistaken for one of the firefighters at the event rather than an artist in the company of his own heroes such as Joel, Elton John, John Mellencamp, the Who and Paul McCartney.

“I was holding my arm around Pete Townshend for ‘Let It Be,”’ he says in amazement.

With the boost from that exposure, “Superman” is a bona fide hit, and the album, a full 14 months after its release, has sold more than 360,000 copies, with more than two-thirds of that coming since the beginning of September. Ondrasik readily acknowledges that the recent sales boost comes in large measure from a mistaken impression of his song. It’s a situation akin to Bruce Springsteen’s biting “Born in the U.S.A.” being taken by some as a jingoistic celebration of flag and country.

Unlike Springsteen, though, Ondrasik is willing to let the misinterpretations stand.

“We’ve seen everyday people we run into at the supermarket doing superhuman feats,” he says. “That doesn’t really fit the lyrics. But that’s not important.” What is important, he says, is that people are looking to songs for inspiration.

“It’s very rewarding that ‘Superman’ has been able to comfort people and pay tribute to people,” he says. “But lost in all this is that ‘Superman’ had comforting qualities before Sept. 11. Even now, 75% of the e-mails I get are not about [the tragedies], whether it’s a 12-year-old girl who says, ‘I’m the most unpopular girl at school’ or a surgeon having a crisis of confidence after a bad day. No. 1 for an artist is to have an effect, whether the ‘Concert for New York’ and e-mails from policemen or just people across the country. The other stuff is small.”

The small stuff, he says, includes the tragic fluke of timing that has made him an “overnight success” after years of struggle, and the real possibility that “Superman’s” association with Sept. 11 could overshadow everything else to come in his career.

On the first matter, the fact is that the success of “Superman” was building months before the attacks. With its Billy-Joel-meets-Dave-Matthews tone, it was becoming a favorite on adult alternative radio stations, and the video was being featured regularly on VH1, which designated it an “Inside Track” buzz clip.

“We really believed since the beginning of the year that it would eventually be a hit,” says Will Botwin, Columbia Records’ executive vice president and general manager. “We just knew it would take some time to happen.”

For Ondrasik, it just meant more time on what had already been a long haul. He had started shopping demo tapes while he was still earning a bachelor’s in applied mathematics from UCLA in the late ‘80s. In 1996, he finally landed a record deal with EMI and recorded an album co-produced by the company’s president, Davitt Sigerson (whose production credits include Tori Amos and the Bangles). But just one month after the release of the album, “Message for Albert,” the company folded. So out he went into a pop music world increasingly inhospitable to an unknown singer-songwriter, with manufactured teen stars dominating on one end and anger management candidates on the other. But in early 2000, Ondrasik, who’s essentially a solo artist recording under the band name Five for Fighting, caught the attention of Aware Records, a Chicago label that, in partnership with Columbia, was having great success with the band Train, an act with similar qualities. Although it was a tough time for earnest singer-songwriters, executives at the big company latched onto Ondrasik and made a commitment to support his new work, “American Town,” as an extended development project, even as it met with little success initially.

“We want to develop him into someone you can really hang your hat on,” says Botwin. “It’s been a labor of love and a lot of hard work, but we believe he’s really good. He’s worked really hard, and people just like him.”

Ondrasik found similar favor in the offices of VH1, particularly with Rick Krim, the channel’s executive vice president of talent and music programming, who had worked with Ondrasik’s wife, Carla, in the mid-’90s when she was an executive at EMI Music publishing. It was Krim who was told about an e-mail to the singer from a paramedic and arranged a spot for Ondrasik in the New York concert.

“I felt even before Sept. 11 that music was headed in more of a song direction and less fad-oriented,” Krim says.

“People were listening to lyrics, and a strong message could connect more.”

Ondrasik clearly is connecting with an audience, and not just with the single. It’s not quite 20,000 fans a la his Billy Joel dream, but he’s seeing more and more people at his shows--including many of the 1,000 or so at the sold-out El Rey concert--already familiar with material that hasn’t even been on the radio.

“Only in the last couple of weeks, I’ll play ‘Love Song’ by myself at the piano and hear 1,000 people singing, and I almost cry,” he says. “I’ve wanted that for so long.”

*

Five for Fighting appears at the KIIS-FM Jingle Ball, Dec. 19 at Staples Center, 1111 S. Figueroa St., L.A., 7 p.m. $35-$100. (213) 742-7300.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.