T-Cell Transplant Aids Cancer Fight

- Share via

A new, experimental approach to treating tumors--transfusing blood cells from a patient’s sibling--can reverse the spread of kidney cancer, researchers report.

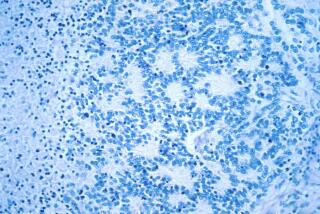

The cancer killers are T-cells, the roving attack dogs of the immune system. When they work, they usually go after the body but do even worse damage to tumors, according to the study appearing in Thursday’s New England Journal of Medicine.

“This is the biggest advance in kidney cancer in my research career--in my almost 22 years of doing kidney cancer research,” said Dr. Nicholas Vogelzang of the University of Chicago, a medical advisor for the Kidney Cancer Assn.

However, the authors at the National Institutes of Health cautioned that the approach is still being studied and is itself dangerous.

Transfusions have been used for decades to treat leukemia and other blood cancers. But this is their first use against solid cancers.

Vogelzang said Chicago is among at least 10 institutions testing the approach described in the study by Dr. Richard Childs of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

Childs and researchers at the National Cancer Institute are preparing tests against 15 other cancers, including those of the lung, breast, prostate and esophagus.

“The only way we’re going to know if it works is trials. Animal trials have not been particularly helpful,” Childs said.

The study describes the first 19 people to get transfusions to treat cancer that had spread from the kidney. Tumors disappeared completely in three and shrank to half their former size in seven others.

Only two of those seven had a later relapse, and one of them improved again after additional treatment with a different immune therapy.

The patients got transfusions of both stem cells, the immature cells which develop into various kinds of blood cells, and T-cells.

It was the T-cells that destroyed tumors, Childs said.

No patient has been followed for more than about 2 1/2 years. Once cancer has been in remission for five years, doctors believe there is a reasonable chance of remaining cancer-free.

The approach should stay experimental for now and will be nowhere near a cure-all, even if more studies and longer follow-up show that it should be an accepted treatment, Childs said.

Two of 19 patients died of the treatment itself, and the T-cells took months to work.

Four months after John Sirmans’ transplant, his tumors were still growing. A CAT scan of his lungs “looked like golf balls in a sock,” said Sirmans, of Dayton, Ohio.

That was in December. He thought that Christmas would be his last. “Then 30 days later, I came back and these things were shrinking like crazy.”

Childs’ article lists Sirmans as a patient whose tumors had shrunk at least by half. He has been cancer-free since summer.

About 30,000 new cases of kidney cancer are found each year in the United States. If it is caught before it spreads, removing the kidney may cure the patient. But in about 11,000, it is out of the kidney before it is found. Then it moves swiftly, often killing within a year.

“I would guess only about 20% would have slow-enough growing tumors that this would even be an option,” said Dr. Robert Figlin of UCLA, also a KCA advisor.

Vogelzang disagreed. He said the approach could be considered not only for the 25% who have an average survival time of 20 months but also for the 53% whose average life span is 10 months from the time new tumors show up.

Another problem is finding a donor. There’s only a 1-in-4 chance that a brother’s or sister’s blood will be a good enough match for the patient’s. The donor also must be healthy.

Since Childs’ study is so small (he has now done 33 transplants, with 15 patients improved and more time needed to evaluate four), it could be a fluke that about half got better.

Side effects are major. All but two patients whose tumors improved had rashes or diarrhea and gut pain from graft-versus-host disease.

The new T-cells killed one patient. A second died of an infection resulting from the transplant. Figlin called the death rate unacceptable.

Childs has tried T-cell transfusions on eight people with skin cancer. None responded. However, he said he does not know whether that is because it does not work at all or because the patients’ cancer spread too fast to let the T-cells get to work.